Contents

Contents

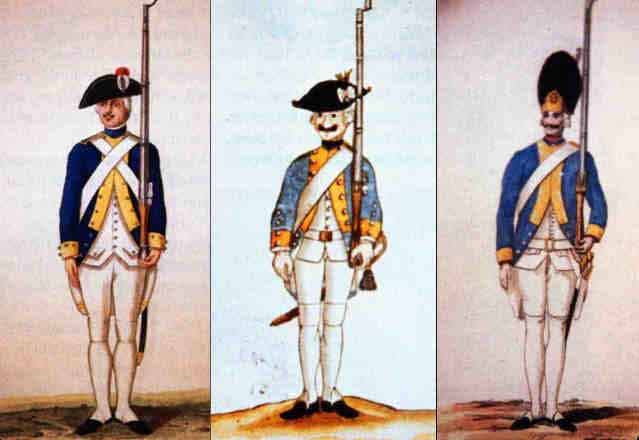

Germans helped win – and lose – the Battle of Yorktown, one of the key sites of the American Revolutionary War. Surprised? Don’t be. The unlucky Hessians, then in British pay, are quite familiar, but the Zweibruckeners, in French pay, are not. Blame it on the name: the Royal Deux-Ponts infantry is hardly the obvious place to look for German soldiers.

Some 200 years ago, the Royal Deux-Ponts recruited primarily in the lands of the Duke of Zweibrucken (which translates as two bridges, or deux ponts). These subjects of Duke Christian IV fought under the French name. This led generations of school children to believe that the only Germans in the Revolution were the subjects of Hesse’s Landgraf, who, eager to indulge in the good life at the Wilhelmshohe in Kassel, sold these men to the British to fight against the American patriots.

The Royal Deux-Ponts was an integral part of the Comte de Rochambeau’s expeditionary corps of almost 6,000 men, some accompanied by their wives and children. As they approached the New England coast in June 1780, Rochambeau’s fleet of some 43 warships and troop transports carried more than 1,000 Germans charged with waging war for American independence. These soldiers were under orders to fight, and, if necessary, to die for a country in which many of them would never even set foot. Ultimately, the transatlantic crossing cost the regiment more lives than the victory at Yorktown.

Firsthand accounts of the French fleet’s journey across the Atlantic are rare, particularly from enlisted men who lived below deck. But at least one soldier, Georg Daniel Flohr, kept a journal. The son of a butcher and a small farmer from Sarnstall, a suburb of Annweiler in the Duchy of Zweibrucken, Flohr had joined the regiment in June 1776, two months before his twentieth birthday. As the fleet set sail for America in April 1780, he began his diary, which he later expanded into his Account of the Travels in America which were made by the Honorable Regiment of Deux-Ponts on Water and on Land from the Years 1780 to 1784.

Acquired by the public library of (then German) Strasbourg sometime after 1871, this unique source slumbered on the shelves for almost a century before it was rediscovered in the 1970s by the amateur historian Rudolf Karl Tross. Reading the pages of Flohr’s journal is to experience the misery of the transatlantic crossing of the troops sent to aid the American rebels, as well as the vital, but almost forgotten, role played by the brave Zweibruckeners in the struggle for American independence.

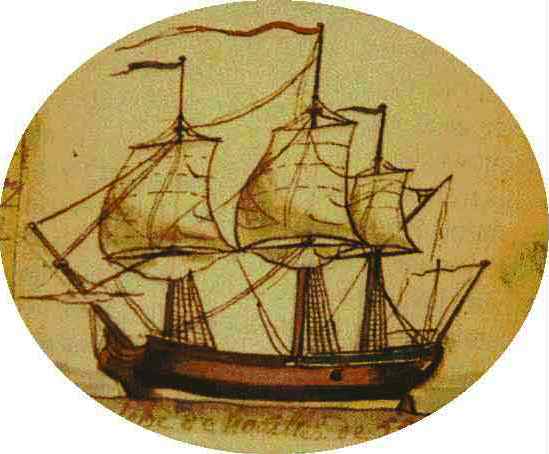

During April 1780, Rochambeau’s troops embarked at Brest. On May 2, the fleet set sail for the New World. Flohr reports in his journal that “around 2 o’clock after the noon hour we had already left the French coast behind and lost sight of the land. Now we saw nothing but sky and water and realized the omnipotence of God, into which we commended ourselves. Soon the majority among us wished that they had never in their born days chosen the life of a soldier and cursed the first recruiter who had engaged them. But this was just the beginning; the really miserable life was yet to start.”

