Contents

Contents

Introduction

At the approach of the eighteenth century the great plain lands along the coast, a vast and resourceful empire, many times larger than England, had become somewhat subdued and disciplined into the pattern of civilization. It was settled sparsely and irregularly, but much of its fertile soil was under cultivation; roads were creeping from settlement to settlement, and packet ships were beginning to link the seaport towns and villages. It was an empire preponderantly agricultural; an empire largely self-sustaining, although dependent upon Europe for its luxuries and refinements; yet an empire almost entirely unconscious of its unity. It was still a collection of individual colonies and communities with few bonds in common; still provincial and limited in its vision by the horizon of local boundaries.

Its western borders were nibbling into the great band of forest that swept from the St. Lawrence to the Gulf. They were creeping toward the slopes of the Blue Ridge; up the Hudson and Mohawk valleys; through the foothills of the White and Green Mountains, and into the Berkshire Hills. It was a far-flung line of advance, headed by traders and trappers, and backed by hundreds of landless pioneers, all fighting their way into the Indian country steadily and irresistibly. In the century stretching from 1675 to 1775 this advance was to gather momentum until, upon the eve of the Revolution, the more daring of the vanguard had penetrated into the Mississippi basin. Behind them the mountain ranges, the foothills, and the upland regions were dotted with widely scattered settlements and clearings.

The character of the life on this frontier changed but little during the century; for it was necessarily an arduous and comfortless existence, tempting none but the hardy and adventurous and those pressed by necessity. On the other hand, as the century passed, life in the older settlements underwent a marked change, until, with the advent of the Revolution, the gulf between the town dweller and the frontiersman had widened to the point where they seemed the product of two widely different types of civilization.

A gradual and far-reaching economic development was ordering the life and structure of the older communities along the seaboard into a new design. The areas of the coastal plain, as it became more thickly covered with plantations and the yielding acres of the freeholding farmers, poured out yearly a great stream of provisions, much too large to be consumed at home. Tobacco from Virginia and the South; corn, flour, furs, hides, flax, and hemp from the middle colonies; lumber, turpentine, fish, and live stock, found their way down to the seaport towns to be sent to England and the Continent, to the West Indies, or to the other colonies. In return came money and credit and all the rich and costly things for the home or person the older civilization could supply. In addition, wealth poured in from the many young and flourishing industries that had sprung up in the middle and northern provinces – the manufacture of linen and woolen materials, felt hats, stockings, bar iron, candles, paper, and rope. In New England, where by the middle of the eighteenth century seventy ships were being launched annually, fortunes were being accumulated, and whole communities were made prosperous by the foreign and coastal trade and by the fishing carried on in New England bottoms. Under the stimulus of this prosperity, villages grew into towns, towns into cities. In 1700 Philadelphia was a tiny town of a few hundred houses; Charleston was still smaller. New York had barely five thousand inhabitants, while Boston, the largest community in the colonies, perhaps seven thousand. Seventy-five years later these centers had grown into flourishing cities, the equal of any save the very largest and greatest of the European cities in population, wealth, and culture.

Coincident with their growth and wealth came the forging of a society actuated by the manners and aims of European aristocracy, a society that attempted to reproduce the formulae current in the cultured circles of England and the Continent. Much of the simplicity and ruggedness of the early days was passing and a type of town life was coming into being, clearly marking it apart from the agrarian society of the hinterland. Unless the simple life of the frontier and the more ordered existence of the town are fitted into one picture, it is impossible to comprehend – rightly the variety and contrast of early American life. Judging from special evidence, it is only too easy to. visualize these colonists either as rude and graceless folk battling in a bare and grim environment for the necessaries of life, or, as formal figures moving in an elegant and artificial society, a near replica of the courts and fashionable circles of the Old World. The truth is it was as curious a blend of both sophisticated civilization and primitive life as can be found in all history.

It is during this century of expansion that the materials for the study of costume begin to accumulate in a constantly increasing store. In the previous era of the early settlements the evidence is discouragingly scanty. The pictorial records – they are the most valuable of all records in this study – are few, and the information to be gleaned from letters, diaries, books, invoices, and acts of legislation is not too abundant. Many of the conclusions respecting the early costume must be drawn from inference and deduction, and from knowledge of European sources.

As the colonies won to some measure of wealth and leisure, materials became richer and more varied. The first newspaper was published in 1690, and, although short lived, others followed, and from their quaintly worded advertisements it is possible to check quite accurately the arrival of new fashions, and to trace the growth of native manufactures. The monthly journals appearing toward the middle of the century also contained occasional bits of information; but on the whole they are much less valuable sources than the weekly newspaper. European travelers in the colonies were fairly numerous, and, fortunately for us, many of them were observant men who published their impressions. These travel accounts, like those of the Abbé Robin, Burnaby, and Chastellux, are packed with comment on the life, manners, and dress of the time. They are doubly valuable, since they constantly, measure this life by European standards. Then there exists a wealth of documentary evidence in the form of letters, sermons, court records, diaries, bills of lading, handbills, and account-books.

There is a corresponding increase in graphic material. Toward the middle of the eighteenth century, engravings and wood blocks appeared in numbers in the papers and journals, on handbills and stickers. The technique of these early illustrations is usually crude, and the facts they present are sometimes misleading, owing to the indifferent skill of the artist; yet they furnish many valuable clues for the student of costume. It is to the painters of the period, however, that the greatest debt must be paid.

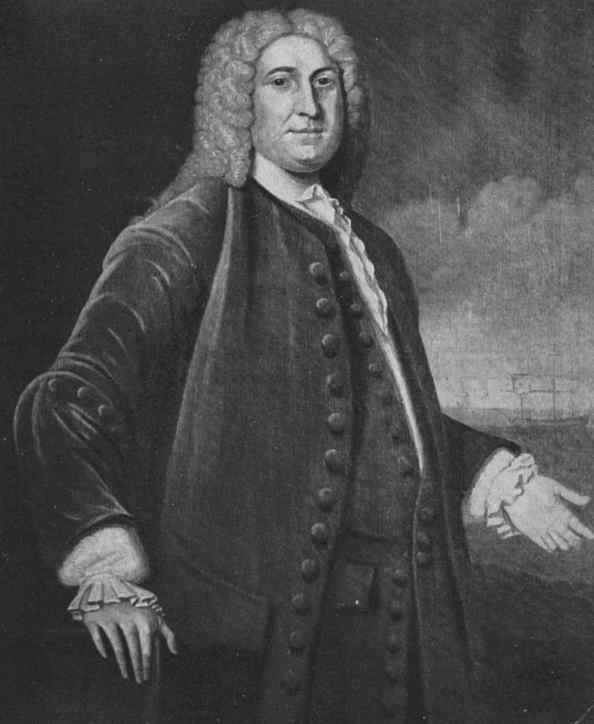

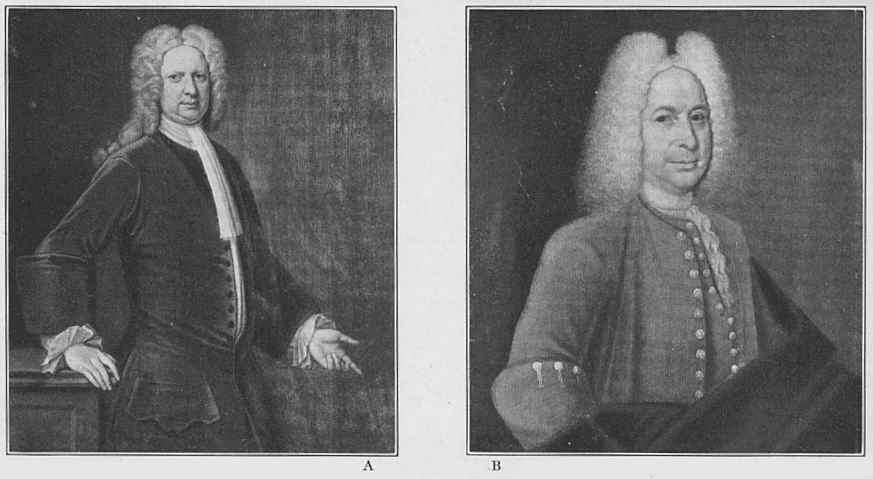

Almost all the early American painters were portraitists. This was necessarily so, since not only did the pictorial expression of the time in western Europe find its chief outlet in the portrait, but in the dissenting, protestant atmosphere of the new country only an art holding some flavor of the utilitarian could flourish. These early American painters are obscure, most of their canvases being unsigned and little being known of their lives. They were mostly men of small talent and of little training. Their efforts were usually constrained and halting, though sometimes they achieved a kind of compelling naïveté often found in primitive work.

In New England one first encounters the names of painters of whom almost nothing is known – Joseph Allen, Thomas Child, Lawrence Brown. Later appeared men of greater attainment – Badger, Blackburn, Smibert, and, most gifted of all, Robert Feke of Newport. In the South, likewise, many of the early portraits are unattributed. From Charleston comes one name, that of Henrietta Johnson, a worker in pastel during the early years of the eighteenth century. By 1711 a Swedish painter, Gustavus Hesselius, appeared in Delaware and Maryland. In New York the Duykinck family and Gerret van Randst were at work; and the Philadelphia botanist Christopher Witt painted a few portraits. Later in the century Charleston attracted a little group of artists – Jeremiah Theuss, B. Roberts, and Alexander Gordon. An English painter, Charles Bridges, worked in Virginia from about 1730 to 1750. Year by year from now on the number of painters and the quality of their efforts increased, until by the end of the colonial era the four greatest of the early American painters were at work – namely, John Singleton Copley, Benjamin West, Charles Wilson Peale, and Gilbert Stuart.

The work of these men and their colleagues, both native and foreign, affords a rich treasury of material. It is costume material in its most usable aid accessible form; but it is not without errors and pitfalls for those accepting its facts at their face value. Among both the early and the later portraits there are many inaccuracies in the dates assigned them, even among those hanging in important museums. There are instances of pictures being dated almost a hundred years before the costume depicted could possibly have appeared. On the other hand, there are examples of costumes portrayed which were fashionable several generations before the date of the picture. This is sometimes a mistaken dating, or it may simply be additional proof that certain conservative persons clung to to the fashions of an earlier day. There are many examples of portraits being attributed to the wrong artist. Other pictures have been changed and retouched, and there are a certain number of modern paintings masquerading as original colonial canvases.

In the work of the early portraitists it is not uncommon to find the use of certain stock poses. Not only do numbers of pictures exist in which the pose is precisely the same, but the same dress is sometimes used (Plates 50, LI). Only the head, and sometimes the hands, differentiate these portraits. It was the habit of certain of these painters, once having hit upon a number of happy poses, and having copied a number of particularly fetching gowns, to spend long winter months painting copies of them, omitting only the head and perhaps the hands. In the late spring, when the sun had again rendered the roads passable, they loaded these partially completed canvases upon carriages and pack-horses, making a circuit through the rich farming districts. Thus many a simple farm-wife sat while the artist painted her head into the vacant space on one of his canvases, she acquiring a portrait of herself bedecked in a gown worthy of the governor’s lady. There came into being whole series of these portraits, in which a great variety of sitters attempted the same formal gestures and stared out self-consciously from above the same marvel of dressmaking.

Another custom among colonial painters, more particularly among the later ones, was the use of draperies over parts of the figure in an evident effort to achieve a look of elegance and luxury. Often the effort is quite apparent; but sometimes it is difficult to separate the legitimate costume from the studio accessory. Of course, this practice occurs usually in the portraits of women.

