Contents

Contents

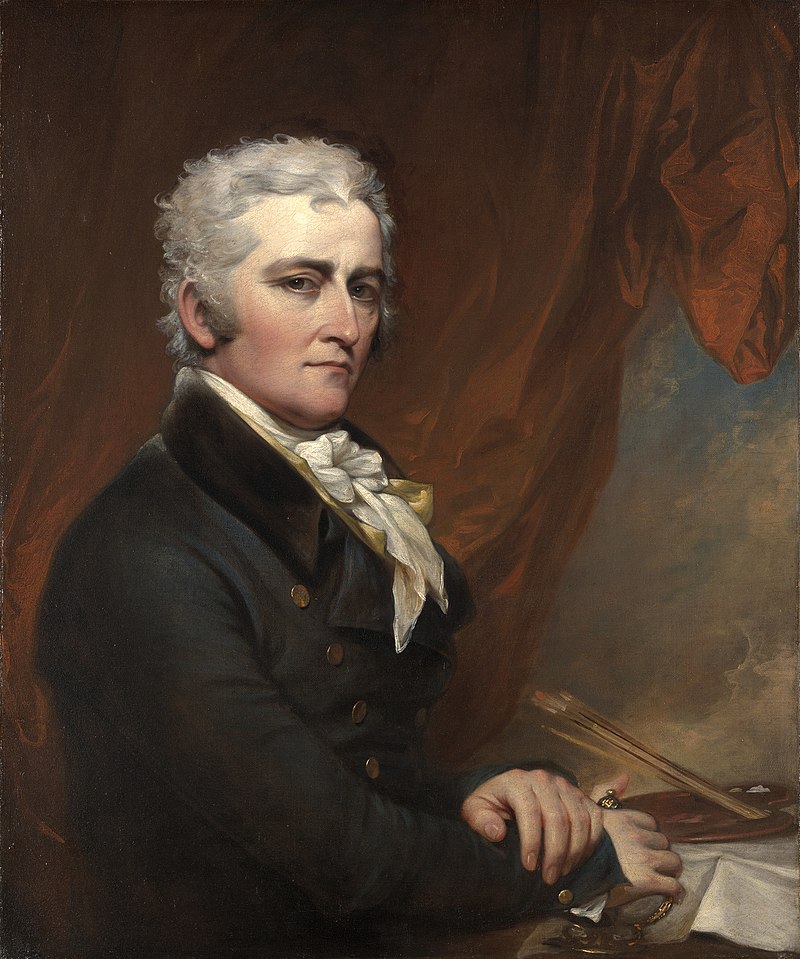

Born in Lebanon Connecticut on June 6 1756, John Trumbull was the son of Jonathan Trumbull, the only colonial Royal Governor to embrace the patriot cause. His mother was Faith Robinson, a descendant of Pilgrim leader John Robinson. He was also the first American painter to have a college education, being a graduate of Harvard, entering the class of 1773 in the Junior Year at age fifteen.

His father wanted him to pursue either the ministry or law, feeling that the manual crafts were beneath the family dignity, but once at Harvard, he lost no time making the acquaintance of John Singleton Copley, the leading portrait painter in the Colonies. His own account of his introduction is as follows: “We found Mr. Copley dressed to receive a party of friends at dinner. I remember his dress and appearance – an elegant looking man, dressed in a fine maroon cloth, with gilt buttons – this was dazzling to my unpracticed eye!-but his paintings, the first I had ever seen deserving the name, riveted, absorbed my attention, and renewed all my desire to enter upon such a pursuit.”

After graduation, Trumbull taught school for a winter in Lebanon, but continued his study of painting, much to his father’s chagrin.

At the outbreak of the Revolution, Trumbull marched to Boston under the command of Gen. Joseph Spencer, as Adjutant of the 1st Connecticut Regiment. Stationed at Roxbury, he witnessed the Battle of Bunkers Hill from there, which was the closest he ever came to any of the subjects of his great historical paintings. He came to the attention of General Washington by drawing a plan of the enemies works in front of the Revolutionary Army on Boston Neck, and was shortly thereafter appointed his Aide-de-Camp (General Order of July 27, 1775). In June of 1776, upon the assumption by General Gates of the command of the Army in the Northern Department, Trumbull was appointed his Adjutant. After service at Crown Point and Ticonderoga, he resigned on February 22, 1777, ostensibly because his commission as a Colonel was dated some three months later than his appointment to that rank by General Gates.

