Contents

Contents

Esther De Berdt was born in the city of London, on the 22d of October, 1746, (N. S.,) and died at Philadelphia on the 18th of September, 1780. Her thirty-four years of life were adorned by no adventurous heroism; but were thickly studded with the brighter beauties of feminine endurance, uncomplaining self-sacrifice, and familiar virtue – under trials, too, of which civil war is so fruitful. She was an only daughter. Her father, Dennis De Berdt, was a British merchant, largely interested in colonial trade. He was a man of high character. Descended from the Huguenots, or French Flemings, who came to England on the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, Mr. De Berdt’s pure and rather austere religious sentiments and practice were worthy of the source whence they came. His family were educated according to the strictest rule of the evangelical piety of their day – the day when devotion, frozen out of high places, found refuge in humble dissenting chapels – the day of Wesley and of Whitfield. Miss De Berdt’s youth was trained religiously; and she was to the end of life true to the principles of her education. The simple devotion she had learned from an aged father’s lips, alleviated the trials of youth, and brightened around her early grave.

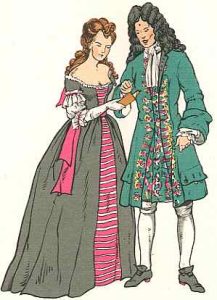

Mr. De Berdt’s house in London, owing to his business relations with the Colonies, was the home of many young Americans who at that time were attracted by pleasure or duty to the imperial metropolis. Among these visitors, in or about the year 1763, was Joseph Reed, of New Jersey, who had come to London to finish his professional studies (such being the fashion of the times) at the Temple. Mr. Reed was in the twenty-third year of his age – a man of education, intelligence, and accomplishment. The intimacy, thus accidentally begun, soon produced its natural fruits; and an engagement, at first secret, and afterwards avowed, was formed between the young English girl and the American stranger. Parental discouragement, so wise that even youthful impetuosity could find no fault with it, was entirely inadequate to break a connection thus formed. They loved long and faithfully – how faithfully, the reader will best judge when he learns that a separation of five years of deferred hope, with the Atlantic between them, never gave rise to a wandering wish, or hope, or thought.

Mr. Reed, having finished his studies, returned to America in the early part of 1765, and began the practice of the law in his native village of Trenton. His success was immediate and great. But there was a distracting element at work in his heart, which prevented him from looking on success with complacency; and one plan after another was suggested by which he might be enabled to return and settle in Great Britain. That his young and gentle mistress should follow him to America, was a vision too wild even for a sanguine lover. Every hope was directed back to England; and the correspondence, the love letters of five long years, are filled with plans by which these cherished but delusive wishes were to be consummated. How dimly was the future seen!

Miss De Berdt’s engagement with her American lover was coincident with that dreary period of British history, when a monarch and his ministers were laboring hard to tear from its socket, and cast away for ever, the brightest jewel of the imperial crown – American colonial power. It was the interval when Chatham’s voice was powerless to arouse the Nation, and make Parliament pause, when penny-wise politicians, in the happy phrase of the day, “teased America into resistance;” and the varied vexations of stamp acts; and revenue bills, and tea duties, the congenial fruits of poor statesmanship, were the means by which a great catastrophe was hurried onward.

Mr. De Berdt’s relations with the Government were, in some respects, direct and intimate. His house was a place of counsel for those who sought, by moderate and constitutional means, to stay the hand of misgovernment and oppression. He was the Agent of the Stamp Act Congress first, and of the Colonies of Delaware and Massachusetts afterwards. And most gallantly did the brave old man discharge the duty which his American constituents confided to him. His heart was in his trust; and we may well imagine the alternations of feeling which throbbed in the bosom of his daughter, as she shared in the consultations of this almost American household; and according to the fitful changes of time and opinion, counted the chances of discord that might be fatal to her peace, or of honorable pacification which should bring her lover home to her. Miss De Berdt’s letters, now in the possession of her descendants, are full of allusions to this varying state of things, and are remarkable for the sagacious good sense which they develop. She is, from first to last, a stout American. Describing a visit to the House of Commons, in April, 1766, her enthusiasm for Mr. Pitt is unbounded, while she does not disguise her repugnance to George Grenville and Wedderburn, whom she says she cannot bear, because “they are such enemies to America.” So it is throughout, in every line she writes, in every word she utters; and thus was she, unconsciously, receiving that training which in the end was to fit her for an American patriot’s wife.

