Contents

Contents

Introduction

The Revolution proved to be more than a successful rebellion against the armed forces of England. It was the first campaign of the new liberalism against the old order of things; the forerunner of a greater revolution in humane thought and practice that was to sweep through the world. During the last quarter of the century it made its way, sometimes violently, sometimes imperceptibly, transforming the political, social, and economic scaffolding of America and Europe. After its passing it could be seen that the design of human society had been altered and that a new one was taking shape. The young nineteenth century was free to launch its hopes and experiments in more enlightened and democratic channels.

The war left the freed States exhausted and a little dismayed. The new independence was at once a wonderful and a terrifying thing. There was a growing realization that it entailed more than a mere separation from England; that a national consciousness and a governmental framework were necessary, and that these were not to be achieved without struggle and pain.

Seven years of war had left its scars from Vermont to Georgia. Fire and pillage, the disruption of commerce and industry, the departure of large bodies of loyalists with their wealth and chattels, the debasement of the currency, and the wastage in men and material had drained the vitality of the country. Fortunately, America’s frontierlike civilization had weathered the storm of war better than was possible in more complicated and centralized communities. It was still a civilization of small, self-sufficient units – farm households in which almost everything necessary for maintaining existence could be produced. Although these households felt the pinch of war conditions, yet in no essential was their mode of living changed from that of pre-Revolutionary times.

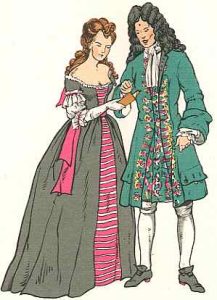

It was in the cities and towns the greatest change occurred. During the British occupation the larger cities, like Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and Charleston, had been centers of the most extreme gaiety and fashionable life. Probably never before nor since were there episodes of such color, luxury, and brilliance in American history. The color and brilliance departed overnight with the beaten British armies. Nothing was left to take its place. Those families of wealth and station still remaining either were more soberly inclined or were restrained from any display of ostentation by the new democratic catch-cries in the air. The phrases of the Declaration were in circulation, and none cared to risk the epithet of “aristocrat.”

The growing restraint in dress was due partly to the lack of imported materials, commerce with England having been cut off during the war, and contact with other countries hazardous because of the British blockade. With the signing of the treaty, new life began to stir on the deserted wharves of the seaport cities; for America was now free to trade with the world unhampered by navigation acts or Board of Trade restrictions. The country’s young strength asserted itself, and in a remarkably short space of time she had repaired the ravages of the conflict and was winning a place in the world’s commercial and industrial spheres. The hatred toward England was still intense, and many wished nothing England could give of its art and industry. In the excitement of independence, some hoped for a new, vaguely democratic art to spring from the soil of the liberated country. Most cast about for their models among the older nations of Europe.

France was the chosen country. She was popular because of her aid during the Revolution; large numbers of her émigrés had found homes in America, bringing with them French culture and a taste for French art; she was working out a new phase of the classic revival, which, when it crystallized into the Empire style, was to leave its mark on the art of all western Europe and America.

During the last quarter of the century French influence on American costume and on art was evident; but it is interesting to note that even when dislike of things English was general, and when conscious efforts to eliminate all English characteristics were being made, yet under the newly acquired French veneer the English foundation was always visible. It was impossible for the new Republic to disavow, much less to hide, its ancestry.

The upheavals of the late eighteenth century finally reached the field of dress. The weight, expanse, and

cumbersomeness of the costume had attained such dimensions that nothing short of a reaction could suffice. High head-dresses, hoops, voluminous skirts, powder and patches, high-heeled shoes, and large broad-brimmed hats were discarded. In their place, through the closing years of the century, came the grace and simplicity of the Empire style – lower coiffures, the straight, clinging lines of the gowns, the low-heeled shoes and sandals, the turban head-dresses, and the use of thin, semi-transparent materials. For the women, the new fashion was just another swing of the pendulum. Presently they would go back to hoops, full skirts, and tight bodices. The men committed themselves, however, to a type of dress that leads down to modern times in a straight line. Their trousers were reaching to the middle of the calf, and on their way to the shoe-top. Wigs had vanished and color was going. Male costume had turned another comer and was on its way to the drab present.

I. COSTUME OF THE MEN 1775-1800

One is apt to suppose that during the years just previous to the Revolution, and the actual years of fighting that followed, men would have had little chance to think of dress. Probably for a time uniforms were given more special attention than the cut of a coat. Men in civilian life, however, dressed, if not always in the finest stuffs, yet with all the nicety of detail they had previously observed.