Always to be considered and allowed for is the artistic personality of the painter; the range and limitation of his interests, his technical command, his race and background. A technically awkward painter may make the most graceful of sitters and the richest of costumes seem inept, frigid, lifeless. On the other hand, certain suave technicians contrived to lend an air of graciousness and sophistication to the stiffest, most unbending of subjects. Then, too, almost always the race of the painter strikes through. Certain of the Dutch painters of early New York have given a Low Country air to all of their sitters, regardless of their ancestry. Balancing this, many English artists have converted some excellent Dutchmen into Englishmen on their canvases. With this transfer of nationality, practised unconsciously by artists, goes an accompanying change in the character of the sitter’s dress. These changes are slight but none the less real. They involve no actual alteration in the garments worn, only a difference in the way they were handled and draped to the figure. They emphasize the fact that national characteristics of dress are often less a matter of the actual kind of clothing worn than the air and manner in which a dress is worn.

In the main the painters in the colonies worked in the English tradition and reported the appearance of things in the English fashion. This was as it should be; for always the dress of colonial days was predominantly English. Even in the foreign communities, as among the Dutch in New York, the Germans in Pennsylvania, the Swiss of New Berne, the tendency was to discard the habits and habiliments of their home country and to acquire the ways of the new land. England herself, when she borrowed from the modes of France, Spain, Germany, or the Low Countries, never accepted them in their entirety. In costume, as in art and manners and all other things, nothing passed through English hands and minds without becoming transformed in the passing; for England always possessed that stubborn power of converting her borrowings into something distinctly and unmistakably English. Something of that stubborn power found its way across the Atlantic and operated during the early years of the colonies.

I. COSTUME OF THE MEN 1675-1775

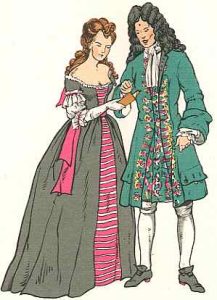

About the year 1670 one finds a change in the costume of the man throughout western Europe, England, and America. This change marked the separation of the fanciful costume of the Old World from “the triarchy of coat, waistcoat and breeches” of the New, which in one form or another has lasted until the present day.

BODY GARMENTS. – The coat is usually claimed to have been developed from the “Eastern fashion of vest… after the Persian mode,” as mentioned in Evelyn’s Diary in the year 1666. In relation to this, Kelly and Schwabe state: “The peculiar costume known as a vest after the Persian fashion, adopted in October 1666 by Charles II and his court, was an ephemeral mode and had little or no lasting influence. It was introduced as a counterblast to the craze for French fashions, which after as before retained their supremacy. We have been unable to identify it in contemporary art.” For the best information concerning this new fashion in vests that made their appearance in Charles II’s court, turn to the October entries in the Diaries of Evelyn, Pepys, and Rugge for the year 1666. It is interesting to find them all giving identically the same information relative to the king and the court adopting the new dress which all refer to as the “Eastern fashion in vests.”

To quote from one of the above; Evelyn makes an entry in his Diary under date of October 18, 1666, reading as follows:

“To Court. It being the first time his Majesty put himself solemnly into the Eastern fashion of vest, changing doublet, stiff collar, bands and cloak, into a comely dress, after the Persian mode, with girdles or straps, and shoestrings and garters into buckles, of which some were set with precious stones, resolving never to alter it, and to leave the French mode, which had hitherto obtained to our great expense and reproach. Upon which, divers courtiers and gentlemen gave his Majesty gold by way of wager that he would not persist in this resolution.”

It appears, therefore, that the fashion for “Persian vests in the Eastern fashion” was more or less limited to court circles abroad, and was of such a short vogue they could hardly have appeared in America. They can be dismissed without further comment.

What seems to have been more probable is that the coat in this style and cut, appearing about 1670, was developed from a garment then called a cassock (Fig. 42). The cassock, in turn, had been derived from the earlier military garment, the leather jerkin with long skirts (Fig. 35 B). An authority states: “It is collarless, reaches to the knee, and has full turned up sleeves.” In support of this, Planché defines the cassock as “a long loose coat or vest.” In referring to an illustration of Fairholt’s of a hackney coachman, taken from a broadside of the time of Charles I now in the British Museum, and called by Fairholt a cassock, Planché adds: “…which is certainly nothing more or less than a loose coat, with buttons all down the front, and large cuffs, the prototype of the coats of our great grandfathers.” Mr. Bolton states: There seems to be no evidence that fashion was slow in reaching America, nor that fashion originated on this side of the ocean. The Colonists visited England so often that we may assume a Virginia gentleman would not be content with a coat out of fashion in London.

He further states that “The only difference appears to be where we seem to have had a short period of local conditions of costume not obtaining in England.” This is likewise true of the gentlemen of New England and the central colonies, particularly in the circles surrounding the governors. In further relation to this following of the English fashions, Mrs. Earle states:

“Around the governors of the various provinces gathered in each capital, a little circle of card playing, horse racing, fox hunting court attendants, who naturally wore the best dress in the provinces; English younger sons, sent to America to sober down, where they proceeded to liven America up. The constant correspondence of the governor and his officials with England kept this circle fully informed upon all the changes in dress; and many of these letters, both private and official, have been preserved. From them, we gain an excellent notion of the importance of good dress, and the prevalence of good dress in the colonies, and of good living in every respect – furniture, wine, food.”

It appears, therefore, accepting the above as a basis, that shortly after the coat and vest became the fashionable garments in England in 1670 they also featured in the wardrobe of the colonial gentlemen in America. Thus, one finds the first coats following the lines of the cassock, cut straight and without being shaped in at the waist, and extending to about mid-thigh, or a little beyond (Fig. 43 A). They were provided with buttons and buttonholes down the front; but as a rule they were only fastened together to about the waistline. From there down they remained open. At the elbow, either a little above or below, are found the broad turned-back split cuffs, usually of a different material from the coat. Below the broad cuffs one finds the full sleeves of the skirt. They are gathered to a band, at the wrist from which the ruffles fall over the hand.

The pockets were usually horizontal, placed low down and covered with large flaps. The vest was exposed when the coat was open, and reached to a little below the waist-line.

The next change to be noticed in the coat was shortly after 1670, when it began to be cut a trifle more full in the skirt and commenced to be more and more shaped in at the waist (Plates 17, 20, 25, 26, etc. Fig. 43 B). It was also gradually lengthened until it reached to the knees, or a trifle below. The vest also followed along the same lines, gradually lengthening until it was only a few inches shorter than the coat. The vest was provided with buttons and fastened most of the way down. The fashionable way to wear the coat at this time was to allow it to remain open. In the back the full skirts were split in two openings, one at each hip. The openings were provided with buttons and buttonholes, so it could be closed if desired. The pockets were still set very low in the coat and vest and were either provided with large flaps or edged with braid or galloon. It was in these great pockets the men carried, their snuff-boxes, lace handkerchiefs, and silver combs, the latter used to comb and dress the great periwigs. The horizontal pocket seems to have been more generally preferred than the vertical ones. While sleeves of elbow length occur throughout the century, there was a tendency for the sleeve to lengthen until, by the last decade of the century, it was quite general for the sleeves with their turned-back cuffs to almost reach the wrists. Both vests and coats were collarless.

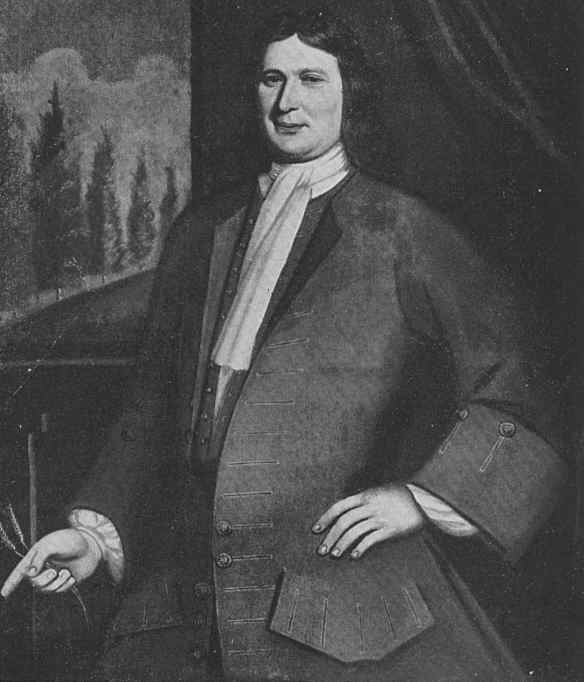

Many men preferred wearing the coat without the vest (Plates 19, 24 A. Fig. 44 A), which, in a way, became a fashion, especially among the younger men, and lasted into the early years of the eighteenth century. The laying aside of these heavy vests must have been a great comfort in the summer months, especially in the South. The coats were allowed to remain open, and the full linen shirt hung over the waist-band of the breeches. As a matter of fact, the coats never seem to have been fastened, the buttons and buttonholes being more for adornment than for utility. The buttonholes “were carefully cut and laid around in gay colors,” we are told, “embroidered with silver and gold thread, bound with vellum, with kid, with velvet.”

At the beginning of the last quarter of the seventeenth century the coat was being more and more fitted to the waist. This fashion increased with the years, until, when the last decade of the century was reached, one finds the skirts of the coat enlarged and stiffened. This resulted in the coat skirts being gathered into pleats that radiated in fan-shaped forms from a button on the hips. As will be seen, this style of enlarged skirts, gathered into radiating pleats in the back, lasted until about 1750, when it gradually went out of fashion. These buttons, by now more or less ornamental, were copied from the buttons worn on riding-coats, the coat-tails being buttoned to them, thus keeping them out of the way when the rider mounted his horse. One also reads that “they were used for looping back the skirts of the coat.” It is said “that loops of cord were placed at the corners of the said skirts.” This must have been convenient for everyday wear and for walking as well as riding.

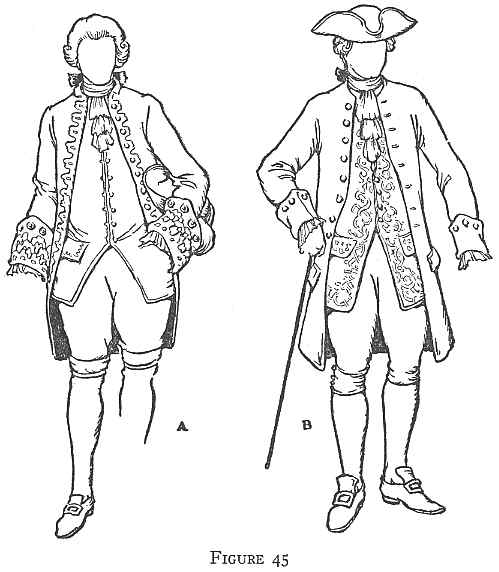

During the first half of the eighteenth century there is no marked change in the style of the coat, except in the narrow turned-down collars occasionally appearing on coats in the late thirties (Fig. 45 A). Other changes occurring during these years were concerned with minor details. The features already explained in the costume of the fashionably dressed man became more and more pronounced. The fashionable coat and vest from 1700 to 1750 remained about the same length (Plate 18, Fig. 44 B), the coat extending to the knees or a little below, the vest remaining several inches shorter than the coat. As a general rule, neither the coat nor the vest was provided with a collar. Between the years 1715 and 1720 the coats with the full skirts gathered into radiating fan-shaped pleats from the hip buttons were further emphasized by stiffening the skirts of both the coat and vest with buckram to give them “a lamp shade outline as if to rival the ladies’ hoops.”