Onward, however, step by step, the Monarch and his Ministry – he, if possible, more infatuated than they – advanced in the career of tyrannical folly. Remonstrance was vain. They could not be persuaded that it would ever become resistance. In 1769 and 1770, the crisis was almost reached. Five years of folly had done it all. In the former of these years, the lovers were re-united, Mr. Reed returning on an uncertain visit to England. He found everything but her faithful affection changed. Political disturbance had had its usual train of commercial disaster; and Mr. De Berdt had not only become bankrupt, but unable to rally on such a reverse in old age, had sunk into his grave. All was ruin and confusion; and on the 31st of May, 1770, Esther De Berdt became an American wife, the wedding being privately solemnized at St. Luke’s Church, in the city of London.

In October, the young couple sailed for America, arriving at Philadelphia in November, 1770. Mr. Reed immediately changed his residence from Trenton to Philadelphia, where he continued to live. Mrs. Reed’s correspondence with her brother and friends in England, during the next five years, has not been preserved. It would have been interesting, as showing the impressions made on an intelligent mind by the primitive state of society and modes of life in these wild Colonies, some eighty years ago, when Philadelphia was but a large village – when the best people lived in Front street, or on the water side, and an Indian frontier was within a hundred miles of the Schuylkill. They are, however, all lost. The influence of Mrs. Reed’s foreign connection can be traced only in the interesting correspondence between her husband and Lord Dartmouth, during the years 1774 and 1775, which has been recently given to the public, and which narrates, in the most genuine and trustworthy form, the progress of colonial discontent in the period immediately anterior to actual revolution. In all the initiatory measures of peaceful resistance, Mr. Reed, as is well known, took a large and active share; and in all he did, he had his young wife’s ardent sympathy. The English girl had grown at once into the American matron.

Philadelphia was then the heart of the nation. It beat generously and boldly when the news of Lexington and Bunker Hill startled the whole land. Volunteer troops were raised – money in large sums was remitted, much through Mr. Reed’s direct agency, for the relief of the sufferers in New England. At last, a new and controlling incident here occurred. It was in Philadelphia that, walking in the State House yard, John Adams first suggested Washington as the National commander-in-chief; and from Philadelphia that in June, 1775, Washington set out, accompanied by the best citizens of the liberal party, to enter on his duties.

As this memoir was in preparation, the writer’s eye was attracted by a notice of the Philadelphia obsequies of John Q. Adams, in March,1848. It is from the New York Courier and Enquirer:

“That part of the ceremonial which was most striking, more impressive than anything I have ever seen, was the approach through the old State House yard to Independence Hall. I have stood by Napoleon’s dramatic mausoleum in the Invalides, and mused over the more simple tomb of Nelson, lying by the side of Collingwood, in the crypt of St. Paul’s; but no impression was made like that of yesterday. The multitude – for the crowd had grown into one being strictly excluded from the square, filled the surrounding streets and houses, and gazed silently on the simple ceremonial before them. It was sunset, or nearly so – a calm, bright spring evening. There was no cheering, no disturbance, no display of banners, no rude sound of drum. The old trees were leafless; and no one’s free vision was disappointed. The funeral escort proper, consisting of the clergy, comprising representatives of nearly all denominations, the committee of Congress, and the city authorities – in all, not exceeding a hundred, with the body and pall bearers, alone were admitted.

They walked slowly up the middle path from the south gate, no sound being heard at the point from which I saw it, but the distant and gentle music of one military band near the Hall, and the deep tones of our ancient bell that rang when Independence was proclaimed. The military escort, the company of Washington Greys, whose duty it was to guard the body during the night, presented arms as the coffin went by; and as the procession approached the Hall, the clergy, and all others uncovered themselves, and, if awed by the genius of the place, approached reverently and solemnly. This simple and natural act of respect, or rather reverence, was most touching. It was a thing never to be forgotten. This part of the ceremonial was what I should like a foreigner to see. It was genuine and simple.