Modern travelers may complain about the cramped conditions on an airplane, but what are a few hours on a DC9 or a 747 compared to the 70 days Flohr spent crossing the Atlantic on the Comtesse de Noailles ? At about 300 tons, she was no more than 95 feet long on the lower deck, maybe 30 feet wide, and a depth of about 12 feet in the hold. That is less cabin space than in a DC 9, which can carry almost the same number of passengers as Flohr’s ship: close to 350 men, 12 naval and 10 army officers and their domestics, plus a crew of about 45. Lodgings were tight and consisted of linen hammocks, described by Flohr as “not very comfortable.” Since two men had been assigned to a hammock, “the majority always had to lie on the bare floor.” Flohr concluded that: “He who wanted to lie well had better stayed home.”

Baron Ludwig von Closen, a captain in the Royal Deux-Ponts traveling on the ship with two servants, was rather more critical in his description of “this little tarry piece of bait.” Even the officers were ten to a cabin. At meals, 22 people squeezed into a chamber 15 feet long, 12 feet wide, and 4 1/2 feet high. Odors from “men as much as from dogs,” not to mention the cows, sheep, and chickens, “the perpetual annoyance from the close proximity” of fellow officers, and “the idea of being shut up in a very narrow little old ship, as in a state prison,” made for a “vexatious existence of an army officer…on these old tubs, so heartily detested by all who are not professional sailors.”

Derisive comments about airplane food are part and parcel of air travel, but the rank and file of Rochambeau’s army, lined up below deck for their rations, would have been happy to trade for some rubbery chicken. According to Flohr, “The food consisted of 36 Loth (a little over a pound) Zwieback (hardtack) daily, which was distributed in three installments: at 7 o’clock in the morning, at noon, and at 6 o’clock in the evening. Concerning meat, we received 16 Loth (about 1/2 a pound) per day, either salted bacon or beef, which was prepared every day for lunch. This meat, however, was salted so much that thirst was always greater than hunger. In the evenings we had to make do with a bad soup blended with oil and prepared from soybeans [called Schweinebohnen , or pig’s beans, by Flohr] and other such stuff. Anyone who has not yet seen it should just once take a look at this grimy mass and he too would lose al1 appetite.” With starvation the only other choice, the soldiers forced it down, living proof for Flohr of the proverb, “Hunger is a good cook.”

Their drink consisted of “1/2 Schoppen (1/4 liter) of good red wine, distributed in three rations; when it was brandy, half of that.” Of water there was “very little, mostly half a Schoppen per day.” This poor diet lacking in vitamins and minerals soon claimed its victims, and Flohr witnessed “daily our fellow brothers thrown into the depths of the ocean. No one was surprised though, since all our foodstuffs were rough and bad enough to destroy us.”

Even the serving of the food was not without its dangers. On February 2, 1783, while cruising off the coast of Curacao, fire broke out on board during the distribution of the brandy ration. The cooks had apparently done some extensive sampling and clumsily dropped a candle into the open barrel, which immediately burst into flames. “Flames shot out of the big hole underneath the middle mast, and you can easily imagine how we soldiers felt now. We quickly lost our appetite, threw our spoons away and did not look for them in three days. Wherever one looked, one saw and heard nothing but wailing and screams of ‘Maria and Joseph’ from the women who were on board. One soldier said to another, ‘I will not let myself burn to death,’ and I myself decided that I would rather jump into the water than burn alive, as drowning is an easier death than burning.”

