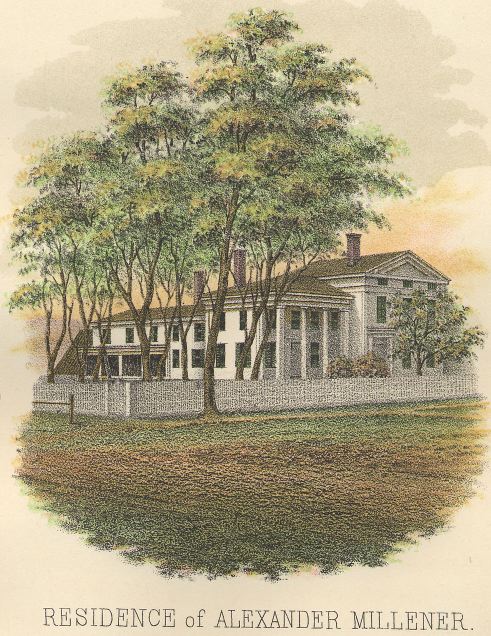

A few miles from Mr. Cook, at Adam’s Basin, on the Rochester and Niagara Falls division of the Central Railroad, lives ALEXANDER MILLINER, fourth of the survivors visited.

Mr. Milliner was born at Quebec on the 14th of March, 1760. His father was an English goldsmith, who came over with Wolfe’s army as an artificer, his wife accompanying him. At the scaling of the Heights of Abraham, he was detailed for special service, and at the close of the battle, lying down to drink at a spring on the plain, he never rose again; the cold water, in his heated and exhausted condition, causing instant death.

His widow remained a while at Quebec, where, as has been said, in the following spring Alexander was born.

While he was yet young, his mother, – whom her son describes as “‘English, high larnt, understood all languages, had been a teacher,” – removed with him to New York, where, becoming acquainted with a man by the name of Maroney, a well-to-do mason, she married him. This explains the circumstance of Mr. Milliner’s name appearing on the pension roll as “Alexander Maroney,” – his step-father, by whom, on account of his youth, he was enlisted, doing it under his own name. The enlistment, Mr. Milliner says, was at New York; though the record of the Pension Office gives it at Lake George. The pension roll, too, gives ninety-four years as Mr. Milliner’s age. This is manifestly an error of ten years; since the battle of Quebec, the fall before his birth, occurred on the 13th of September, 1759. On the 14th of March, of the present year, therefore, Mr. Milliner was one hundred and four years old.

Too young at the time of his enlistment for service in the ranks, he was enlisted as drummer boy; and in this capacity he served four years, in Washington’s Life Guard. He was a great favorite, he says, with the Commander-in-Chief, who used frequently, after the beating of the reveille, to come along and pat him on the head, and call him his boy. On one occasion, “a bitter cold morning,” he gave him a drink out of his flask. His recollection of Washington is distinct and vivid: “He was a good man, a beautiful man. He was always pleasant; never changed countenance, but wore the same in defeat and retreat as in victory.” Lady Washington, too, he recollects, on her visits to the camp. “She was a short, thick woman; very pleasant and kind. She used to visit the hospitals, was kind-hearted, and had a motherly care. One day the General had been out some time. When he came in, his wife asked him where he had been. He answered, laughing, ‘To look at my boys.’ ‘Well,’ said she, ‘I will go and see my children.’ When she returned, the General inquired, ‘What do you think of them?’ ‘I think,’ answered she, ‘that there are a good many.’ They took a great notion to me. One day the General sent for me to come up to headquarters. ‘Tell him,’ he sent word, ‘that he needn’t fetch his drum with him.’ I was glad of that. The Life Guard came out and paraded, and the roll was called. There was one Englishman, Bill Dorchester; the General said to him, ‘Come, Bill, play up this ‘ere Yorkshire tune.’ When he got through, the General told me to play. So I took the drum, overhauled her, braced her up, and played a tune. The General put his hand in his pocket and gave me three dollars; then one and another gave me more – so I made out well; in all, I got fifteen dollars. I was glad of it: my mother wanted some tea, and I got the poor old woman some.” His mother accompanied the army as washerwoman, for the sake of being near her boy.

