Leutze painted “Washington Rallying the Troops at Monmouth” about a year after he painted Washington Crossing the Delaware to which it is comparable in size – about 23 feet by 13 feet. The work was the result of a commission from David Leavitt of New York City. Upon its arrival in New York from Dusseldorf in 1854, it was put on public display for several months. Mrs. Mark Hopkins, widow of the western railroad mogul, purchased it in 1879. In 1882 she made a gift of it to the University of California, where it was exhibited for many years before dropping out of sight around the turn of the century. In 1857 Leutze made a copy, one-third the size of the original, which came into the possession of the Monmouth (New Jersey) County Historical Association and exhibited in their offices in Freehold, New Jersey. In time, this copy came to be accepted as the one and only original.

In the early 1960s, Dr. Raymond L. Stehle, who was writing a biography of Leutze, mentioned in a Pennsylvania History journal article that Leutze had painted a companion piece which had been almost completely forgotten. According to Dr. Stehle, this companion work had been given to the University of California campus at Berkeley, late in the nineteenth century, but had not been exhibited for over fifty years.

Dr. Stehle’s mention triggered a search for the “Lost Leutze”, and Herschel Chipp, who was at that time curator of the University of California’s various art collections, examined his inventory of artwork that had been put into storage, and lo and behold! Leutze’s “Washington at Monmouth” was on his list. With this information, it wasn’t long before the trail led to a large wooden box in a storage room in the basement of the women’s gymnasium.

“We were very apprehensive as we started to unroll it,” Dr. Chipp said in an interview at the time, “since it had been stored a very long time, and its condition was extremely uncertain. But as more and more of the picture appeared on the floor we were at first pleased, then astounded at what we saw. The more of it appeared, the more brilliant and dramatic it became.”

The University of California lost no time sending news releases about the picture to newspapers and magazines across the country, and the Chancellor of the University announced a special exhibition in honor of Washington’s Birthday. A San Francisco critic promptly attacked the work as unhistorical, utterly outmoded in style, and distinctly not part of “our usable past.” A University of California art professor came to the painting’s defense, arguing that the opus, “although not a historical document for the battle of 1778, is a document for the taste of the time” – that is, Leutze’s time – and “a rich but ordered composition.”

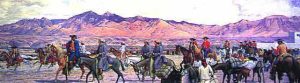

Washington at Monmouth is a stark counterpoint to the almost pensive figure of the Great General shown in “Washington Crossing the Delaware” The former work is Leutze working in the full-blown drama of the 18th century Romantic School – Washington astride a charging courser which has its nostrils flared, flashing saber aloft, from head to toe the larger than life hero. The instant that Leutze dramatized on this canvas was in legend the one time in Washington’s life when he was angry enough to lose his temper and use foul language in public.

The scene was occasioned by the failure on the part of Major General Charles Lee to follow up on an advantage that had been gained over the British force of Sir Henry Clinton as they withdrew from Philadelphia to New York. Lee was commander of a large advance force that made contact with the enemy’s rear guard, but then, for reasons never clearly explained, ordered his troops to retreat when he had the advantage over his foe. The British counterattacked smartly, and what might have been a triumph for the Americans almost turned into a rout.

It was at this juncture that Washington, who had been leading the main force of the Americans behind Lee, became aware of what was happening. “After marching five miles,” said Washington’s after-action report to Congress, “to my great surprise and mortification, I met the whole advanced corps retreating, and, as I was told, by General Lee’s orders, without having made any opposition, except one fire…” Soon afterward Washington encountered Lee near Monmouth Court House (now Freehold, New Jersey.) Washington was livid in demanding an explanation, punctuating his questioning with imprecations which were variously reported by several members of his staff. Alexander Hamilton, then Washington’s Aide-De-Camp, described it as “an awful adjuration”; the Marquis de Lafayette, many years later, said that Washington called Lee “a damned poltroon”; and Lee himself, in a letter of complaint, used the phrase “very singular expressions.” And Brigadier General Charles Scott, whose movements on the battlefield may have been partly responsible for Lee’s actions, went even further. Years later he was asked if he had ever heard Washington swear. “Yes sir, he did once,” Scott replied. “It was at Monmouth and on a day that would have made any man swear. Charming! Delightful! Never have I enjoyed such swearing before or since. Sir, on that memorable day he swore like an angel from heaven!” There is a slight problem with Scott’s account, though – according to reliable sources, he was nowhere near the scene when Washington confronted Lee.

Washington almost immediately thereafter galloped to the rear of the retreating American column, rallying officers and ordering them to make a stand along a hedgerow on the brow of a hill. Washington also had his artillery put into position to fend off the counterattacking British cavalry. Despite the incredible heat (many men on both sides were collapsing from exhaustion and thirst) the Americans drove off several enemy assaults. The day ended in an honorable draw. Honorable, that is, to all except Charles Lee, who was court-martialled and relieved of his command.

Washington at Monmouth, like Washington Crossing the Delaware, is a work that can be seen again and again without noticing everything. Leutze took great pains to be meticulously accurate with regard to uniforms, weapons, facial types of the soldiers, and portraits of the leading figures. The composition is carefully balanced, but packed with action. In the center, Washington has sunlight shining on his wrathful face, waving his sword as he rallies the troops of Lee’s command. Hamilton and a bareheaded Lafayette have ridden up with him and are reining in their horses. The figure of Lee is shrinking back in his saddle, his crestfallen face in shadow. In the foreground, exhausted riflemen and a thirsty dog scoop water from a spring; farther back, on the left, the soldiers raise a cheer for their Commander in Chief, while some of them have already turned to fire on the British. On the hilltop, behind the figure of Washington, American artillery gallops into position to stem the British attack, and at far right the men of Washington’s command approach the scene to enter the battle.

Washington at Monmouth, while it makes some historical errors (the General’s horse, for instance, was actually white), is true in spirit to the verifiable records of the Battle of Monmouth. Beyond that, it movingly captures a moment in time when George Washington was exercising his truly heroic qualities in the American cause, and we are content to echo Hamilton’s comment on the occasion itself: “I never saw the General to so much advantage.”