Soldiers held onto ropes, ready to jump into the ocean if the fire should reach them. All seemed lost in the confusion. Worse still was “the ship’s captain and the officers not knowing how to give orders any more, that is how scared they were!” Fortunately, however, “there was a sailor on the ship, the worst of the whole lot, who arrived on the scene of the fire just as a cook wanted to turn over the barrel, which would have been our doom if it had happened. As soon as the sailor saw that, he immediately knocked the cook down so that the latter almost forgot to get up again, took a bag of Zwieback , threw it into the barrel, covered it with a canvas, and thus he suffocated the fire.”

Needless to say, all the Comtesse de Noailles passengers anxiously awaited their arrival in the New World. On July 11, the convoy finally sailed into Narragansett Bay. “We cast anchor and the city of Newport now lay before our eyes. It is adorned with a very beautiful Town Hall as well as a beautiful church tower. As soon as we cast our anchors, sloops from the town approached our ships in order to sell us their wares such as cherries, apples, pears, etc. The people in these sloops were all black, that is, moors. We, however, could not talk a word with them and neither could they talk to us, because their language is English.”

The troops debarking in Newport harbor were hardly combat-ready. Soldiers and sailors alike were afflicted with scurvy, and of companies 110 men strong, “barely 18-20 could still be used” to throw up defenses around the harbor. As the Newporters “could now daily see the misery of the many sick, of whom the majority could not even stand up and move…they had very great pity on them and did all they could for them.” Statistics tell a grim story: Flohr’s regiment lost only about a dozen men during the crossing, but by the time it went into winter quarters on November 1, 1780, the regiment was 73 short, victims of the difficult journey and the vitamin-deficient food served on board the French fleet. By way of comparison, the regiment lost only one-fourth that number in casualties in the storming of Redoubt #9 before Yorktown in October 1781, the bloodiest event of its campaign. Eighteen months later, April 1783, Flohr and his regiment departed from Santo Domingo for France.

This time, Flohr was on La Neptune together with a large number of parakeets, more than 40 monkeys, and assorted other living and stuffed-and-mounted creatures – souvenirs of almost three years in the New World. But Flohr did not mind his odd shipmates; he was looking forward “to seeing my fatherland again soon.” On the morning of June 17, La Neptune entered the harbor of Brest accompanied by shouts of “Vive le Roy.” On June 20, the Royal Deux-Ponts debarked. For the first five or six days, the rolling of the waves stayed with them. “We felt as if the whole ground was moving with us. If we looked at a hill or a tree, it seemed as if it was marching in front of us.” Flohr could “not give enough thanks to God” for his protection during the last three years. The next day, the regiment began its march through France to Landau, which they reached on September 4. Here Flohr served the remaining nine months until his discharge in the summer of 1784. From there he moved to Strasbourg and began work on his Reisenbeschreibung , which was completed in the summer of 1787.

Only once would Flohr again entrust himself to the ocean. In 1793 or 1794, then living in Paris, Flohr decided to shake the dust of the Old World off his feet and return to America. Ordained a Lutheran minister in 1802, he settled in Wytheville in western Virginia, where he died in 1826. In Virginia, St. John’s Lutheran Church has kept his memory alive, preserving his home and grave to this day.

But until the rediscovery of Flohr’s journal in Strasbourg, his military service had been unknown in his new land. Flohr never told his parishioners of his previous tour of duty in America. This helped obscure the identity of the Royal Deux-Ponts as a regiment of Germans fighting for American independence as well. In the summer of 1791, the Royal Deux-Ponts became the 99th Regiment of Infantry, and by the end of the First War of the Coalition there was hardly a German left in its ranks. As the decades passed, it became part of the body of “French” troops sent to fight in America. Today, the regimental standard of the 99ieme Regiment d’Infanterie stationed in Lyon proudly displays Yorktown among its days of glory, keeping the memory of the American Revolutionary War alive.