Trumbull moved to Boston and hired as a studio the painting room built by artist John Smibert. He found still there “several copies by him from celebrated pictures in Europe, which were very useful to me.” With the exception of a short term of service as volunteer Aide-de-Camp to General Sullivan in Rhode Island, Trumbull remained in Boston until the autumn of 1779 when he determined to go to England to study under Benjamin West, one of the leading painters in Europe and official Painter of Historical Subjects to George III.

Trumbull reached London in July of 1780 and presented to West a letter of introduction from Benjamin Franklin. He began work immediately, occupying a painting room with Gilbert Stuart, who was also a student under West at the time.

Trumbull was arrested on November 18, l780, and threatened with hanging as an American spy, in retaliation for the hanging of Major Andre, the British spy who conspired with Benedict Arnold. He was incarcerated until June, 1781, when West and Copley interceded with the king, and he was released upon condition that he leave the kingdom.

Trumbull returned to London in 1784 to complete his studies under West and attend classes at the Royal Academy, and the influence of West can be clearly seen during this period. West himself desired to do a historical series on the American Revolution, but feared loss of Royal Patronage, and Trumbull began to: “meditate seriously the subjects of national history, of events of the Revolution, which have since been the great objects of my professional life.” Trumbull’s ambition, tempered as it was by West’s influence, finally crystallized into a determination to become the painter of the American Revolution, and several of his historical paintings were begun and two finished in West’s studio, the Battle of Bunkers Hill being completed there in 1786.

Meeting Thomas Jefferson in London in the summer of 1785, upon his invitation Trumbull later visited Paris, and there submitted to him his two finished paintings, “The Battle of Bunkers Hill” and “The Death of General Montgomery at Quebec,” and both Jefferson and John Adams, then Minister to Great Britain, counseled with Trumbull and assisted him in selecting ten additional events to be painted. Of this number Trumbull completed eight, and these are now in the possession of Yale University.

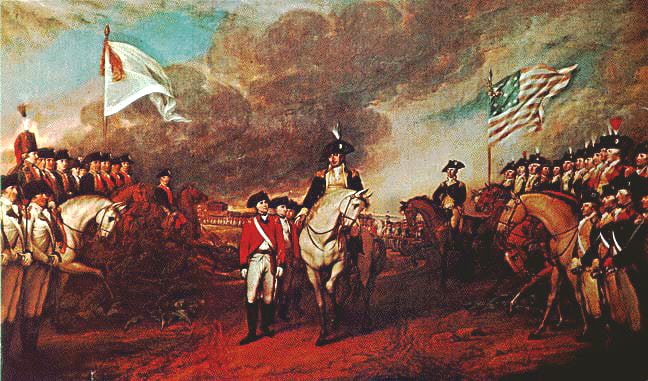

The sketch for “The Declaration of Independence” was made at Jefferson’s house in the Grille de Chaillot in 1786 with the assistance of his “information and advice.” Returning to London, Trumbull completed the composition of “The Declaration of Independence,” “The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis,” ‘The Battle of Trenton,” and “The Battle of Princeton” while in West’s studio. He left out the heads, however, which were to be filled in from life as the chance might be afforded. Thus, the head of John Adams was painted into “The Declaration of Independence” in London in the summer of 1787, Trumbull saying that just before Adams left the Court of St. James’s he: “had the powder combed out of his hair. Its color and natural curl were beautiful, and I took that opportunity to paint his portrait in the small Declaration of Independence”.

In the autumn he again visited Jefferson and there painted his portrait into the same canvas, and the portraits of the French officers in “The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis” “were painted from life in Mr. Jefferson’s house.” Apparently he also left certain details in the backgrounds to be finished later from sketches made on the spot.

As Congress was to assemble in New York in December of 1789, Trumbull went there to pursue his work. He also hoped to sell engravings of his historical paintings, but that project failed. While there he had sittings from Washington, and likewise painted the portraits of many distinguished characters into several of the canvases, and later he traveled throughout the country on the same errand. In addition he painted many small portraits as pencil sketches or oil on mahogany to be used in the scenes determined upon but not yet designed. Yale possesses fifty-eight miniature portraits, most of which were painted with this end in view. He also visited and sketched historic places so that he might become familiar with the actual setting of the events he was depicting.

During these years (1789-1794) Trumbull lived, for the most part, in the new nation’s capitol, New York City (some believe because Gilbert Stuart had taken up residence in Boston), supporting himself by painting portraits while seeking in vain to obtain the financial backing of the Government for his project. The portraits of this period, when Trumbull was fresh from six years’ study abroad, at least three of which were passed under the instruction of West, are considered his best work and rank equally with examples of any American painter of the time. He is known for fluid brushstrokes and subtle glazes, and also produced a very few landscapes that anticipate the Hudson River School.