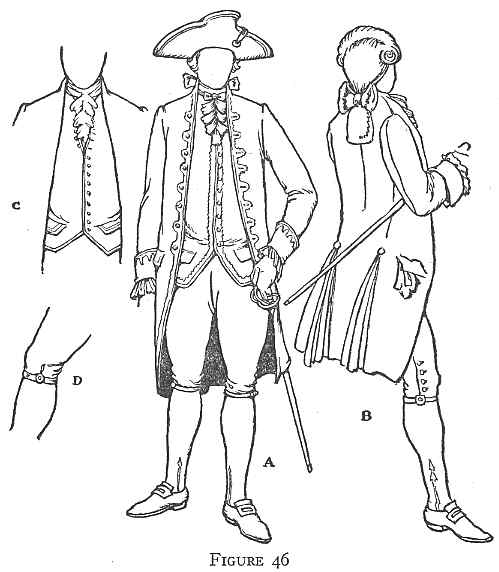

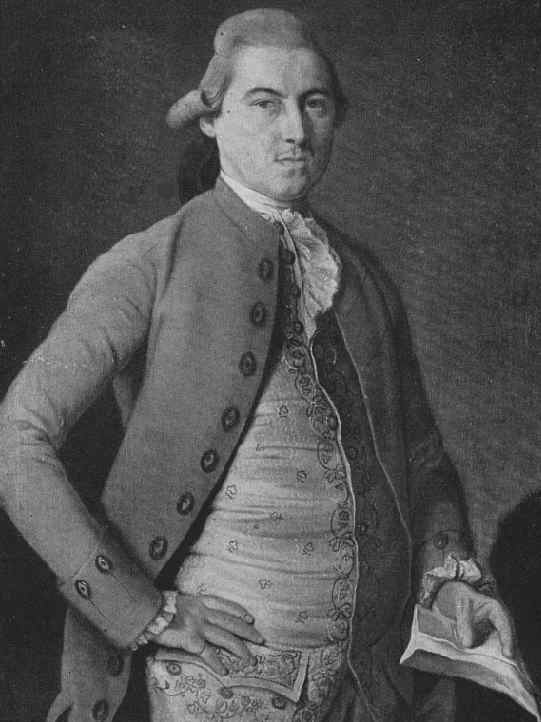

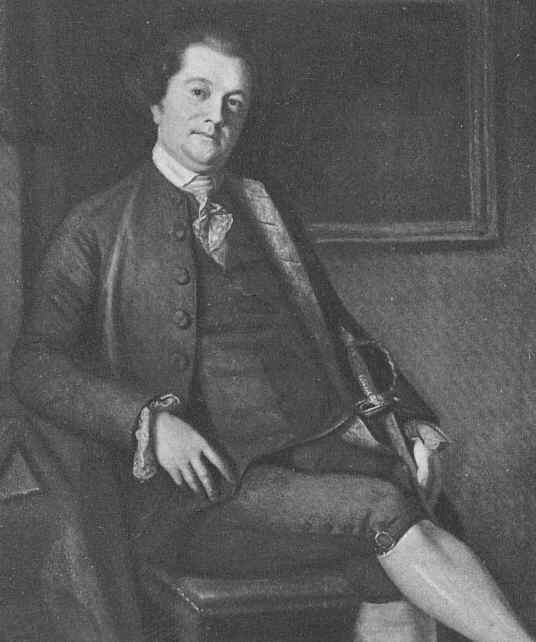

BODY GARMENTS AND BREECHES. – The coat, waistcoat, and breeches as described in Chapter V, (Plates 36, 37 Fig. 46) will also answer for a man during the period of the Revolution, and until 1800. Thus, the dress coat remained about the same. The sleeves were worn quite tight, with a small cuff at the wrist, the front sloping away to the back in two narrow coat-tails. The pockets were placed upon the hips with small flaps. The side pleats, set more to the back, were pressed flat and were much smaller in size than formerly. The waistcoat buttons went to a little below the waist-line, the waistcoat having a short skirt. The knee breeches button and buckle were at the side of the leg, the breech’s band fastening over the silk stocking. They fitted over the leg, were made full in the seat, and gathered to a tight waist-band (Plates 37, 38, 39).