From the beginning of the century the general tendency was for sleeves to lengthen toward the wrists, where they were turned back in deep split cuffs. The cuffs were usually held in place by buttons. Heath says: “The cuff of the George the First coat had three buttons with three notched holes, otherwise there was no ornamentation, and the material was as plain and economical as decency permitted.”

It was during these years that the pockets of both the coat and vest were raised considerably higher. We are told that “the opening of the pockets was much reduced and sank to about the point at which a man could easily put his hands into them,, as if the very tailors felt the movement in favor of thrift, and the pleasure of clutching one’s money.”

Many of the waistcoats were richly ornamented down the front and around the skirts with embroidery in the form of running vines interspersed with clusters of flowers. The great pocket flaps were likewise richly embellished; also around the buttonholes. Buttons were selected with great care. They were made of paste, “were rich in colored enamels and jewels, in odd natural stones of lovely tints, such as agates, carnelians, bloodstones, spar, marcasite, onyx, chalcedony, lapis lazuli, malachite.”

Between the years 1750 and 1760 the buckramed skirts of the vests and coats gradually lessened in width and exaggeration, until they finally went out of fashion. Fairly plain and closer-fitting skirts to the coats took their place. Horace Walpole is quoted as saying,: “…the habits of the time shrunk to awkward coats and waistcoats” (Fig. 45 A B). The coat, which in the beginning came together in the front (Fig. 43 A), was gradually left more and more open, until one finds it sloping away from the neck toward the waist, thus decidedly increasing the opening (Plate 29. Fig. 45 A B). There was still, however, a trifle of fullness left in the skirts. “Fashion,” it is said, “was getting rid of lace and embroidery, and all unnecessary waste material. Instead of the quadruple skirts with multitudinous folds, which were the delight of the days of William and Mary and Anne, a man’s coat tails were now reduced almost to the dimensions of the modern frock coat. To save appearances, however, the numerous folds were represented by three petty ones, which hung at each side of the skirts apparently suspended from a button.”

The large turned-back cuffs (Plate 29, Fig. 45 A), that by now reached the wrists, with only a slight ruffle of lace showing from under them, were worn until about 1760. Gradually the smaller cuff was coming into favor and after that date became small and tight (Plate 36, Fig. 45 B).

It was also about this time, 1750 to 1760, that the great pocket flaps were much reduced in size.

The vest was left unbuttoned a short way down the neck, in order to show the carefully arranged cravat. It was then buttoned up to about the waist-line. From this point the skirts sloped away rapidly toward the sides. The vest was considerably shortened, the skirts coming to about mid-thigh (Plates 29, 30, 31, Fig. 45 A B). Thus one sees the coat and vest gradually “shrinking” into smaller garments which lasted until the Revolution.

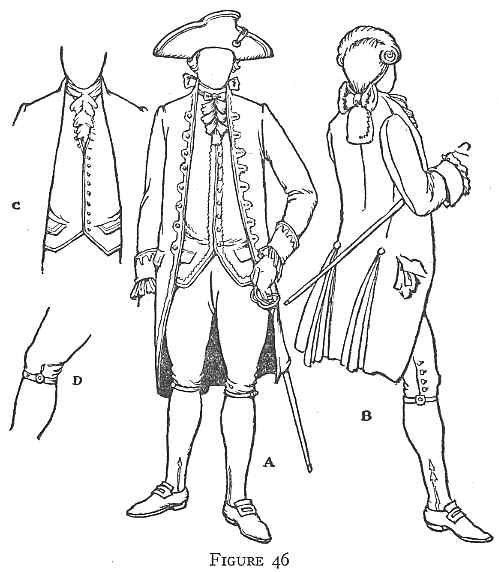

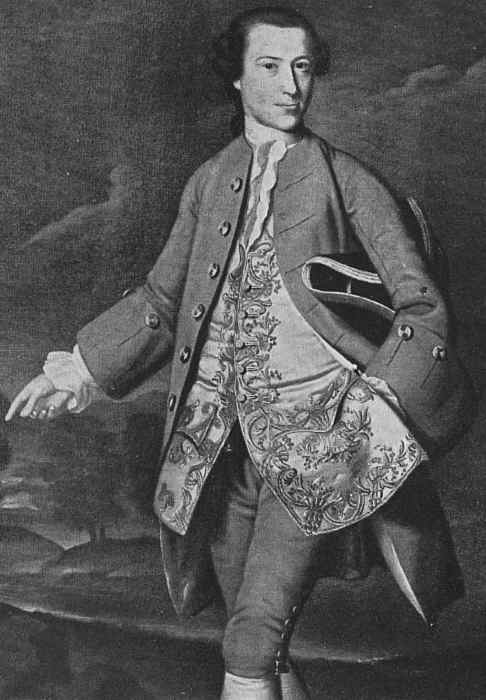

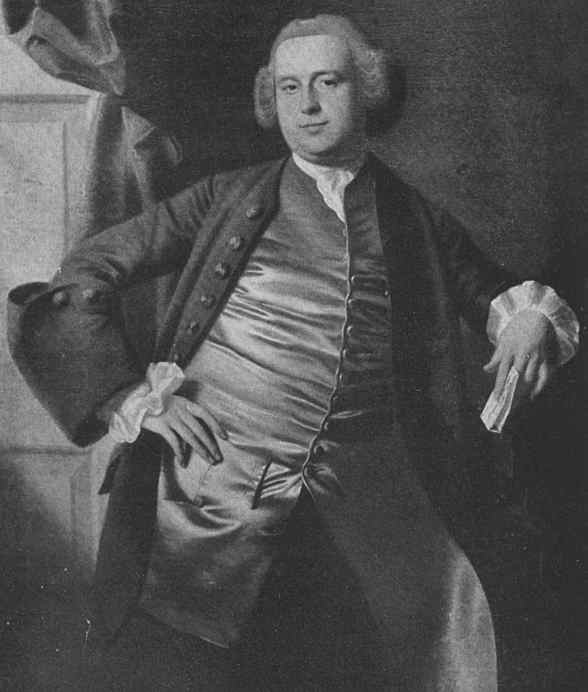

The illustrations (Plates 36, 37, 38, Fig. 46 A) depict a man’s costume as worn on the eve of the Revolution. The coat has lost most of the fullness and amplitude characterizing it up until a little past the middle of the century. The front of the coat drops away in straight but slightly slanting lines to about the knees. The coat-tails still radiate with a few folds from the two buttons that have been moved more to the back (Fig. 46 B). The cuffs are much smaller, and they may or may not have the buttons on the upper edge. The waistcoat is considerably shortened. It buttons in a straight line to a little below the waistband of the breeches, where it slants off at a decided angle, forming a short skirt (Plates 37, 38. Fig. 46 A C).

BANYANS. – It can scarcely be said that the dress of these years of which we are speaking, picturesque and charming as it was, was altogether comfortable. The long tight-fitting vests, the heavy and excessively hot wigs, the greatcoats with large turned-back cuffs, ruffles of lace at the wrists and neck, did not provide a dress conducive to comfort and lounging. Without doubt, the coat, the wig, and sometimes the vest, were taken off and laid aside as soon as the man came into the privacy of his own home, he donning a more comfortable garment. Not only was this négligé needed for lounging, but it should not be forgotten that the long summer months of exceedingly hot weather must have made wigs and coats, especially in the South, almost unbearable. Men undoubtedly went about in linen shirt and breeches; or wearing over the shirt merely a vest. To fill this need, then, for a more comfortable garment that could be worn as a négligé, there was introduced a gown called either a “morning gown,” or a “night gown.” This garment, in America often termed a night gown, did not refer to a sleeping garment, but was a loose, comfortable robe worn as a dressing-gown, or négligé. The sleeping garment, when one was worn, was usually known as a “night rail.” It is of interest to find that this morning gown, or dressing-robe, was just as popular in many of the countries of Europe as it was in America. This was especially true of both England and France. It appears that early in the eighteenth century a new garment similar in cut and form came from England and was known as a “banyan.” It became exceedingly popular with the colonists, particularly in Philadelphia and the South, the summers being hot, and in some sections almost tropical. It was a handsome article of dress, and, for those who could afford the expense, made out of the richest silks, brocades, velvets, and other fine materials. Mrs. Earle states: “By the year 1730 certainly, and possibly earlier, these Indian gowns had become known generally by the name banyan, banjan, or banian.” Nor were all banyans made of silks or damasks; for there were many who could not afford such rich materials, or wanted a less expensive garment for general wear. They could be procured, therefore, in cheaper materials, such as striped and figured cottons, though they would probably be lined with colorful materials.

The banyan made of brocade or velvet and provided with a heavy, warm lining was for winter wear. For summer, there were banyans of “soft Chinese silk” unlined. What a welcome relief these cool, loose garments must have been, after the heavy coats with their deep turned-back cuffs and stiffened skirts! Banyans were worn alike by men, women, and children. Not only were they worn as a house gown, but during the summer months merchants and lawyers went to their counting-houses and offices so attired. In the South the masters and overseers of the plantations went the rounds of their vast estates garbed in these cool and comfortable garments.