Failing to obtain Government support, Trumbull accompanied John Jay to London in May, 1794, and acted as his secretary while he was negotiating what became known as “Jay’s Treaty.” In 1796 he was appointed one of the commissioners to carry out one of the Articles of that Treaty; and remained about eight years in London engaged in this work.

Trumbull returned to New York in 1804 and sought to rebuild his practice as a portrait painter, but his ten years of foreign service, during which time he seldom exercised his talent, seem to have robbed his hand of much of its ability. Very few of the portraits of this period (1804-l808) evidence his earlier talent. Trumbull attributed his lack of success to the embargo placed by President Jefferson in the autumn of 1808 on all commerce, which he says threatened “the prosperity of those friends from whom I derived my subsistence,” but it almost seems as if his genius had flared for a few brief years and then gone out forever, so marked is the division between the work of his youth and that of later life. In any event, he once more went abroad in 1809, and was stuck in England by the outbreak of the War of 1812, and forced to remain there until August of 1815.

The Capitol at Washington having been partially destroyed by the British in 1814, Trumbull saw the opportunity in its restoration of realizing his ambition, and he applied for the commission to decorate the Rotunda with enlargements from his small originals. For this purpose several of the canvases were exhibited in the House of Representatives in 1816 and as a result, a resolution passed both houses of Congress to employ Trumbull to execute four paintings: “Commemorative of the most important events of the American Revolution, to be placed, when finished, in the Capitol of the United States.” Trumbull wrote Jefferson on December 26, 1816: “The Declaration of Independence is finished – Trenton Princeton and York Town which were long since finished & engraved – I shall take them all with me to the Seat of Government. in a few days that I may not merely talk of what I will do but show what I have done.”

The choice of the subjects and the size of the paintings, were left to the President. Trumbull tells of his interview with Madison, in which the President first suggested the Battle of Bunkers Hill as one subject, but as only four of his paintings had been ordered, he recommended “The Surrender of General Burgoyne,” “The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis,” “The Declaration of Independence,” and “The Resignation of Washington.” These were finally selected by President Madison and Trumbull was engaged for the sum of $32,000 to enlarge them to a size of eighteen feet by twelve feet, with life-size figures.

Trumbull first enlarged “The Declaration of Independence” and, when finished, exhibited it during the years 1818-20 in several cities of the United States with great success.

Dunlap, in the first book on the subject of American Art, says of this painting: “Public expectation was perhaps never raised so high respecting a picture, as in this case; and although the painter had only to copy his own beautiful original of former days, a disappointment was felt and loudly expressed. Faults which escaped detection in the miniature, were glaring when magnified – the tone and the coloring were not there – attitudes which appeared constrained in the original, were awkward in the copy – many of the likenesses had vanished.” On September 1, 1818, John Quincy Adams wrote in his diary “Called about eleven o’clock at Mr. Trumbull’s house, and saw his picture of the Declaration of Independence, which is now nearly finished. I cannot say I was disappointed in the execution of it, because my expectations were very low; . . . I think the old small picture far superior to this large new one.”

“Surrender of Cornwallis” was enlarged next and in turn was exhibited in New York, Boston, and Baltimore in 1820.

“The Surrender of General Burgoyne” and “The Resignation of Washington” were enlarged from compositions painted at about this time, and the four enlargements were installed in the Rotunda of the Capitol in Washington under Trumbull’s supervision in 1824.

In regard to the criticisms, the truth is that Trumbull was a first-class painter in miniature. His small portraits are in oil on canvas or on wood, and his work in this field is excelled only by some of the miniatures by Malbone, and equaled only by the best work of Fraser and Trott (Dunlap says: “The pictures of the Battle of Trenton and Princeton, are among the most admirable miniatures in oil that ever were painted. The same may be said of the portraits in the small picture of the “Surrender of Cornwallis”…”). Some of his life-size portraits done before 1794 (when he left painting for diplomacy) will stand the severest test, but when, however, in 1816, at the age of sixty, he undertook to enlarge his small originals, twenty by thirty inches, to a size twelve by eighteen feet, the result bears silent witness to the fact that he had had no training in this branch of art and for twenty years before he had been at best an unsuccessful painter.