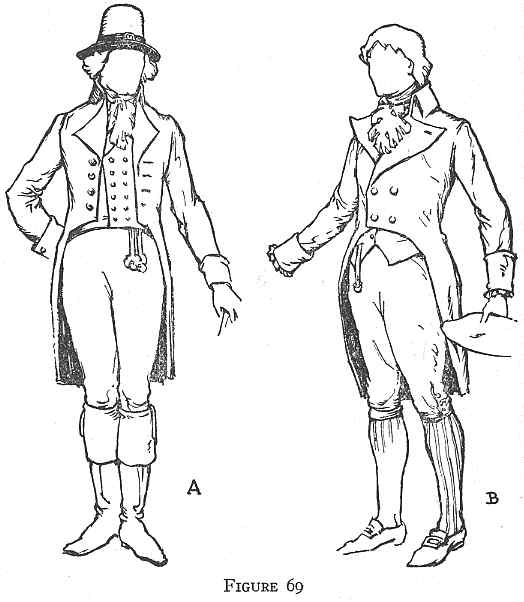

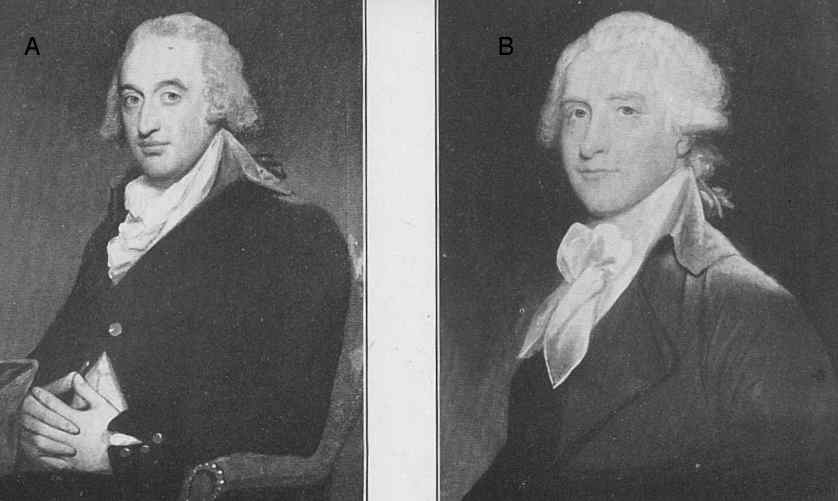

In 1780 a new fashion in coats for ordinary wear made its appearance. The coat for more dress occasions was the one just described. The new coat gradually grew in favor, until in the early nineties it was worn for all occasions. The new-fashioned coat (Fig. 69 A) was made in a high-waisted, double- breasted style, with a deep cut-out in front from a little above the waistline; from there it fell away in the back to a longtailed skirt. A characteristic detail in the nineties was the high collar and broad lapels (Plate 41 A B). The sleeves were close and extended to the wrist with a small cuff. Small lace ruffles might (Fig. 69 B) or might not (Fig. 69 A) appear at the wrist. Waistcoats, which had been quite short, were cut still higher in a straight line across the front. They were double-breasted and might or might not have large lapels. The waistcoat, cut still higher, conformed to the shortened cutaway coat, though three inches or so of vest showed from under the buttoned-up coat (Fig. 69 A B).

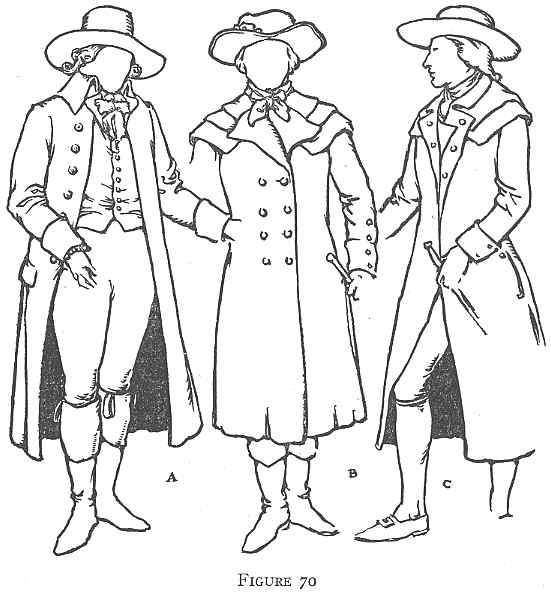

From the middle of the eighties, when the double-breasted waistcoat developed the large lapels, it became fashionable to wear the lapel of the waistcoat turned out over the lapel of the coat (Plate 41 A. Fig. 70 A).

From the beginning of the period one finds skintight buckskin riding-breeches (Fig. 70 A). From the nineties on, all fashionable breeches were tailored to fit tight to the thighs and were not supposed to show any wrinkles or creases.

OVERCOATS. – Overcoats in the style of the earlier period were still worn. They were usually termed riding-coats, but were generally worn for coaching, traveling, or even walking. The coat (Fig. 70 B) is a double-breasted riding-coat, probably made out of serge or kersey, with two rows of buttons down the front. The coat is long, almost covering the legs, and without much shape. The large revers, or lapels, lie over the chest. Around the neck is the triple cape.

In the eighties the overcoat (Fig. 70 C) was a little more fitted to the waist. It was left open and the revers were buttoned back. The skirts of the coat were full and long; the sleeves closed with small cuffs. Two small capes encircled the neck.

In the nineties one meets with a riding-coat with an extremely smart cut (Fig. 70 A). The collar is carried high up about the neck in the fashion of these years. When buttoned, it was made to fit slightly in at the waist, the skirts hanging a little full from the waist down.

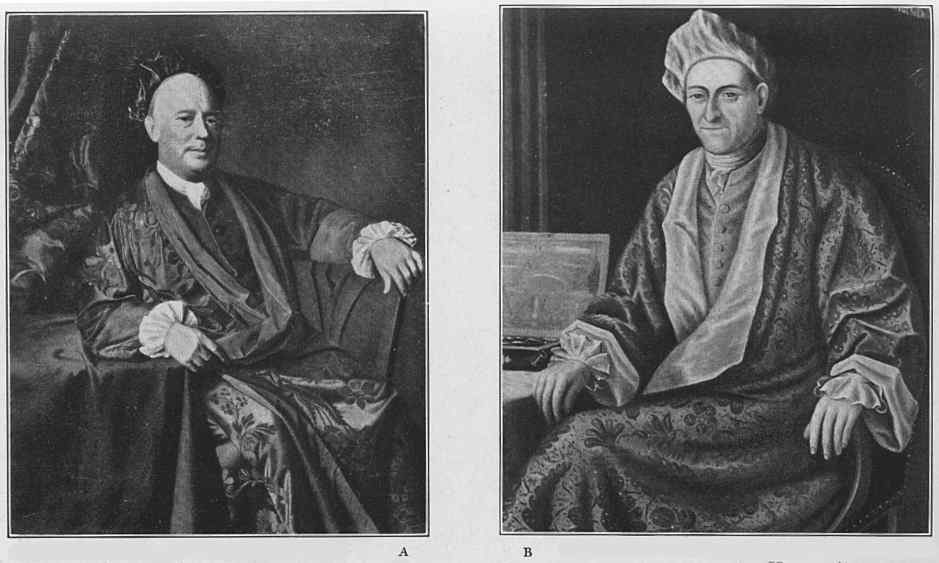

Banyans and morning gowns were fashionable to the end of the century (Plates 33, 34).