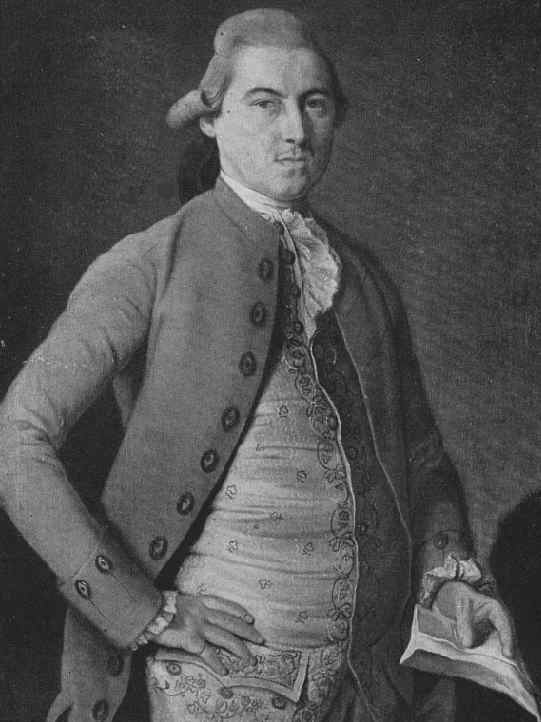

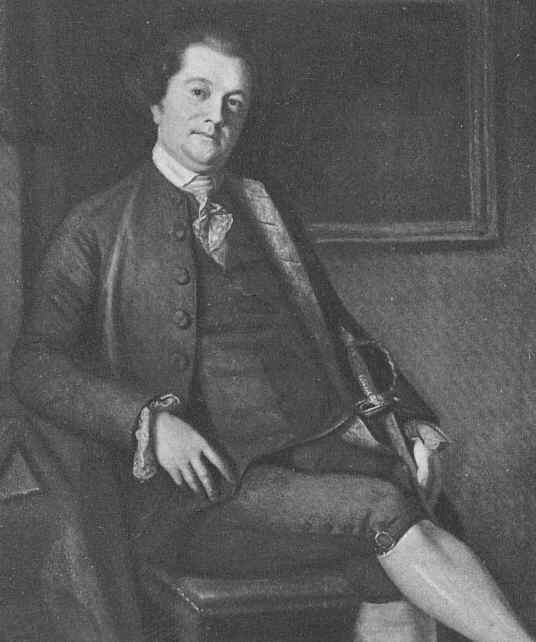

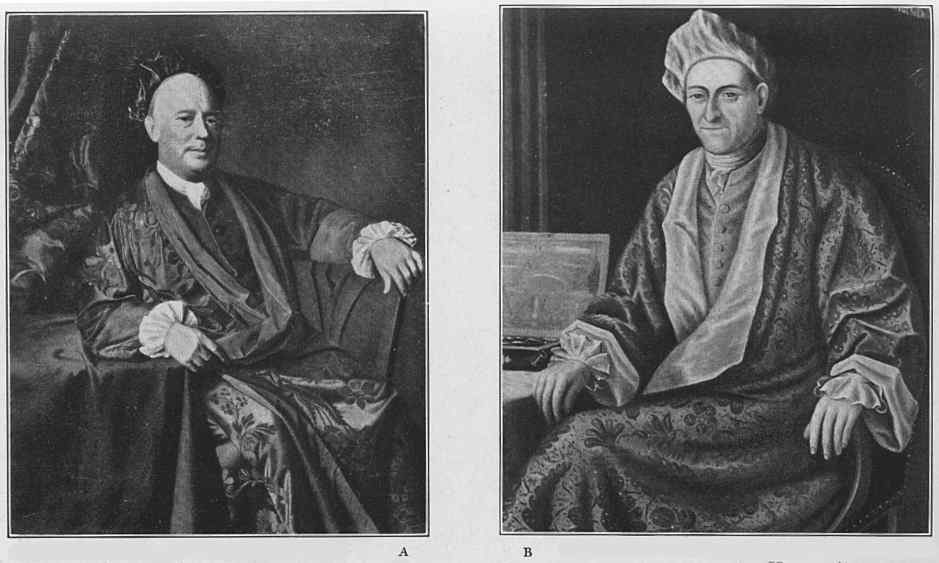

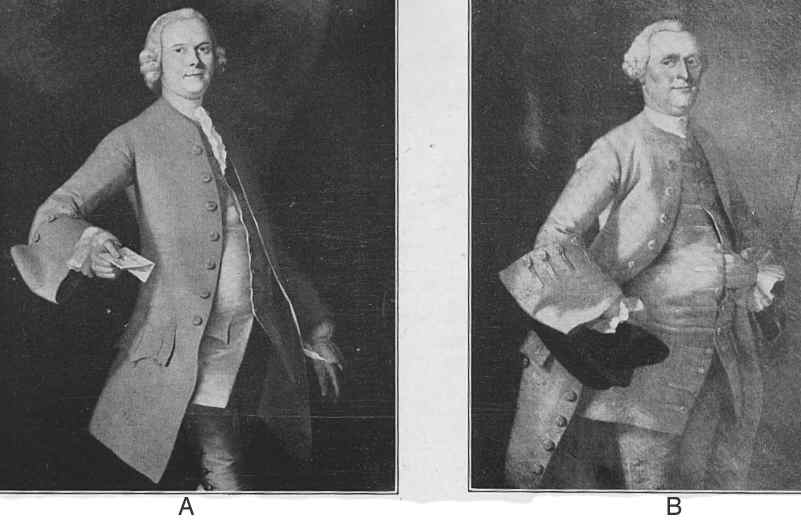

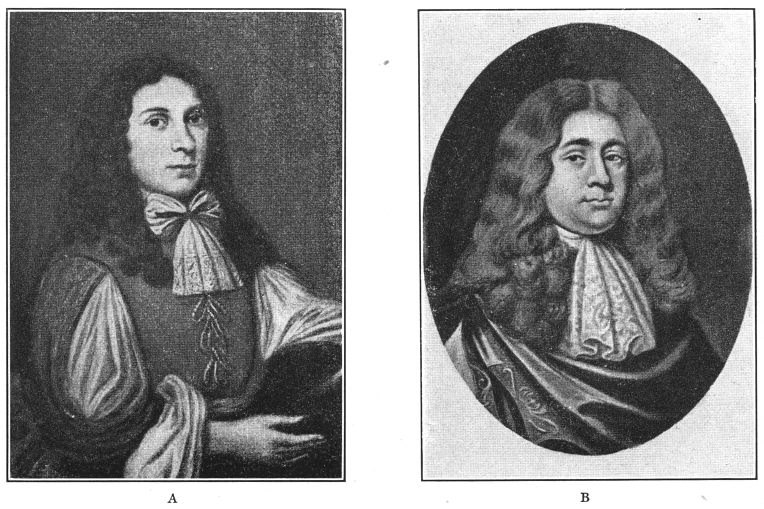

As can be seen in the portraits of Joseph Sherburne and Ezekiel Hersey (Plate 33) and Nicholas and Thomas Boylston (Plate 34), banyans were an important enough garment to have been worn by them while having their portraits painted. In both instances they are made of rich figured silks, with a lining of plain silk. The plain silk of the lining, as a rule, formed the long, rolling kimono-like collar, as well as the full turned-back cuffs of the fairly ample sleeves. The banyans were made the same inside and out and thus were often worn reversed. With the banyan is usually associated the turbanlike head-dress that was worn over the-shaved head on the removal of the wig. (See Turbans under the caption HEAD-GEAR)

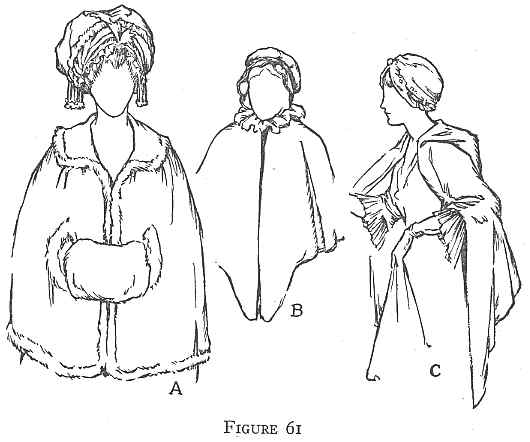

CLOAKS AND OVERCOATS. – From the beginning of the period, capes and cloaks were no longer fashionable garments, nor of so much importance as in previous times when the wearing of a cloak in the “grand manner” was part of the training of a gentleman. It is true, however, they are met with from time to time during the entire eighteenth century. Especially were they worn in cold weather by travelers, either when mounted on horseback or when traveling as passengers in the great lumbering coaches. In either case, a traveler could bundle himself up to his eyes in a warm, heavily lined cloak. The cloak was now more like a great mantle, worn wrapped around the figure instead of being thrown over the shoulders as formerly.

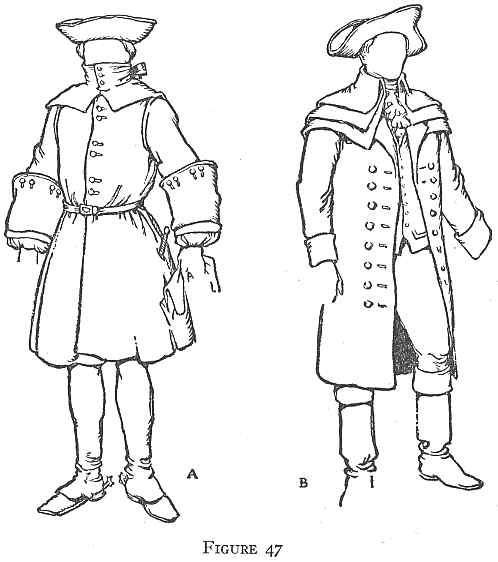

In place of the cloaks, one finds for general wear the long, loose overcoats coming into fashion (Fig. 47 A). They were provided with great cuffs turned back in the same manner as those upon the sleeves of the coat. Around the neck was a fairly large flat collar. Or, the collars overlapping, the outer could be pulled up around the head and face and buttoned down the front, thus giving protection from the cold. They were commonly belted and buckled-in at the waist. Shortly after the middle of the eighteenth century one meets with coats provided with capes (Fig. 47 B). Sometimes a double or triple cape overlapped the shoulders. They were also provided with large revers that turned back in front. The coat was double-breasted.

There is little doubt but that the earlier types of leather and fur coats were still worn, such as “mooseskin,” “raccoon-skin.” Of especial favor among huntsmen were the “deerskin coats.”

BREECHES. – Petticoat-breeches were undoubtedly worn on occasions, in some sections of our country, under the long coats; probably in the South or among the Dutch in New York. Even in these sections they must have gone out of fashion by 1680. The breeches in more general favor throughout the country during the early years of this period were the very “full gathered breeches” of the knickerbocker type, appearing in voluminous folds from under the skirts of the long coats and vests (Fig. 43 A). From these full-gathered breeches were developed breeches of more moderate cut, gathered tighter at the knees (Fig. 44 A B etc.). They seem to have been generally worn by 1675.

The next change came in during the last years of the eighteenth century, when the breeches were made to fit the leg quite close. They were “not tight to the leg, but just full enough for comfort.” They were cut, however, full in the seat, and were gathered to a tight waist-band (Fig 46 A). These tight-fitting breeches came down over the knee and were fastened in place by a buckle (Plate 26, Fig. 46 B D), or fastened up on the outside with small buttons, usually four or five in number (Plates 29, 38). Outside of the buckles and buttons at the knee, these breeches were not otherwise embellished. As a rule, the breeches matched the coat in color and material; though odd breeches of a plain material might have been worn. If so, they were usually of black velvet.

After the close-fitting knee-breeches once came into fashion, there seems to have been very little change in their cut and fit (Plates 28, 29, 30, 35). In fact, so long as the coat and vest retained their full skirts, the breeches were hardly visible (Plates 17, 18, Fig. 43 B ). All these-types of breeches were tailored to fit tight over the leg, were fairly full in the seat, and were gathered up to a closefitting waist-band. At the knee the breeches were brought together and made to fit close, either by a buckle or in a series of buttons. Mrs. Earle states: “Breeches-making in this century [eighteenth] became a trade in itself, aside from tailoring, because the breeches were commonly made of leather, deerskin or sheepskin, requiring different workmen.”

Toward the end of this period with which we are dealing came the introduction of skin-tight riding breeches. These were worn until the end of the century.

LINEN. – Under the coat and vest the shirt was worn. The material from which these shirts were made ranged from finest Holland linen to coarse cotton or calico, according to the position and purse of the wearer. As has been seen, they were often worn without the vest (Plate 19, Fig. 44 A). From under the coat-sleeves appeared “the ruffles of lawn or lace at the wrist.” In the early years of the period considerable of the shirt-sleeve as well as the ruffle appeared from under the great elbow cuffs (Plates 19, 20, 25, Fig. 43 A B); but later the cuff was brought closer to the wrist, the ruffle alone being exposed (Plates 17, 18, 28, 36, Fig. 44 B, Fig. 45 A B).

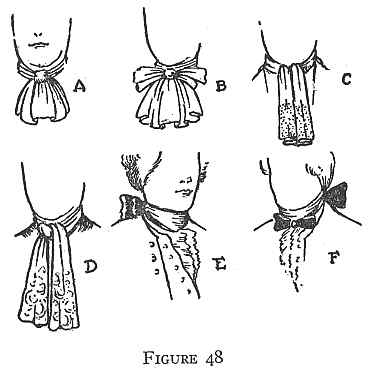

As has been noted, the cravat or neck-cloth was worn contemporaneously with the falling band. (See Chapter II, Section III, on Linen.) It seems to have been introduced into America about the year 1660, gradually supplanting the band in general form. Mrs. Earle mentions that “Governor Berkeley, of Virginia, ordered in 1660 a cravat which was to cost five pounds. Such rich neck wear as that could not have been found in New England at this date.” (See also the portrait of Stephen Winthrop, Plate 13) In the wearing of these first cravats, the neck-cloth passed around the neck and was tied under the chin with “short-spreading ends” (Plate 13 B, Fig. 48 A). Sometimes the ends of the cravat were brought together and fastened at the throat with a ribbon bow (Plate 13 A, Fig. 48 B).