He relates the following anecdote of General Washington: “We were going. along one day, slow march, and came to where the boys were jerking stones. ‘Halt’ came the command. ‘Now, boys,’ said the General, ‘I will show you how to jerk a stone.’ He beat ’em all. He smiled, but didn’t laugh out.”

Mr. Milliner was at the battles of White Plains, Brandywine, Saratoga, Monmouth, Yorktown, and some

others. The first of these he describes as “a nasty battle.” At Monmouth he received a flesh wound in his thigh. “One of the officers came along, and, looking at me, said, ‘What’s the matter with, you, boy?’ ‘Nothing,’ I answered. ‘Poor fellow,’ exclaimed he, ‘you are bleeding to death.’ I looked down; the blood was gushing out of me. The day was very warm. Lee did well; but Washington wasn’t very well pleased with him.” General Lee he describes as “a large man. He had a most enormous nose. One day a man met him and turned his nose away. ‘What do you do that for, you d –d rascal?’ exclaimed he. ‘I was afraid our noses would meet’, was his reply. He had a very large nose himself. Lee laughed and gave him a dollar.”

Of Burgoyne’s surrender he says, “The British soldiers looked down-hearted. When the order came to ‘ground arms,’ one of them exclaimed, with an oath, ‘You are not going to have my gun!’ and threw it violently on the ground, and smashed it. Arnold was a smart man; they didn’t sarve him quite straight.”

He was at the encampment at Valley Forge. “Lady Washington visited the army. She used thorns instead of pins on her clothes. The poor soldiers had bloody feet.” At Yorktown, he shook hands with Cornwallis. He describes him as “a fine looking man; very mild. The day after the surrender, the Life Guard came up. Cornwallis sat on an old bench. ‘Halt!’ he ordered; then looked at us – viewed us.”

Of the Indian warfare in the Mohawk valley, Mr. Milliner has broken recollections. Of the attack on Fort Stanwix, he gives the following graphic description: “The Indians burnt all before them. Our women came down in their shirt tails. The Indians got one of our young ones, stuck pine splinters into it, and set them on fire. They came down a good body of ’em. We had a smart engagement with ’em, and whipped ’em. One of ’em got up into a tree – a sharp-shooter. He killed our men when they went after water. The colonel see where he was, and says, ‘Draw up the twenty-four-pounder and load it with grape, canister, and ball.’ They did it. The Indians sat up in a crotch of the tree. They fired and shot the top of the tree off. The Indians gave a leap and a yell, and came down. Three brigades got there just in the nick of time. The Massachusetts Grenadiers and the Connecticut troops went forward, and the Indians fled.”

In all, Mr. Milliner served six years and a half in the army. The following is a copy of his pension certificate:

UNITED STATES of AMERICA – WAR DEPARTMENT

Pension Claims.]

This is to certify that Alexander Maroney, late a drummer in the Army of the Revolution, is inscribed on the Pension List Roll of the New York Agency, at the rate of eight dollars per mouth; to commence on the 19th day of September, 1819.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and affixed the seal of the War Department.

JOHN C. CALHOUN.

Besides his service the army, Mr. Milliner has served his country five years and a half in the navy. Three years of this service was on board the old frigate Constitution, he being in the action of February 20, 1814, in which she engaged the two British ships, the Cyane and the Levant, capturing them both. While following the sea he was captured by the French and carried into Guadaloupe. As prisoner there, he suffered hard treatment. Of the bread which he says he has eaten in seven kingdoms, he pronounces that in the French prison decidedly the worst.

He still has the little tin case, in which in the old days of British seizure and search, he used to carry his protection papers. The papers themselves are lost.

At the age of thirty-nine, Mr. Milliner married Abagail Barton, aged eighteen; and, settled in Cortlandt county, New York. To my inquiry, how he came to settle there, his reply was, “O, I kind o’ wandered round.” For sixty-two years he and his wife lived together, without a death in the family or a coffin in the house. His wife died two years ago. They had nine children, seven of whom are now living. The oldest was born in 1800. He has also forty-three grandchildren, seventeen great-grandchildren, and three great-great-grand-children. At the time of his wife’s death, Mr. Milliner was still able to cultivate his garden; his age being one hundred and two years.