LINEN. – Ruffles of lawn or lace still appeared from under the coat-sleeve at the wrist (Plates 38, 39, 40), gradually, however, growing less in evidence, until by the nineties they had generally disappeared (Plate 41 A. Fig. 69 A). The plain folded stock, buckled in the back with a frill of lace, the jabot decorating the opening of the waistcoat at the throat, was worn throughout the period (Plates 40, 41 A). At times the jabot was quite small and almost hidden by the waistcoat, which was buttoned almost to the throat (Plate 34). From the beginning of the period one meets with a new form of the cravat. A “muslin neckerchief” was tied at the throat in a large bow, the ends of the bow tie spreading out over the waistcoat front (Plate 41 B).

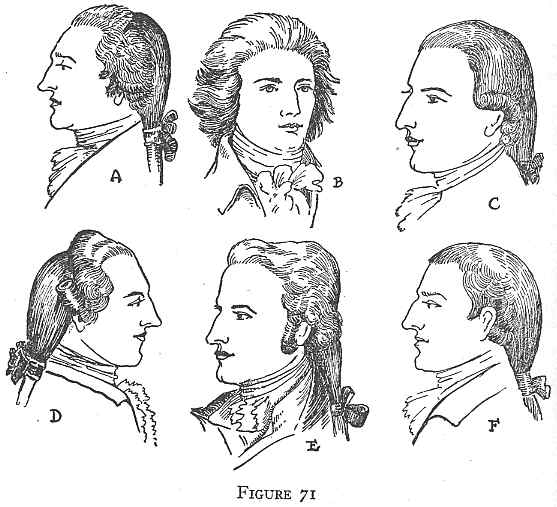

COIFFURES. – The wig was worn in all the different forms of the queue dealt with in detail in Chapter V, Section 1, and continued by many to be worn in that style until near the close of the century, when, for general wear, they went out of fashion. Toward 1770, however, it became quite customary for the men who were not bald, or whose hair had not been ruined by wig-wearing, to cease shaving their heads. When the hair was of sufficient length they discarded the wig. The natural hair, moreover, was dressed in imitation of wigs. When powdered it was exceedingly difficult to determine in portraits whether the man was wearing his own hair or a wig.

The natural hair, dressed up in the back in a queue, was often left unpowdered. In fact, powder for everyday wear was usually omitted as early as 1760, and went out of fashion in the nineties.

From the eighties one finds the hair occasionally dressed in a studied, négligé style, in what was termed a “disheveled crop” (Fig. 71 B). A curl or puff was sometimes carried over the top of the head from ear to ear, a fashion that came in during the eighties. The back hair was done in a pigtail queue (Fig. 71 D); or a small puff was placed at each side of the head over the ear, the hair brushed back from the forehead. and with the back hair likewise made into a queue (Fig. 71 c). This could be varied by dressing the hair in a puff over the top of the head, and in place of puffs at the side of the head the hair would be frizzed over the ears (Fig. 71 A). One of the plainest methods of dressing the hair was to brush it smoothly back from the brow without its being puffed, curled, or frizzed (Fig. 71 F). If the hair was thick, it might be brushed full over from off the forehead (Fig. 71 E). While the pigtail queue was the more usual way of fastening the back hair, at times it was brought into a simple tie or thrust into the bag. In the full length portrait of Washington painted by Gilbert Stuart, in the costume worn by the President at the time of his second inauguration in Philadelphia, the ribbons of the bow fastening the bag can be seen over his left shoulder.

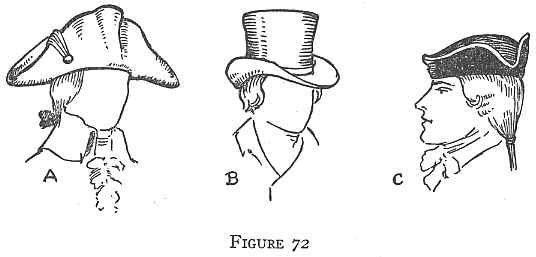

HEAD-GEAR. – The cocked hats worn by gentlemen retained their popularity more or less throughout the period, varying considerably, however, in size, angle, and style of the cocked brims. From the seventies on, the front peak was generally carried high up (Fig. 72 A). In contrast to the hat cocked high in the front, there is, from the eighties on, the much abbreviated form worn by the dandies and known as the Nevernois hat, which probably was the last phase of the cocked hat (Fig. 72 C).

A very favorite hat appearing in the seventies was the round-crown, broad-brimmed felt or beaver hat (Fig. 70 A C). Occasionally the brim was rolled up on one side. This hat was much worn for traveling, riding, hunting, and undress. From the eighties one meets with a new fashion, hats with flat or narrow brims and high, tapering crowns, (Fig. 69 A) . Around the crown a band and buckle were usually placed. During the next ten years, or from the nineties, one finds the top-hat with varying contours to the sides of the crown, and the roll of the brim (Fig. 72 B).

STOCKINGS. – Silk stockings, usually clocked, were worn under the breeches generally throughout the period. Striped stockings came in in the late nineties (Fig. 69 B).

FOOT-GEAR. – The low shoes were of quite normal shape, with rounded toe and low heels, the short tongue coming over the instep and fastened by a large square buckle (Plates 39, 40, Figs. 69 B, 70 C). Leggings of leather, spatterdashes, and top-boots, referred to at length in Chapter V, Section I, were worn throughout this period, especially in the country. Top-boots became extremely fashionable for general wear from the nineties on (Fig. 69 A). The lower part of the topboot, made of black leather and highly polished, fitted tight over the calf of the leg, while the tops of brown leather came some inches below the knees. For hunting and riding, top-boots were worn with skin-tight buckskin breeches.