It must be borne in mind also that the criticisms of Dunlap and other writers are solely directed at the enlargements and all agree on the beauty and value of the small canvases. It should also be mentioned that Trumbull lost the sight of one eye in childhood, and the concomitant lack of depth perception exaggerated by advancing age may, to some extent, explain the “flat” look of the enlargements.

The paintings in Washington cannot be used, therefore, as fair examples of the art of John Trumbull, but his reputation must stand upon the original compositions. The importance of the canvases and miniatures lies in the fact that they are original portraits from life and are the work of Trumbull’s early and brilliant youth and in a field in which he excelled, while the enlargements therefrom are the work of his declining years.

Trumbull attempted in vain to induce the Government to commission him to fill the remaining panels of the Rotunda. and failing thus to sell his collection of Revolutionary portraits to the nation, his impaired health and failing powers brought him onto bad times, wherein at last he sought another way by which to use his early work to furnish support for his old age.

Trumbull tells us, in his Reminiscences, the pathetic story of how, when funds began to diminish, he was forced to sell “scraps of furniture, fragments of plate, etc.,” and of how many pictures remained on his hands unsold, and to all appearance unsaleable. It occurred to him that although “the hope of a sale to the nation, or to a state, became more and more desperate from day to day,” yet some private institution might be willing to possess the paintings, making payment therefor by a life annuity. He first considered his alma mater, Harvard, but finally chose Yale, as it was within his native state and relatively poor, for Trumbull, throughout his life, appreciated the importance of his Revolutionary portraits and never wavered from the conviction that someday their great historic value would be recognized, and he believed that their exhibition would be a source of revenue to the College. The matter was suggested to the Trustees of Yale College by a friend, and a contract, dated December 19, 1831 was signed, by which Trumbull, in consideration of an annuity of $1,000, in addition to the miniature portraits of persons distinguished during the Revolution, and certain copies of old masters, deeded to Yale:

“Eight original paintings of subjects from the American Revolution, viz.,

- The Battle of Bunker’s Hill.

- The Death of General Montgomery at Quebec.

- The Declaration of Independence.

- The Battle of Trenton.

- The Battle of Princeton.

- The Surrender of General Burgoyne.

- The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis.

- Washington resigning his Commission.”

Yale bound itself to erect a fireproof building for the reception of the paintings, of such form and dimensions as Trumbull should approve, and after the paintings were arranged that they should be exhibited and the profits first applied to the payment of the annuity, and all the profits after his death perpetually appropriated towards defraying the expenses of educating poor scholars in Yale College.

Trumbull afterward superintended the building of the Trumbull Gallery, which stood upon the Yale Campus until the year 1901. He made, later, several additions, so that the Gallery in 1841, when he wrote his Reminiscences, contained, in addition to the miniatures: “fifty-five pictures by my own hand, painted at various periods, from my earliest essay of the “Battle of Cannae,” to my last composition, the “Deluge,” including the eight small original pictures of the American Revolution, which contain the portraits painted from life.” Today, the only remaining example of his architectural talent is the Meeting House in Lebanon, Connecticut (circa 1804-6)

It is true that Trumbull chose to depict in “The Battle of Bunker’s Hill” and in “The Death of General Montgomery at Quebec,” the success of our foes, and in regard to “Bunker’s Hill” he is said to have adopted the British rather than the American account of the battle. At the same time, these canvases contain portraits from life painted by one of the first painters of the age, a man who had served in the Revolution and who was familiar with the scenes of action. Trumbull in writing to Jefferson of his qualifications to paint the scenes of the Revolution, quite rightly stated that: “some superiority also arose from my having borne personally a humble part in the great events I was to describe. No one lives with me possessing this advantage, and no one can come after me to divide the honor of truth and authenticity, however easily I may hereafter be exceeded in elegance.” (Letter to Jefferson, June 11, 1789).

It is fair to state that most of the people of the United States think of the Battle of Bunker’s Hill and the Declaration of Independence only in terms of Trumbull’s compositions, so universal has been their use to depict these events in our history.

Thanks to Trumbull, nowhere else can be found likenesses of many of the actors in these scenes, and nowhere else can be found together so many original portraits of persons prominent in the Revolution. For the student of American history who seeks to learn what manner of men these were, the Trumbull canvases and miniatures, containing about two hundred and fifty portraits, are the most important source of original information that exists.

Trumbull died in 1843, and was interred on the Yale Campus under the building which contained so much of the important work of his long life, covering a span of eighty-eight years.

The inscription over his tomb ends with these lines:

To his Country he gave his

SWORD and his PENCIL