“And throughout, remember, illusion had nothing to do with it. These were simple, actual realities, that thus stirred the heart. It was no empty memorial coffin; but here were the actual honored remains of one who was part of our history – the present, the recent, and remote past. And who could avoid thinking, if any spark of consciousness remained in the old man’s heart, it might have brightened as he was borne along by the best men of Philadelphia, on this classic path, in the shadow of this building, and to the sound of this bell. The last of the days of Washington was going by, and it was traversing the very spot, where, seventy years ago, John Adams had first suggested Washington as Commander-in-chief of the army of the Revolution. It reposed last night in Independence Hall.”

Mr. Reed accompanied him, as his family supposed, and as he probably intended, only as part of an escort, for a short distance. From New York he wrote to his wife that, yielding to the General’s solicitations, he had become a soldier, and joined the staff as Aid, and Military Secretary. The young mother – for she was then watching by the cradle of two infant children – neither repined nor murmured. She knew that it was no restless freak, or transient appetite for excitement, that took away her husband; for no one was more conscious than she how dear his cheerful home was, and what sweet companionship there was in the mother and her babes. It was not difficult to be satisfied that a high sense of duty was his controlling influence, and that hers it was “to love and be silent.”

At Philadelphia she remained during Mr. Reed’s first tour of duty at Cambridge; and afterwards, in 1776, when being appointed Adjutant-General, he rejoined the army at New York. In the summer of that year, she took her little family to Burlington; and in the winter, on the approach of the British invading forces, took deeper refuge at a little farmhouse near Evesham, and at no great distance from the edge of the Pines.

We, contented citizens of a peaceful land, can form little conception of the horrors and desolation of those ancient times of trial. The terrors of invasion are things which nowadays imagination can scarcely compass. But then, it was rugged reality. The unbridled passions of a mercenary soldiery, compounded not only of the brutal element that forms the vigor of every army, but of the ferocity of Hessians, hired and paid for violence and rapine, were let loose on the land. The German troops, as if to inspire especial terror, were sent in advance; and occupied, in December, 1776, a chain of posts extending from Trenton to Mount Holly, Rhal commanding at the first, and Donop at the other. General Howe, and his main army, were rapidly advancing by the great route to the Delaware. On the other hand, the river was filled with American gondolas, whose crews, landing from time to time on the Jersey shore, by their lawlessness, and threats of retaliation, kept the pacific inhabitants in continual alarm. The American army, if it deserved the name, was literally scattered along the right bank of the Delaware; Mr. Reed being with a small detachment of Philadelphia volunteers, under Cadwalader, at Bristol.

Family tradition has described the anxious hours passed by the sorrowing group at Evesham. It consisted of Mrs. Reed, who had recently been confined, and was in feeble health, her three children, an aged mother, and a female friend, also a soldier’s wife; the only male attendant being a boy of fourteen or fifteen years of age. If the enemy were to make a sudden advance, they would be entirely cut off from the ordinary avenues of escape; and precautions were taken to avoid this risk. The wagon was ready, to be driven by the boy we have spoken of, and the plan was matured, if they failed to get over the river at Dunk’s or Cooper’s Ferry, to cross lower down, near Salem, and push on to the westward settlements. The wives and children of American patriot-soldiers thought themselves safer on the perilous edge of an Indian wilderness, than in the neighborhood of the soldiers who, commanded by noblemen – by “men of honor and cavaliers,” for such, according to all heraldry, were the Howes and Cornwallises, the Percies and Rawdons of that day – were sent by a gracious monarch to lay waste this land. The English campaigning of our Revolution – and no part of it more so than this – is the darkest among the dark stains that disfigure the history of the eighteenth century; and if ever there be a ground for hereditary animosity, we have it in the fresh record of the outrages which the military arm of Great Britain committed on this soil. The transplanted sentimentalism which nowadays calls George III a wise and great monarch, is absolute treason to America. There was in the one Colony of New Jersey, and in a single year, blood enough shed, and misery enough produced, to outweigh all the spurious merits which his admirers can pretend to claim. And let such forever be the judgment of American history.