ACCESSORIES. – Swords were hardly ever worn now, except on state occasions (Plates 39, 40). In their place men carried sword-canes. Canes were carried generally throughout these years. A little before 1800 the heavy club sticks became fashionable. Now, as in previous years, the snuff-box was an indispensable part of a gentleman’s attire.

II. COSTUME OF THE WOMEN 1775-1800

During the Revolution, extremes of rich and plain attire in women’s dress were most marked. In the large cities, especially in those occupied from time to time by the British, balls, dinners, dances, and parties kept fashion uppermost in the thoughts of the ladies; while throughout the country districts the majority of women dressed as plainly as possible, wearing domestic materials and curtailing expenses wherever possible in order to send help to their men who were fighting.

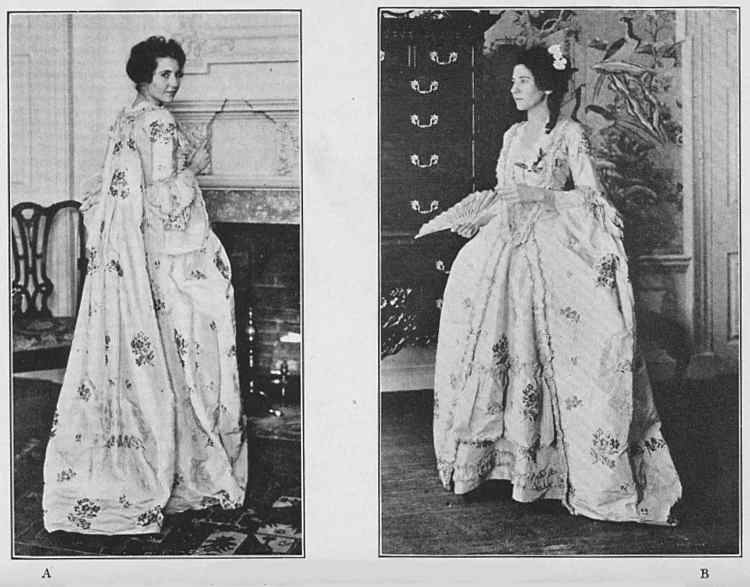

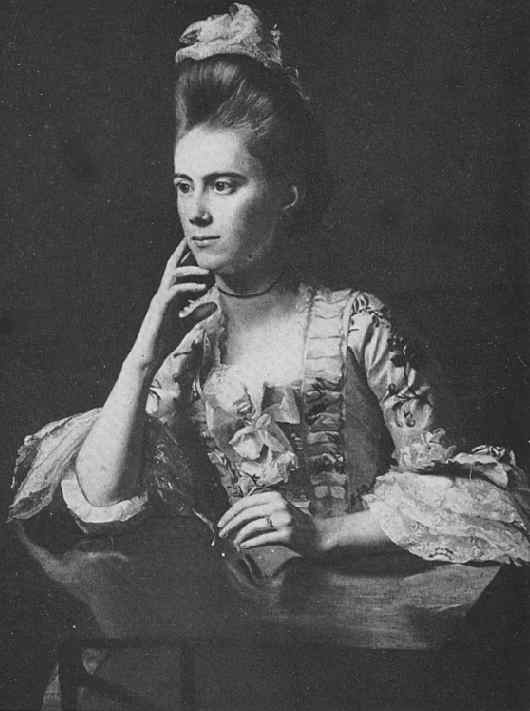

BODY GARMENTS. – Bodices remained much the same in shape and style as in the last years of the previous period, continuing so until about 1780. They retained their long-waisted shape, either closed or open, and laced over a stomacher. The low-necked gown remained in fashion, with sleeves usually of elbow length, though a close sleeve to the wrist came in early in the seventies and was to become more and more fashionable. The sacque, the robe à la française (Plate 53), or the polonaise (Fig. 59) both lasted until the eighties. In the sacque the box pleats were sewn tighter to the body, and “the full pleat from the shoulder down the front went out.” From 1777 on, hoops and panniers were less and less worn, except on dress occasions. In place of the hooped skirt, one finds, toward 1780, the skirt attached to the bodice around the waist with small drawn gathers, and these either bunched, reefed, or looped over a quilted petticoat (Fig. 73 A).

The neck and shoulders left bare by a low-cut bodice was retained until the nineties, though the fashion of covering the neck above the corsage with fine linen and gauze scarfs and fichus increased. The abbreviated sacque (Fig. 73 B C) and polonaise (Fig. 73 A) were extremely fashionable until 1790. Many women, as the year 1790 approached, tended more and more to follow the masculine mode of dress. The cut jacket and coat were very fashionable. The coats were made with lapels fastened across the front with buttons and loops (Fig. 73 D E).