The next change in the cravat took place in the eighties, when the cravat no longer was gathered into the throat by a ribbon tie. The tie was lengthened and fell freely down the front in two long ends, which carried over the neck-band (Plates 17, 14 A. Fig. 48 C); or the ends were simply knotted with a single tie falling down in two straight ends (Plates 15 A, 21, Fig. 48 D). The long cravats worn in this manner were considered fashionable, particularly by the older men, who wore them well into the eighteenth century.

After 1692, the Steinkirk cravat (Fig. 44 A) appeared among the fashionably dressed men in France. It was soon accepted in England, and in both countries was occasionally worn by the women as well. From England, or from France, this fashion was introduced into the colonies, where it was worn by the young bucks and dandies. Here is an interesting example of the way a new style may be brought about. Quoting from Planché: The battle of Steinkerque, 3rd. August 1692, introduced a new fashioned cravat. It was reported that the French officers, dressing themselves in great haste for the battle, twisted their cravats carelessly round their necks; and in commemoration of the victory achieved by the Mareschal de Luxembourg over the Prince of Orange on that day, a similar negligent mode of wearing the cravat obtained for it the name of a Steinkerque.

Later the long loose ends were thrust through a buttonhole of the coat. It does not appear, however, to have lasted in fashion much beyond the first quarter of the eighteenth century.

By 1715 the fashion of lace frills had arrived. These were attached to the shirt, appearing from under the neck-band, or stock, and so decorating the opening where the vest was left unbuttoned from the neck down over the breast (Plates 19, 20, 26, etc. Fig. 45 A B). This style gradually supplanted all others in general popularity and was usually termed a jabot. With the introduction of the jabot one finds the “plain folded stocks buckled at the nape.”

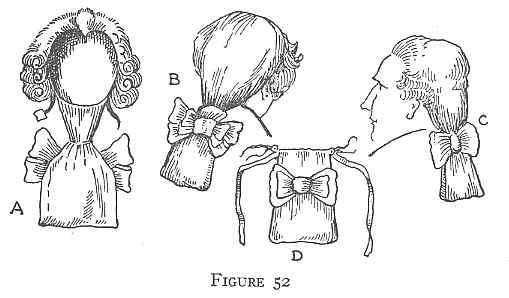

From France and the court of Louis XV came a most attractive and becoming fashion known as the “solitaire.” The solitaire was a ribbon of black silk attached to the bag in which the back hair of the wig was placed (Fig. 52 D). In the beginning the ends of the solitaire were carried around to the front of the neck and were tucked into the shirt, or lost themselves among the frills of the lace jabot (Fig. 48 E). The ends might also be caught in at the throat by a brooch. Around the forties, it was usual to bring the two ends of the solitaire forward, tying them in a bow-knot under the chin (Fig. 48 F). The carefully arranged wig, with its bag and solitaire, the jeweled buckle of the stock, the beauty of the frills of the jabot, and the fine ruffles worn at the wrist were all the marks of the gentlemen.

COIFFURES. – In the Virginia chapter, Section III, mention was made of the great periwigs that came into fashion at the now generally accepted date of 1660. In spite of the great discomfort, untidiness, and expense previously alluded to that accompanied the fashion of wigs, the style continued to grow in favor until, as has been seen, wig-wearing was general among all classes by 1715.

Dating portraits with any degree of accuracy by the style of wig worn is not always possible. There was considerable overlapping in the different varieties, the older men often keeping to their periwigs and fullbottomed wigs long after queues, bags, and pigtails had become fashionable.

Turning to the early advertisements and accounts of these years, one soon discovers that a good wig, made up usually of human hair, was very costly, and at times hard to procure. This resulted in the barbers, for the cheaper grade of wigs, using horsehair, goat hair, and even “hair from the tails of cows,” as a substitute.

Nor did the expense end with the buying of the wig, as great care was necessary to keep it presentable and in good repair. This was usually done by the barber, who was often paid as high as “eight or ten pounds a year” for the care of a single wig. It is not surprising, then, that an article so generally in demand as a wig could be easily disposed of at a good profit, and was therefore especially attractive to thieves. It is doubtful if wigs were snatched from the, heads of their owners as they walked along the streets of Boston, New York, or Philadelphia, as is often stated concerning English gentlemen in London; but that shops and private houses were broken into, the much-coveted wig the loot in mind, is known from the various advertisements, proclaiming the fact by offering rewards for their return, which appeared in the newspapers throughout the eighteenth century.

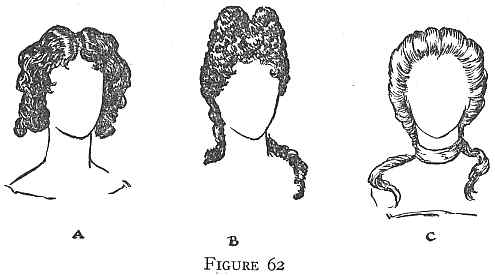

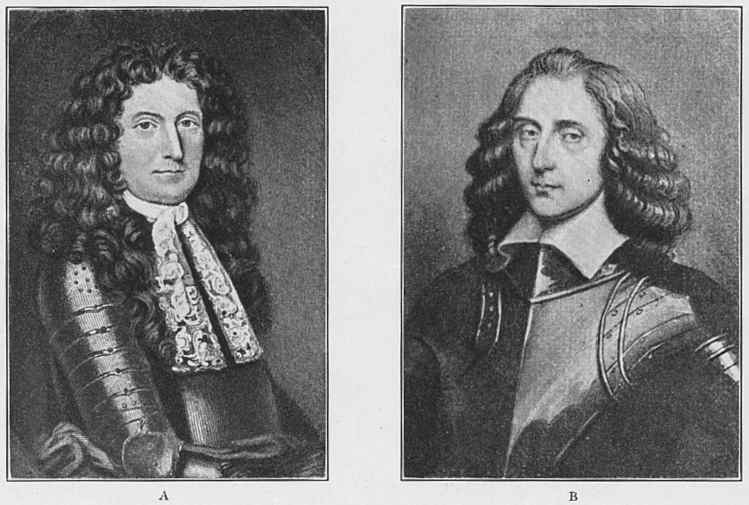

By 1670 the periwig had assumed quite large proportions (Fig. 20 B), the curls falling down the back and clustering over the shoulders. By 1675 it became even more huge and quite artificial in appearance. What is probably the most exaggerated form came into favor approximately around 1690, its chief characteristic being a well defined part in the center, with a high peak in either side of the part (Plates 16, 17, 18, Fig. 20 C), the ends of the wig being separated so as to fall over the shoulders in front (Plates 17, 18). The curls hanging down over the shoulders in front were seldom seen after 1735.

THE PERUKE. – As the periwig continued to grow during the last years of the seventeenth century into a most cumbersome affair of corkscrew curls that hung well over the shoulders, the size and weight must have caused much weariness and discomfort. There is little doubt but that toward the end of the seventeenth century the colonial gentlemen tied their voluminous curls at the back of the head with a ribbon when engaged in hunting and riding, as did their English and French cousins.

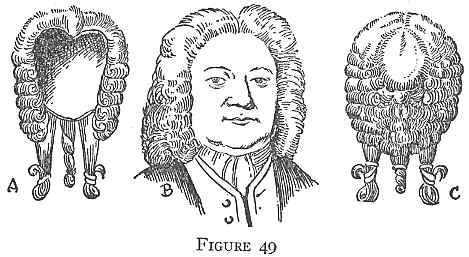

About 1685, however, for informal occasions, the periwig gave way to a less cumbersome wig known as the peruke (Fig. 49). The peruke was used for traveling, riding, and everyday wear. It was known as the campaign or traveling wig. Both the periwig and peruke continued in use until the middle of the eighteenth century. After 1735 the great curled periwig was no longer considered fashionable, and when it is found in portraits after this date it is the older men, especially those in the professions, and not the younger who are wearing them.

The peruke, campaign or traveling wig, then, is a less cumbersome wig worn in place of the curled and loosely hanging periwig. The curls that in the periwig surrounded the face, in the peruke were carried farther back. The back, side locks were turned up into bobs or knots and tied with ribbons. A drawing of the portrait of Governor Ward shows him wearing the peruke (Fig. 49 B). The fullness is carried more to the back, the long lappets and curls, formerly hanging over the shoulders in front, are done away with.

Occasionally one sees in an old painting, as in the portrait of Johannes van Vechten (Plate 21), painted in 1719, a gentleman wearing his own hair, and that unpowdered. This leads one to believe that even in this time of monstrous periwigs there were men who objected to the weight, expense, and discomfort of wig-wearing, and from the untidiness resulting from the use of hair powder.

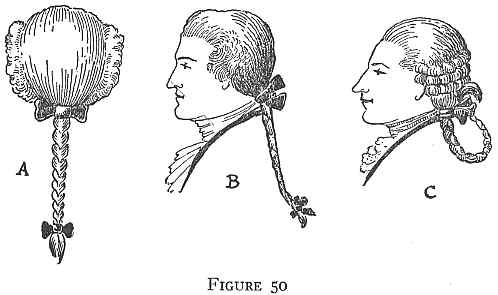

THE RAMILLIES WIG. – The peruke, the traveling wig, and the short bob were all modifications of the great periwig. This tendency to further reduce the size of the wig is apparent as the eighteenth century advances. In Europe in the year 1706 the Battle of Ramillies was fought between the French and the English. The soldiery, with the evident intention ;of freeing themselves of the cumbersome full wigs, are said to have plaited them in a queue. They then placed a black tie at the top, also one at the bottom of the plait. This wig was known as the Ramillies wig (Fig. 50 A). It had quite a vogue in Europe, and soon, due to its comfort and popularity, found its way into the colonies. The Ramillies wig, which must have appeared in America as early as 1706 or 1707, is one of the earliest forms of the plaited queue. The queue was tied with a fair sized bow at the nape of the neck, while the end of the plait was tied with a smaller one.

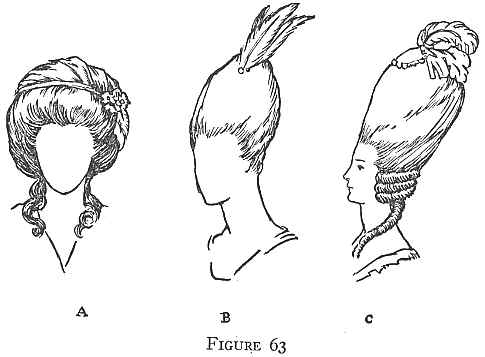

PLAITED QUEUE WIG. – While these wigs were not at first considered for full dress, being only used for the hunt, riding, and everyday wear, yet they were the beginning of the small tie and queue wigs that by 1730 were all the fashion. The new wigs of this date, following the general style of the Ramillies wig, were dressed back from the forehead, arranged in a low toupet, and descended in the back in some form of queue tied with a ribbon.

The plaits, one or two in number, were accompanied by the usual toupet. Pigeon wings, puffs, and curls at the side of the head were much worn (Plates 28, 29, 31, etc. Fig. 50 A). The plait, if long, was sometimes looped up and fixed at the back of the wig by combs or ribbons (Fig. 50 C).