Mr. Milliner’s occupation since he settled down in life has been that of farming. His temperament has ever been free, happy, jovial, careless; and to this, doubtless, is largely owing the extreme prolongation of his life. He has been throughout life full of jokes; in the army he was the life of the camp; could dance and sing, and has always taken the world easily, “nothing troubling him over five minutes at a time,” care finding it impossible to fasten itself upon him, and so, after trial, letting him alone. His spirits have always been buoyant, nothing depressing him.

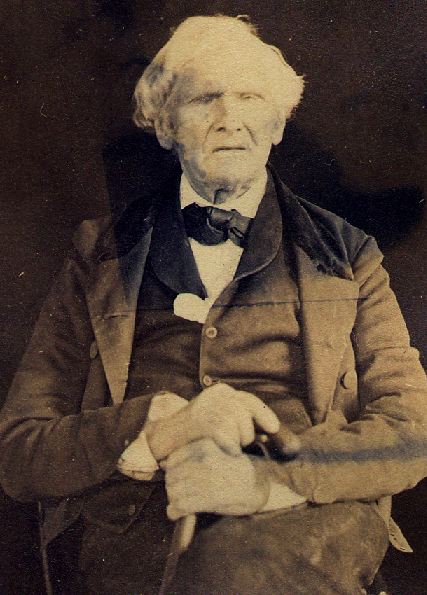

Mention has been made of his wound at the battle of Monmouth. At another time a bullet passed through the head of his drum. At the time his photograph was taken he could still handle his drum, playing for the artist with excellent time and flourishes which showed him to have been a master of the art. He sang also, in a clear voice, several songs, both amorous and warlike; singing half a dozen verses successively, giving correctly both the words and the tune.

”His sight is as good yet as when young. He reads his Bible every day without the aid of glasses. His memory is clear respecting events which ocurred eighty or ninety years ago; though he finds difficulty in giving long, connected accounts.

In size, he is small, more so than his picture would indicate. Though never robust, his health has always been good. This has not been from any special carefulness in his habits – in which he has been careless

– rather giving himself and his health no thought. He uses tea and coffee, and still takes regularly his dram. His home is at present with his son, Hon. I. P. Milliner, of Adam’s Basin. His every wish is gratified, so far as is compatible with his welfare; and even when this is forbidden, still there is no necessity of denying him, since his wish, when expressed and nominally assented to, is at once forgotten by him; and if he is not reminded of it, is never thought of again.

In the present conflict with treason, Mr. Milliner’s sympathies, as with all his surviving Revolutionary comrades, are enlisted most strongly on the side of the Union; he declares that it is “too bad that this country, so hardly got, should be destroyed by its own people.” He inquires every day or two about the army; and expresses the desire to live to see the rebellion crushed. At the outbreak of it, he wanted to take his drum and go down to Rochester, and beat for volunteers. Two years ago, in September, he presided over a meeting for raising recruits for the One Hundred and Fortieth New York Regiment. His presence at the meeting, it is said, caused great excitement and enthusiasm.

Upon his last birthday (his one hundred and fourth), the Pioneers of Monroe county – a veteran association whose headquarters are at Rochester – went out in a body to Adam’s Basin, to pay their respects to their aged associate. Arrived at the Basin, and marching in procession to the house where the old man resides, he appeared upon the steps, and was greeted with cheers. After many had shaken hands with him, the procession was re-formed, the old man heading it, and marched to the church, where, after the singing of Washington’s Funeral Hymn by the Pioneers and a short historical address, Mr. Milliner stood up on a seat where all could see him, and thanking them for their kind attention, appealed to them all to be true to their country, saying that he had seen “worse looking visages than his own hung up by the neck.” Since that time, his health has rapidly failed; and it is now unlikely that he will live to see another birthday.