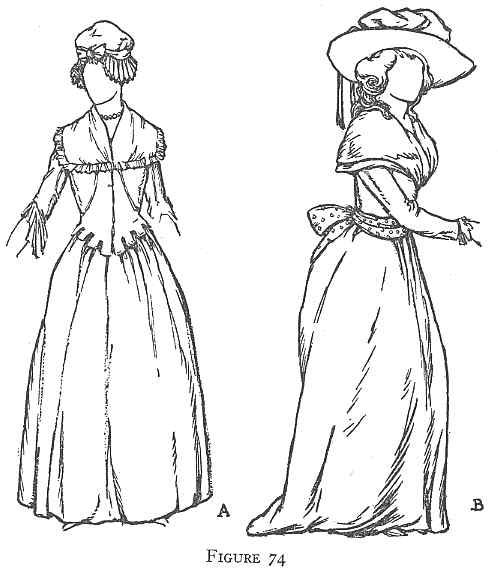

A change in the style of women’s costume came in about 1780, panniers and hoops being now more or less worn. The bodice, though still cut low in the neck, became shorter and less pointed in front, or was cut low in front and finished with tabs below the waist-line, the sleeves fitting close from the shoulder to the wrist. Above the corsage the neck was filled in with a fichu (Fig. 74 A). With the gradual disuse of the hoops and panniers the full-gathered skirt attached to the bodice was held out in the back by a bustle. This occurred all through the eighties (Fig. 73 C).

There was also a simpler type of dress consisting of a low-cut bodice with a medium full-flowing skirt gathered around the waist, which was not held out in the back by a bustle. Around the waist was worn a wide scarf or sash, tied in a bow either in the back or at the side (Fig. 74 B). To the bodice might be attached either short full sleeves edged with a frill or ruffle, or the long tight sleeve to the wrist. It was in the middle eighties that womankind conceived the absurd idea it was most becoming to look like a pouter pigeon. To secure this desired effect the kerchief of gauze or fine linen, called a buffont, was arranged to give “an exaggerated bosom.” A book on costume gives the following definition of buffonts: It was “a fine projecting covering for a lady’s throat and breast, made of gauze or lace or linen. It was confined by the bodice and puffed out above like the breast of a pouter pigeon” (Fig. 74 B).

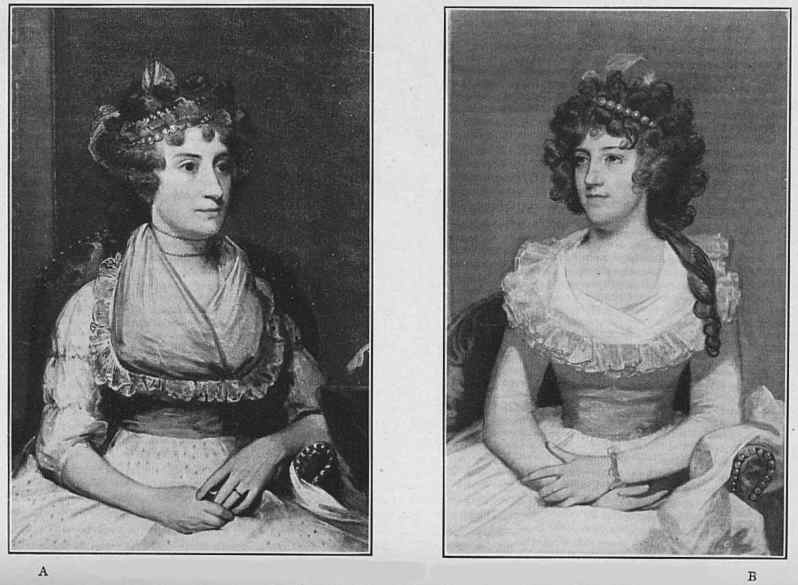

Another change occurred in women’s costume about 1790, when the waist-line was again raised. The neck was bared in a deep, round décolletage, edged on the under side with a full lace ruffle (Plate 64 A B). Above the corsage the neck was covered with a fine gauze (Plate 64 B) or by a buffont (Plate 64 A).

The fur-trimmed pelisse was still worn as a fashionable wrap (see Chapter V, Section II) throughout these years.

Between 1795 and 1797 a decided change may be noted in women’s dress. Suddenly hoops and panniers, full skirts of “stiff brocades and rustling silks,” that had held sway for so long, went out of fashion, and one is introduced to the styles of the French Republic. With the introduction of the new style, not only hoops and full skirts went out of fashion, but high-dressed hair, powder and patches, large hats, and high-heeled shoes were all put into the discard. From then on, fashions changed with great rapidity, a multiplicity of styles coming in with the dawn of the nineteenth century. The new gown was made with a short bodice, accentuating the high waist-line now the fashion (Fig. 75 A B). The narrow skirts were made of soft clinging materials. The bodice was still cut low in the neck, with either a round (Fig. 75 A) or a square (Fig. 75 B) décolletage, usually left uncovered; though for out-of-doors, long scarves (Fig. 75 A) were thrown about the shoulders, almost reaching the ground.

RIDING-HABITS. – (Continued from Chapter V, Section II)