From 1730 on, if one scans the advertisements in the newspapers and gazettes, or reads the many diaries preserved to us from this period, one is confronted, as Dion Calthrop so aptly states, “with a veritable confusion of barbers’ enthusiasms,” derived from some slight trick of fashion in the arrangement of the curls, the puffs, or the queues. In the majority of cases it is impossible to more than surmise what many of these wigs were like. To mention a few, there was a wig called the comet, which evidently referred to a wig with a long tapering queue. Pigeon wings (Plate 31, Fig. 50 A B) referred to the manner of dressing the hair at the sides of the head; the cauliflower, to an arrangement of curls; and so on. Many of the names such as vallancy, the brush, the staircase, convey very little in the way of understanding.

Wigs, without doubt, demanded more care and attention than any other part of the gentleman’s costume. On Saturdays they must be sent to the barbers, where they were brushed and curled. “For tightening the curls of wigs, small rollers of pipe clay (called variously Bilboquets or Roulettes), were used. The curls were wound tightly round these whilst very hot, or as some suppose when cold, and the whole then heated. This last plan, however, would have damaged the wig more than the former.” Late on Saturday afternoons the barbers’ boys would have been seen hurrying back and forth from the shop to the important customers delivering the wigs for Saturday night and Sunday wear. In the larger houses, as in Stenton, Germantown, Philadelphia, there is a recess built into the wall known as the wig closet. Here the gentlemen, with great cloths wrapped around their necks, their faces protected by glass cones, had their wigs, fresh from the barber, powdered by their valets.

The wigs of the majority of men, however, did not receive the same careful attention. In fact, many of the wigs worn by the men of the middle classes must from all accounts have been sorry affairs. Often the discarded head-coverings of the upper classes were won in public lotteries, or were bought at one of the many secondhand wig shops. They were brushed and combed back into some semblance of their previous grandeur, to do duty in a simpler walk of life.

In the colonies the gentlemen of fashion followed closely the latest styles in wigs in London and Paris. Orders from the colonies for wigs in the newest styles stood upon the books of the English wig-makers, to be sent to their patrons in America as soon as the new styles appeared. This was not confined to any one section of the country, but was general in the New England States, the Central and Southern States. Thus it was only a matter of weeks before the latest fashions in England appeared in the colonies.

The different varieties of queue wigs appearing almost simultaneously about 1725 can be placed under certain divisions for the convenience of study. One must realize all these styles were worn at the same time.

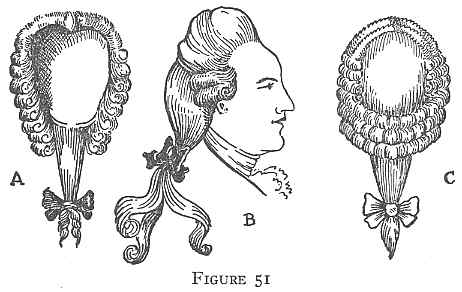

TIE-WIGS. – A very popular type of the queue wig, and one appearing quite often in old colonial portraits, is the tie-wig (Fig. 51). It is dressed, up until the middle of the century, with the early form of the low toupet. It is full at the sides, with the back curls gathered into a bunch and tied with a black ribbon bow at the nape of the neck. About the middle of the eighteenth century the toupet was not worn so flat over the head as formerly, but had grown much higher, being dressed in quite a formal manner (Fig- 51 B).

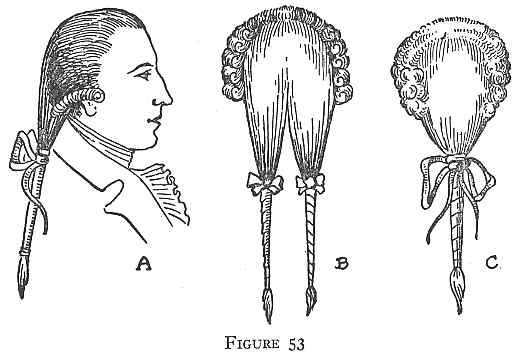

BAG-WIGS. – The bag-wig was evidently a very convenient as well as fashionable way of wearing the hair. The back hair was placed in a square or rectangular bag. The bag was then drawn tight with a drawstring, and a black bow tied at the nape of the neck (Fig. 52). The bag not only served as a decoration, but protected the coat from the grease and powder of the wig. Until 1740 the pigeon wings (Fig. 52 C) were worn over the ears, but after that date were replaced by puffs and rolls (Fig. 53 A). Around the forties the bag was often so large that it practically covered the shoulders of the wearer (Fig. 52 A). It was also to the bag that the silk ribbons of the solitaire were attached (Fig. 52 D).

PIGTAILS. – Pigtails were either one (Fig. 53 AC) or two (Fig. 53 B) in number. They were tightly wrapped in a spiral manner with black silk ribbons. They were tied at the nape of the neck with a ribbon bow. The hair hung free at the end, coming from out the spiral wrappings. They were particularly popular during the reign of George II.

Gradually, about 1770, many men ceased to shave their heads, and wigs, with the exception of those retained by professional men, went out of fashion. Men wore again their own hair, though it was dressed in much the same manner as the wigs – with puffs and rolls, with queues, pigtails, and bags. The hair, however, was still usually powdered. Powder, which had been worn for over one hundred years, finally went out of fashion during the seventeen nineties.

HEAD-GEAR. – By 1670 the brims of the hats had increased greatly in size. This tendency continued until, by 1675, the brims of the hats measured in width as much as six to eight inches. In fact, the brims were so broad that through constant wear they lost their stiffness and had a tendency to fall about the face. To correct this the brims were rolled up, either at one side, in the front, or in the back (Fig. 43 A). They were also looped up and cocked in various ways. In this manner the cocked hat was introduced into fashion. A large feather, or plume, was usually placed around the crown. Hats continued to be decorated in this way until about 1680. Yet from the very beginning of this period the fashion of plumes, ribbons, and feathers began to wane in favor of the edge of the brim being bound with braid, galloon, or even lace. Another very fashionable way of decorating hats after plumes were discarded was to place “a fringe of ostrich fonds along the brim” (Fig. 44 A).

Cocked hats continued to gain in favor, first with one, then with two cocks, until by 1690 it had developed into that most characteristic head-covering of the eighteenth century, the three-cornered cocked hat (Fig. 45 B). By 1700 they were generally worn, retaining their popularity until after the Revolution.

The cocked hat, as a rule, was more often carried under the arm than worn upon the head (Fig. 45A). There were many different ways of cocking the hat. We are told “they are cocked up at all angles, turned off the forehead, turned up one, side, turned up all around,” until the whole appearance of the wearer might be changed from day to day by varying the angles of his cocked hat. The edge of the brim of the cocked hat was usually trimmed with metal lace or galloon. There is, however, a marked uniformity in cocked hats until toward the end of this period, when from 1770 to 1775 the front of the hat was carried up in a high peak (Fig. 46 A).

For indoor wear, there were the négligé caps and turbans. They were worn with the morning gowns or banyans, which they usually accompanied. The turbans became so popular that not only were they worn for négligé, but on many informal occasions as a blessed relief from the hot wigs. In order to understand this continual wearing of caps and turbans and wigs, one must realize that the head under the wig was kept closely shaven. With this protection removed, the wearer seems to have been extremely sensitive to cold and drafts. So true was this, that men wore nightcaps upon retiring, and whenever the wig was removed, whether indoors or out, some kind of head-covering was immediately donned. This was usually the turban (Plates 33, 34). The turban, then, was for informal wear, and was used to supplement the wig, so heavy, hot, and covered with powder. How important a part of the costume it became can be judged by the number of fashionable gentlemen who continually sat for their portraits dressed in banyan and turban. The turban was usually worn perched upon one side of the head in a “very jaunty manner.” Small flat-brimmed hats and round caps edged with fur were worn in place of the cocked hat by travelers and by the sporting and riding fraternity.

STOCKINGS. – The stockings worn in the early part of this period were carried up under the full-cut baggy breeches, and evidently were fastened above or below the knee with garters, probably bands or ribbons; these were embellished on the outside with bunches of ribbons (Fig. 43 A). Stockings could be either worn pulled up over the knee under the breeches (Plates 29, 30, 35, etc. Fig. 44 A B), or pulled up over the breeches at the knee, then gartered below and rolled above the knee (Fig. 45 A). This style came into fashion about 1685, lasting until the middle of the eighteenth century. One reads that “In 1739 russet and green were favorite colors. By revolutionary times, white silk hose were worn by the modish beaux. Stockings for dress occasions were decorated at the ankles with gold and silver clocks.” The fashion lasted from about 1715 to 1790.

In 1731 there appeared in “The Boston News Letter” an advertisement for stirrup hose. Stirrup hose were provided with wide tops, and at that time were no longer in general use. They were probably used to pull on over the stocking and knees of the breeches to protect them from the boot saddle when riding horseback. Knitted homespun stockings, leather stockings, cloth stockings, and “good knit worsted stockings” are all mentioned during this period, and were worn by men and boys who could not afford the expensive silk hose. Other varieties are “Diced hose, masqueraded hose, silk clocked and chevered hose, fine four-threaded Strawbridge knit hose, yarn hose, ribbed, pointed chiveled worsted hose, Jersey-knit hose.”

FOOT-GEAR. – At the beginning of this period under consideration (1675), shoes still retained their red heels, the tongue rising high up over the instep (Fig. 43 A). Shoe roses were no longer met with. In their place the shoe was fastened by strings or ties (Fig. 43 A), or by buckles (Fig. 44 A). The buckles were small at first (Fig. 44 A), being strapped high up on the instep, and were either square or oval in form. In fact, from 1680 on, buckles seem to hay replaced all other forms of fastening and gradually became larger. With the high-heeled, high-tongued shoes one finds, as a general rule, the square ending to the toe, this fashion lasting throughout the first quarter of the eighteenth century.

From 1720 on, the high tongues were gradually shortened, and the decidedly square toes gave way to a shoe with a more natural and rounded shape to the toe (Fig. 44 B). About 1740 the short tongue, natural shaped shoe, with a large buckle over the instep, took its place (Fig. 45 A B, Fig 46 A).

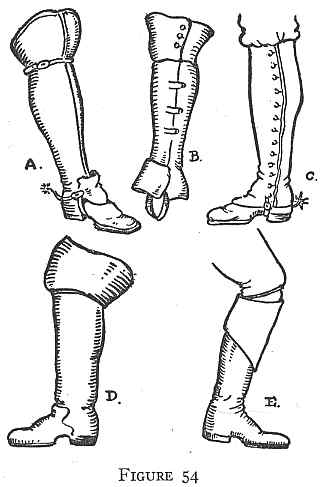

Boots were not a part of the fashionable everyday costume during this period, but were worn more for riding, traveling, and hunting. The favorite boots of the last part of the seventeenth century and the first part of the eighteenth century were the heavy, cumbersome, rigid “jack-boots.” They came into fashion on the Continent about 1660, but it appears they did not come to the colonies until several years later. By 1675, however, they were quite generally worn. The jack boot (Fig. 54 D) was made of stiff leather from. the ankle to just below the knee, where it swelled into a large cup. They were usually provided with large spur leathers over the instep, and to which were attached the spurs. They seem to have gradually lost favor with the gentry toward the close of the first quarter of the eighteenth century. From about 1720 on, they diminished in size and rigidity, until a boot is evolved built upon the same lines, but lighter and more flexible, fitting more to the shape of the leg (Fig. 54 A). A small strap was often buckled around the boot just under the knee to hold it more securely in place.

Over the instep was the spur leather. The boots were probably worn for horseback until the Revolution. From these light jack-boots were developed, about 1700, leggings of leather called spatterdashes. They were often cut in imitation of the lighter jack-boots (Fig. 54 B). Buttons and buckles down the side made them fit close to the leg. They were worn over the shoes. Where the legging met the shoe the joint was masked by a large spur leather, making it difficult not to confuse them with the regular jack- boot. Spatterdashes in the form of high leather leggings were also extensively worn (Fig. 54 c). They buckled under the shoe and buttoned up the side. Mention is made of “Thread and cotton Spatterdashes.” the spatterdashes were used to protect the stockings in wet and stormy weather and were worn especially by sportsmen until the end of the century.

Top-boots made their appearance some time in “the latter half of the century,” and because of their elegant and dandified appearance became exceedingly popular with the young bloods. The top-boot (Fig. 54 E), the lower part of which being fitted tightly over the leg, was made of black leather, usually polished; while the tops, that came from a little below the knee to the middle of the lower leg, were of either brown or white leather. So exceedingly trim were these boots that they became “a portion of their walking dress.”

ACCESSORIES. – The baldric or shoulder-belt (Fig. 42. Fig. 43 A) was still worn during the early years of this period. From it was suspended the small sword. The fashion for baldrics seem to have gone out with the closing years of the seventeenth century, and in its place one finds the sling or the frog appearing from under the vest, and to which the dress sword was attached. The hilt of the sword was often decorated with a large bow-knot of ribbons.

Muffs, both large and small, fashioned out of either cloth or fur, or cloth edged with fur, were carried by men throughout this period.

The taking of snuff was indulged in by most gentlemen of the time, and the handsome snuff-box was to the man of fashion what the fan was to the lady. From the pocket of the coat would appear a corner of a fine lace handkerchief. Probably in the other pocket resided the great comb used for dressing and putting the periwig in order. This was often done in public. Fob ribbons from which hung clusters of seals, exquisitely cut, were attached to the watch. Fobs appeared during the forties.

II. COSTUME OF THE WOMEN 1675-1775

During the last quarter of the seventeenth century America was beginning to sense the increasing wealth and prosperity that were to make life in the colonies during the eighteenth century, until the Revolution, the most comfortable and prosperous in her history. A growing maritime commerce between Boston, New York,. Philadelphia, and Charleston tended to bring these different sections of the country together, unifying the ideas in dress and fashion as between the different elements – the Puritans of New England, the Dutch of New York, the Quakers and “world’s people” of Pennsylvania, and the aristocratic landowners of the South. Thus, dress in America, from the beginning of this period, tended to be more uniform throughout the country. Commerce and intercourse were extremely active and continuous between the colonies and the mother-country, London dictating styles and fashions to America until the eve of the Revolution. Speaking of the dress in the colonies, Frank Alvah Parsons says: The instinct for dress, the fundamental desire for show and personal attraction were no different; the determination not to be outshone and the admiration for the latest and prettiest fashions from England were almost universal, and even where there was a pretence to plain living and an outward expression of piety through its manifestation, the author fails to find any considerable number of instances of individuals who resisted falling into the ways of the world at the first perfectly good opportunity. The few isolated instances are so small in number, that “the exception proves the rule.” As the eighteenth century advanced the Colonies naturally grew in wealth, their commerce (particularly with Britain) increased, and the awakening of a national consciousness resulted. Still, however, regarding with respect the established modes of the mother country, they strove in every way to obtain through friends who were still in England, through colonists who visited the homeland, and through imported ideas in the shape of clothes, to imitate the fashions in a manner becoming their new ideal of national capability. This new national consciousness furnished a stimulus to common desires, and costumes waxed exceeding rich, varied, and showy.

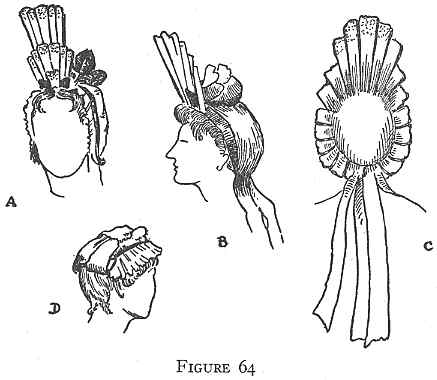

In all this striving to imitate the English styles the fashion dolls, dressed in the latest modes, played a large and most important part. It was by means of dressed dolls that many of the newest fashions first made their appearance in the colonies. Fashion “babies” were dressed by the mantua-makers of Paris; from there sent to the eagerly awaiting and expectant women of London. Many of these dolls, after having set the new styles for the fashionably dressed English ladies, together with new dolls fashioned by the London milliners, continued their journey to the colonies. In this way many new fashions were brought from France and England to far-away America. After they had served their purpose, and their little gowns were no longer capable of stimulating the feminine taste, these dolls were turned over to the children to play with. Thus, in time, many of them were destroyed, partially accounting for the comparatively few survivals of this host of small invaders.

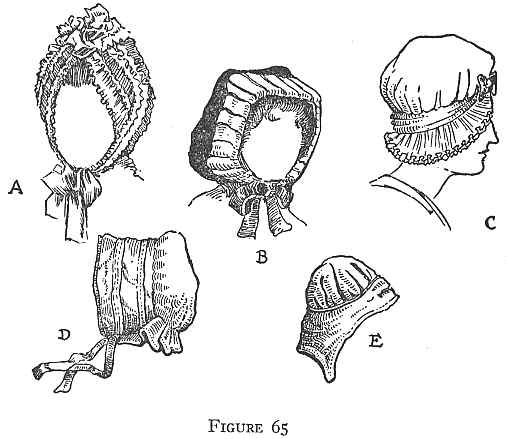

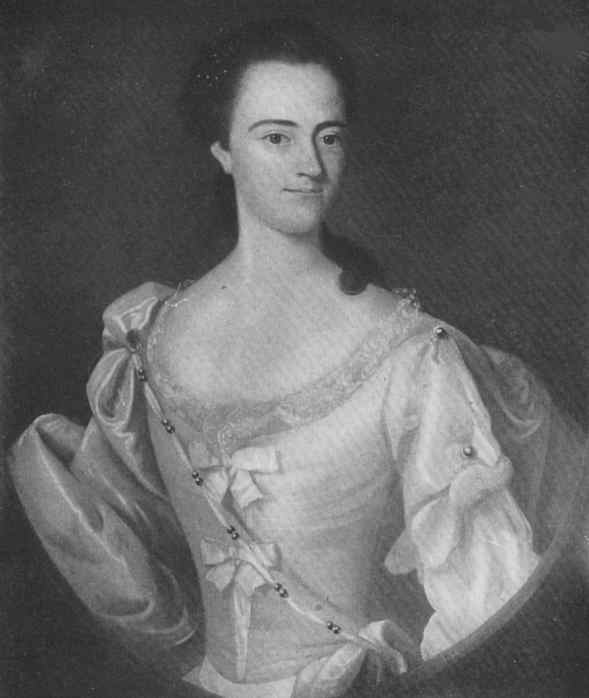

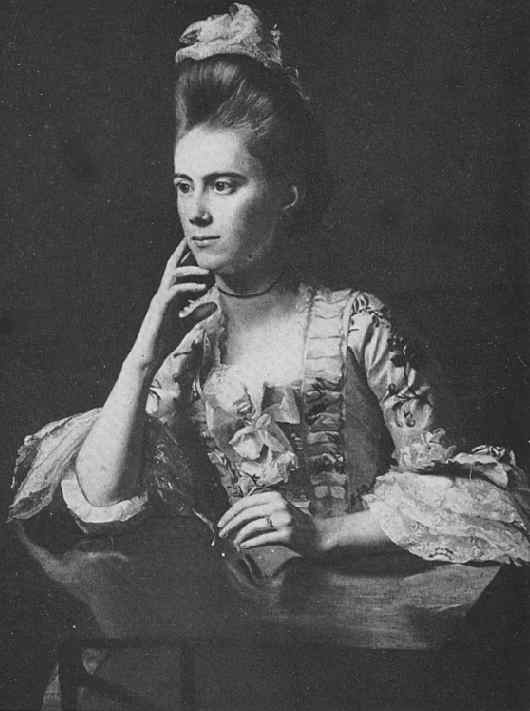

The most fashionable dress worn by women in this present period was the sacque. This garment, hanging from the shoulders over the large hooped petticoat, passed through various changes, retaining its popularity from about 1720 to 1777. The most usual dress, however, and one continually met with throughout these years, was a dress with a long-waisted bodice, which came to a point in front, the neck bared by a medium horizontal or round décolletage, the skirt full. It was in style at the end of the previous period, and carried over into these years with only slight modifications (Fig. 23 A B). “There was,” says Mrs. Earle, “a simple dress, which was worn fifty years ago; before the Watteau dress [the sacque referred to above] was known, was not vanquished while the coquettish French robe was the rage, and continued to be worn after the sacque disappeared, and until the short Empire robes were the mode. I do not mean, of course, that it never varied, but it varied little. It was rather plain, gathered, full ,skirt, a pointed waist, low in the neck, with a ruffled elbow sleeve.” Many examples of this style of dress were ‘seen in the eighteenth century (Plates 49, 50, 51, 52, etc.).

BODICE. – Starting with the bodice from the point left off in the Virginia chapter, one finds the bodice still low cut and long-waisted, coming to a point in front. If fastened down the front, the opening was embellished with bow-knots (Fig. 55 A). The opening around the neck was generally softened by allowing the border of the chemise to appear above the bodice, or, above the bodice, the neck could be covered with a fine scarf or folded kerchief. The horizontal, low-cut bodice was often edged with a lace band or a lace collar (Fig. 55 A), a fashion lasting until the end of the reign of James II. Sleeves to the wrist were no longer fashionable after 1660. In their place are found the elbow sleeves or sleeves that only reach midway (Fig. 55) between the shoulder and the bend of the arm (Fig. 55 A B etc.). Appearing from under the sleeve of the bodice is the full sleeve of the fine chemise, ending in a ruffle of lace. Elbow sleeves with their accompanying ruffles remained in fashion throughout the period (Plates 50, 51, 54, etc.).

The long-waisted bodice might be simply decorated down the front with a band of lace, or it might be left open and worn over a stomacher, being held together in front by lacing or by bow-knots of ribbon, which decreased in size as they descended from the neck to the waist. They were known as échelles (Plate 60, Fig. 55 A), and were popular throughout this period.

Later forms of the bodice, and the one met with from 1700 to the Revolution, differed only slightly from the earlier styles. They were long-waisted and worn over a tightly corseted figure. Sometimes they descended to a point in front (Plates 56, 60). Again, they might be rounded about the waist (Plates 50, 51). The bodice was often fastened down the back, leaving he front perfectly plain, except where it is relieved by lace ruffle at the opening of the décolletage (Plates 50, 51, 55, 56, 57); or softened by the lawn chemise (Plates 48, 57, 58 B). A ribbon bow-knot was commonly placed at the top of the bodice in front (Plates 50, 51, 56,). A ribbon might also be tied around the waist in a bow-knot, usually a little toward the right side (Plates 50, 51). The sleeves of elbow length were similar in arrangement throughout these years, with only slight variations, the fine linen or lawn sleeve, with its accompanying ruffles and laces, appearing from under the bodice sleeve, and falling in rich clusters around the elbow and over the forearm (Plates 50, 51, 54, Fig. 55 B, 56). The ruffles of lace, shorter on the upper part of the arm, were usually graduated in length as they fell away (Plate 60). Besides these charming elbow sleeves, one finds, about 1770, a long sleeve to the wrist coming into general wear.