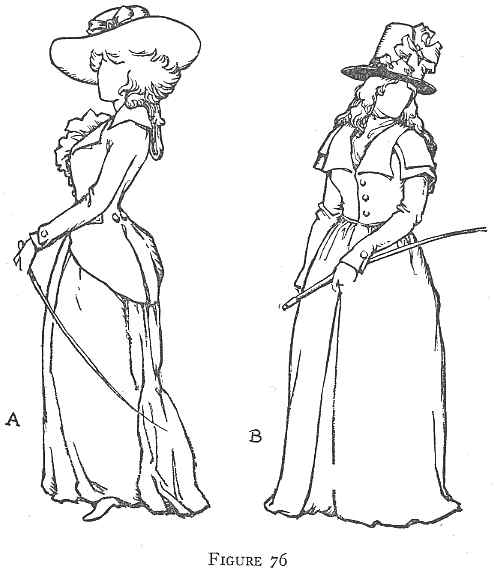

From the “Fashionable Magazine” of August, 1786, there is a plate showing the riding-habit of that time. From it the authors have made a drawing which is reproduced here (Fig. 76 A). Although the magazine was an English publication, there is very little doubt but that the style was soon found here in America. While the habit is still tailored along masculine lines, the long full-skirted coat is no longer in evidence. The coat was made to fit close over the tightly laced figure, the skirts of the coat falling away into two coat-tails in the back. The coat was provided with lapels and was open at the throat. Large buttons fastened the coat together in the front. The sleeve, as fashion then dictated, was close-fitting from the shoulder to the wrist. Probably the coat was worn over a vest, while at the neck a ruffled frill of lace was seen. In place of the cocked hat, the large wide-brimmed hat of the period was worn – an extremely impractical selection. As a hat of this type would be unsuitable for a journey, or for a ride of any distance, the riding-hood would, of necessity, be substituted for the picturesque “Gainsborough” hat.

During the nineties one meets with the long ridingcoat (Fig. 76 B), which had revers or lapels, and buttoned down the front. It had several small capes over the shoulders, in imitation of the box-coats worn by the stage-coach drivers. The front between the turned down lapels could be filled in with a buffont, or with a rich frill of lace. While the three-cornered cocked hat was still worn at this time for riding, the more fashionable hat was the tall-crowned, flat-brimmed felt or beaver, decorated with bands, bunches of ribbon, and buckles. It seems to have been an exceedingly popular habit, and, while primarily designed for sporting wear, was the garment most worn “when travelling by coach, or carriage, or walking, and even in the house.” It was generally made out of heavy cloth, or of a velvet of a bright color, scarlet or red predominating.

With the change entering into costume generally after 1797, the masculine riding-habit of previous years gave way to a garment more in accord with the feminine fashions of the day (Fig. 77). Coats, waistcoats, and cocked hats were discarded, and in their place one finds a tight, short-waisted bodice with revers or lapels, and opened at the throat, a small ruching or lace frill edging the opening. The sleeves were tight from the shoulders to the wrists. The long skirt was not made very full. In place of the impractical and extravagant styles in hats, there came in a closefitting, brimless, black velvet cap.

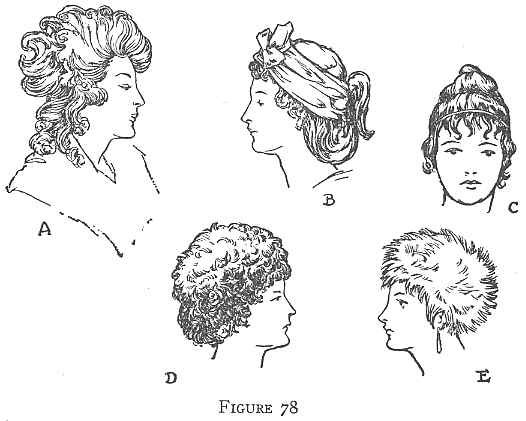

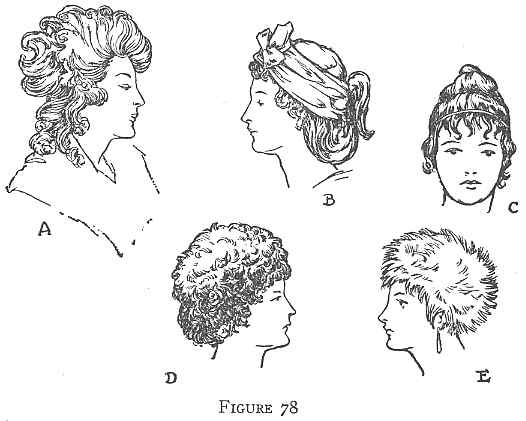

COIFFURES. – There was very little change in the manner of dressing the hair from that of the last period. After 1775, however, there was a tendency to widen and flatten the high-dressed coiffures at the top. We are told: “The front hair, gathered from the forehead, was pressed in a forward curve over a high pad, with one to three curls at the sides, and one at the shoulder, the back hair being arranged in a loose loop curled on the top and set with a large bow at the back” (Plate 62). The hair was covered with a white powder, powder reaching the height of its popularity just preceding and during the early years of the Revolution. It finally went out of favor about 1785. Extravagance in head-dresses in America never reached the absurd flights of fancy indulged in by the French; nor do they seem to have been generally popular, except for full dress or for special occasions. One reads more about them in the diaries and letters of fashionable young ladies, who loved to relate how they were tortured and tormented by having their heads made up, than one finds in actual evidence, judging from the portraits painted during those years. About 1781 the high towers for dress occasions were greatly lowered. At the same time the hair for everyday wear and general occasions was dressed in a new manner, with curls clustered over the head and with long flowing hair in the back. A curl often hung over one shoulder (Plate 64 B, Fig. 78 A). The hair was either powdered or left its natural color.

In 1797 a fashion for dressing the hair was introduced, as evidenced in many pictures and miniatures of that date. It was dressed with curls over the forehead and at the side of the face, and with the back hair looped low. It was then brought up to the crown of the head, where it was fastened by a ribbon or a comb, the free end being brought over in another loop or in a curl (Fig. 78 B).