SKIRTS AND PETTICOATS. – The skirt in the year 1675 was still gathered, as formerly, into small close pleats about the waist (Fig. 23 A). It was, however, usually left open in the front, exposing the petticoats. When split up the front in this manner it was fashionable to loop the skirt up about the hips, holding it in place with knots of ribbon (Fig. 55 A). Until the introduction of hoops and panniers, the fullness of the skirt gathered up about the hips was further exaggerated by a small bustle. Both skirt and petticoat at this time were provided with a train.

Hoops came into fashion between 1710 and 1715.

Planché says: “It is in the reign of Queen Anne that the hoop starts forth again as a novelty.” Sir Roger de Coverley in “The Spectator,” 1711, describes the new fashion thus: “You see, Sir, my great great great grandmother has on the newfashioned petticoat, except that the modern is gathered at the waist; my grandmother appears as if she stood in a large drum, whereas the ladies now walk as if they were in a go-cart.”, The hoop-skirt was a circular arrangement of whalebone. The whalebone hoops started at the waist, gradually becoming larger at intervals as they descended. They might be attached to a canvas petticoat; or later, about the middle of the century, they were made in two side pieces to enable the wearer to handle them more easily.

It appears they were quite round and funnel-shaped at first; but during the next few years they became more and More flattened in front and back, projecting out in varying widths on both sides over the hips (Plates 50, 51, Fig. 55 B. Fig. 56). Instead of forming a circle, the shape of the skirt was now more oval, in which fashion they were worn throughout the period.

With the introduction of hoops the trains gradually disappeared, until in a few years skirt and petticoat touched the ground all the way around. From 1730 on, the skirt and petticoat were not unusually of ankle length, especially for everyday wear; while for dress occasions they reached the ground (Fig. 55 B. Fig. 56). It is strange so few of the paintings show the skirt opened in front and displaying the fine petticoat, so general at this time (Plates 52, 53 B). The skirt is more often shown closed (Plates 51, 58). When the skirt was split up the front it might be gathered full over the hips, from there hanging free, revealing a V-shaped section of the petticoat (Fig. 56). Another manner of wearing the split skirt was to gather it up in the old manner and fasten it in panniers at the side (Fig. 55 B).

GOWNS. – When the bodice and skirt are made in one piece it is referred to as a gown. The bodice of the gown, however, did not differ from the bodice made to wear separately with a skirt. The skirt of the gown might hang from the waist over the hooped petticoat (Fig. 56), or could be looped back over the hips with “narrow braid and buttons” (Fig. 55 B). The décolletage, from the early years of the eighteenth century, tended to a round (Plates 49, 50, etc.) or a square cut neck (Plates 52, 55, etc.). The bodice of the gown was often left open in front, where it was worn over a richly embroidered or laced stomacher, the stomacher being fastened to the two sides of the bodice (Plates 47, 60, Fig. 56). The stomacher was further embellished with a row of ribbons down the front, the échelles, and the edge of the décolletage was decorated with a band of lace.

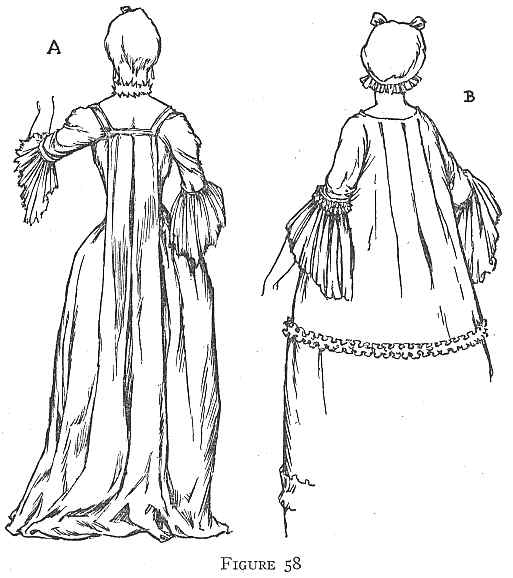

A most fashionable dress for women of the eighteenth century, from about 1720 until the end of the Revolution, was the loose-bodied sacque, or full gown, that hung from the shoulders with great fullness in the back, spreading out over the hooped petticoat. About 1740 the fullness of the gown in the back was brought into a series of box pleats, attached to the top of the bodice at the neck. From here they descended to about the waist, where they lost themselves in the fullness of the skirt. (Plate 53 A, Fig. 57. Fig. 58). The sacque might be worn either open all the way down the front, exposing the petticoat and stomacher, or open to about the waist (Fig. 57 A) or, again, closed. The sleeves followed the general fashion, coming to about the elbow, and finished with ruffles.

This French sacque is generally spoken of as the “Watteau gown,” and the box pleating in the back as “Watteau pleats.” A more suitable name for it, however, is the robe á la française, for as Messrs. Kelly and Schwabe point out, in speaking of this gown, “At first hanging loose behind, the sacque in the thirties merges into the robe á la française, the gown with the misnamed ‘Watteau pleats’ (which in their full developed form are never found in Watteau’s pictures).” The body of the gown is made at times to fit the figure quite close, with the two pleats hanging down the back, merging from below the waist into the fullness of the hooped skirt (Fig. 57 B, Fig. 58 A). Later in the period the box pleating, instead of hanging freely from the neck, was brought in and sewn, flat to the back of the bodice.

From France came a new gown, the polonaise, that was to be exceedingly popular as well as fashionable in the colonies during those years just previous to the Revolution, and during the early years of the new Republic. In France it was a less fashionable gown than the robe à la française, the latter being the gown of cereniony in that country until hoops went out of fashion in the eighties. The body of the gown fitted close to the tightly laced figure and came to a point in front (Fig. 59 A B). Two pleats, or ruffles, came from the back of the neck over the shoulders, from where they fell away into a rounded front. The full skirt in back was sometimes looped up with ribbons, forming three festoons in the back, or was allowed to hang uninterrupted over the hooped petticoat (Fig. 59 B). The petticoat, after being hooped out from the waist, fell quite vertical (Fig. 59 A). It reached to a little above the ankle, the hem usually embellished with a wide box pleating. The bodice was laced over a stomacher, with a “silk cord through eyelet holes.” The gown was cut low, baring the shoulders (Fig. 59 A) The neck, however, was often covered with a folded shawl or fichu of lace.

RIDING COSTUME. – The first means of traveling and of communication between the different settlements in the colonies were either by following the streams and rivers in boats and canoes, or on foot, threading the forestways along old Indian trails. Gradually the trails and blazed paths through the forest widened into roads, making horseback riding possible. Even after carriages and stage-coaches came into general use, horseback riding remained by far the most popular way of getting around until the close of the eighteenth century.

Seated apillion was the usual way women and children rode about in the early days, the custom for women to ride alone coming in “late in the seventeenth century.” The pillion, however, remained in general use until the end of the eighteenth century. The pillion was a leather or padded cushion on a wooden frame, measuring about a foot and a half in length and ten inches to a foot in width. A sort of platform stirrup, or footboard, hung from the offside. It was strapped to the horse’s back just behind the saddle. A metal handle, or strap, was fastened to the framework of the pillion, to which the rider could cling for safety. In place of this the pillion rider sometimes steadied herself by placing her arm around the rider, or by clinging to a heavy leather belt strapped around the man’s waist for this purpose.

There was no specially designed riding costume worn by the women in these early days. They protected their garments from being splashed with mud and dirt by donning a cloak and pulling over their skirts a garment called a safeguard, weather skirt or riding petticoat, which was made out of some stout material, usually a heavy linen. Safeguards seem to have been worn as a protection as long as women rode horseback. While the safeguard served for all general purposes in the colonies, there appeared late in the seventeenth century advertisements in the London papers, as well as in writings, in letters, and diaries, descriptions of a new fashionable costume especially designed for hunting and riding, which soon found its place in the wardrobe of the well-dressed woman of America.

One of the earliest descriptions of a costume that might be considered as being made especially for riding appears in Pepys’s Diary under date of July 13, 1663. Pepys, while strolling in the park, saw the king and queen riding by, and upon his return home made the following entry relative to the riding costume worn by the queen: “… a white laced waistcoat and crimson short pettycoat… in this dress, with her hat cocked and a red plume.” In a news letter of the year 1682 the ladies of the English court are described as taking the air on horseback “attired very rich in closebodied coats, hats and feathers with short perukes.”

Planché also refers to an English riding-dress that was advertised for sale in 1711, the costume consisting of “coat, waistcoat, petticoat, hat and feather all well laced with silver.”

Many advertisements appeared in the London newspapers of the eighteenth century, advertising lost or stolen garments, and among the many descriptions, the following, published in 1712, describes a lady’s riding costume: “A coat and waistcoat of blue camlet trimmed and embroidered with silver, with a petticoat of the same stuff, by which alone her sex was recognized, as she wore a smartly cocked hat, edged with silver and rendered more sprightly by a feather, while her hair, curled and powdered, hung to a considerable length down her shoulders, tied like that of a rakish young gentleman, with a long streaming scarlet band.”

One of the earliest references made to the riding habit appears in 1727, which reads: “riding habits with hats and feathers and periwigs.” During the eighteenth century, riding-habits were called by various names, the Brunswick, introduced in England about 1750, being the one most generally met with. As in the case of those previously described, it was made in the masculine mode of coat and waistcoat.

Along with other imported clothes came riding costumes and habits. The two figures in riding costumes (Fig. 60 A B) illustrate the equestrian dress as similar to the descriptions given above. In Figure 60 A the coat, built upon masculine lines, is brought in close to the tightly laced waist, with skirts that flare out over the full petticoat. The sleeves are turned back into great elbow cuffs, held in position by loops and buttons. Under the coat is worn, in place of the waistcoat, a low cut bodice. A cocked hat, decorated with lace fonds and plumes, very mannish in character, is placed upon her head, completely hiding the hair in front and at the sides.

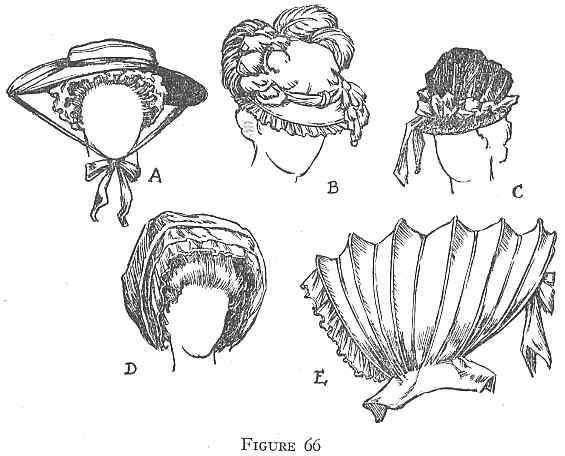

A riding-habit decidedly more masculine in appearance is shown in Figure 60 B. The coat, tailored upon straighter lines, is not brought in so tightly to the waist, and is worn over a waistcoat that ends a few inches above the line of the coat. At her neck is a stock with the two ends of the cravat hanging down over waistcoat. A cocked hat rests upon a peruke, or upon her own hair dressed to resemble the fashionable mannish wig. The back hair was occasionally placed in a bag and the solitaire worn over the cravat. For a description of women’s riding costume up until the opening of the nineteenth century see Chapter VII, Section II.