Coming into fashion with the high-waisted French gowns of 1797 was a style wherein the hair was dressed in a most disheveled mode. The, back hair was brought up on the crown of the head in a mass of curls or in a twisted knot. From the center of the head, brought forward over the brow and cheeks, was a long, straggling bang or lock of hair (Fig. 78 C). Many colonial women, however, did not follow this absurd mode, but simply dressed their hair high in a knot, parting it in the center, and waving it back on both sides off the brow. Among the many exotic fashions of the Directory period in France, appearing in the last few years of the eighteenth century, and, from good evidence, followed by the women of America, was a style of dressing the hair “à la victime.” This entailed the sacrifice of having the hair cut off quite close to the scalp. It was then brushed out from the head to make it stand stiff and perpendicular, a few straggling locks being brought forward into the eyes (Fig. 78 E).

This style of dressing the hair may have come as a relief to many women of fashion, whose hair had been broken, scorched, and worn out in following the various modes of the tower head-dress. This mode was further supplemented by many women wearing wigs of short curly hair over their closely cropped heads – surely a temporary relief from all they had gone through at the hands of the barbers in following Dame Fashion (Fig. 78 D).

HATS AND CAPS. – It has already been noted in a previous chapter the tremendous increase in the variety and style of hats during the seventies. The mention made there of hats will serve for the first five years of this period.

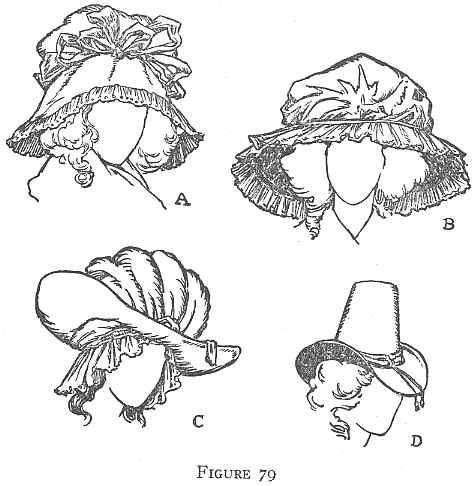

Fashion in hats was never more varied than it was during the eighties and to the middle of the nineties. Hats of all sizes and materials, from small hats, caps, and close shapes to large enveloping bonnets and great broad-brimmed hats. One finds hats of straw, beaver, felt, silk, and gauze. Through the introduction of a black lace called “grenadine” from Chantilly, a great stimulus was given to millinery during the years from 1775 to the close of the century. Many of these lace and gauze hats, made either with a crown or without, and in a variety of shapes, were such huge affairs that they fairly overbalanced the figure (Fig. 79 A B). In the course of two years, or from 1784 to 1786, the style of hats changed some seventeen times in the Paris fashion books, and the ladies in America who could afford to keep up with these fleeting fashions did so by importing much of their head-wear from abroad. A few of these styles are shown in Figures 79 A B C D.

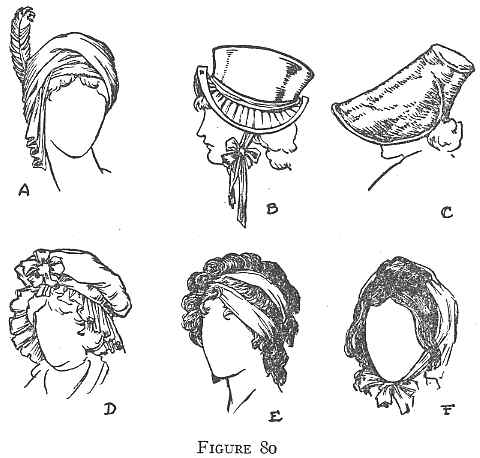

With the advent of the short-waisted gowns of 1795, 1797, and up to 1800, the vogue of the large hat passed. Fashion, however, kept changing with the same rapidity as formerly. Being so varied, it is impossible to treat comprehensively the subject of hats here. Material for the study of fashions in hats is very plentiful, and is available in all reference libraries in our large cities. It is only necessary to add that the turbanlike bonnets imported from France were particularly popular (Fig. 80 A)

Caps for morning and for house wear were still general. About 1780 one finds coming into fashion the large mob-cap made of gauze or net. It was full about the head, with a big bow in the front (PlateLXIII, Fig. 80 D).

From about 1797 on, a favorite fashion was to dress the hair with scarfs of gauze, bands of crêpe and silk, either plain or with a fringed edge, and with silk tasseled cords. Scarfs were braided and looped into the back hair, often enveloping the great knot of hair at the back (Fig. 80 F). Silk scarves, kerchiefs, and broad silk sashes were twisted around the head in form of a turban. Fillets were worn in the classic manner around the head, holding the hair in place; while in the back the loops of hair resting low on the neck were confined in silk nets. Pieces of ribbon were wrapped around and tucked into the hair, the hair being pulled through where the ribbon did not overlap (Fig. 80 E).

SHOES. – Shoes with high heels continued to be worn, but by 1775, heels, especially for general wear, began to be lowered. The toe was rounded. Until 1785 wide latchets were buckled over the instep. Then both latchets and buckles went out of style, and the pointed instep gave way to a low, rounded front. The heels were also considerably lowered. By 1790 the heel was a mere suggestion, and during the nineties practically vanished. With the disappearance of heels, buckles, and latchets, there came in the French Revolutionary fashion of fastening the shoes with ribbons about the ankles, in the manner of sandals.

ACCESSORIES. – Gloves, fans, parasols, muff, scarves, and jewels were all part of the fashionable attire of this period.