It is worth a moment’s meditation to pause and think of the sharp contrasts in our heroine’s life. The short interval of less than six years had changed her not merely to womanhood, but to womanhood with extraordinary trials. Her youth was passed in scenes of peaceful prosperity, with no greater anxiety than for a distant lover, and with all the comforts which independence and social position could supply. She had crossed the ocean a bride, content to follow the fortunes of her young husband, though she little dreamed what they were to be. She had become a mother; and, while watching by the cradle of her infants, had seen her household broken up by war in its worst form – the internecine conflict of brothers in arms against each other – her husband called away to scenes of bloody peril, and forced, herself, to seek uncertain refuge in a wilderness. She too, let it be remembered, was a native born Englishwoman, with all the loyal sentiments that beat by instinct in an Englishwoman’s heart – reverence for the throne, the monarch, and for all the complex institutions which hedge that mysterious oracular thing called the British Constitution. “God save the king,” was neither then, nor is it now, a formal prayer on the lips of a British maiden. Coming to America, all this was changed. Loyalty was a badge of crime. The king’s friends were her husband’s and her new country’s worst enemies. That which, in the parks of London, or at the Horse Guards, she had admired as the holiday pageantry of war, had become the fearful apparatus of savage hostility. She, an Englishwoman, was a fugitive from the brutality of English soldiers. Her destiny, her fortunes, and more than all, her thoughts, and hopes, and wishes, were changed; and happy was it for her husband that they were changed completely and thoroughly, and that her faith to household loyalty was exclusive.

Hers it was, renouncing all other allegiance –

“In war or peace, in sickness, or in health,

In trouble and in danger, and distress,

Through time and through eternity, to love.”

“I have received,” she writes, in June, 1777, to her husband, “both my friend’s letters. They have contributed to raise my spirits, which, though low enough, are better than when you parted with me. The reflection how much I pain you by my want of resolution and the double distress I occasion you, when I ought to make your duty as light as possible, would tend to depress my spirits, did I not consider that the best and only amends is, to endeavor to resume my cheerfulness, and regain my usual spirits. I wish you to know, my dearest friend, that I have done this as much as possible, and beg you to free your mind from every care on this head.”

But to return to the narrative – interrupted, naturally, by thoughts like these. The reverses which the British army met at Trenton and Princeton, with the details of which every one is presumed to be familiar, saved that part of New Jersey where Mrs. Reed and her family resided from further danger; and on the retreat of the enemy, and the consequent relief of Philadelphia from further alarm, she returned to her home. She returned there with pride as well as contentment; for her husband, inexperienced soldier as he was, had earned military fame of no slight eminence. He had been in nearly every action, and always distinguished. Washington had, on all occasions, and at last in an especial manner, peculiarly honored him. The patriots of Philadelphia hailed him back among them; and the wife’s smile of welcome was not less bright because she looked with pride upon her husband.

Brief, however, was the new period of repose. The English generals, deeply mortified at their discomfiture in New Jersey, resolved on a new and more elaborate attempt on Philadelphia; and in July, 1777, set sail with the most complete equipment they had yet been able to prepare, for the capes of the Chesapeake. On the landing of the British army at the head of Elk, and during the military movements that followed, Mrs. Reed was at Norristown, and there remained, her husband having again joined the army, till after the battle of Brandywine, when she and her children were removed first to Burlington, and thence to Flemington. Mr. Reed’s hurried letters show the imminent danger that even women and children ran in those days of confusion. “It is quite uncertain,” he writes on 14th September, 1777, “which way the progress of the British army may point. Upon their usual plan of movement, they will cross, or endeavor to cross, the Schuylkill, somewhere near my house; in which case I shall be very dangerously situated. If you could possibly spare Cato, with your light wagon, to be with me to assist in getting off if there should be necessity, I shall be very glad. I have but few things beside the women and children; but yet, upon a push, one wagon and two horses would be too little.”

Mrs. Reed’s letters show her agonized condition, alarmed as she was, at the continual and peculiar risk her husband was running. A little later (in February, 1778), Mrs. Reed says, in writing to a dear female friend: “This season which used to be so long and tedious, has, to me, been swift, and no sooner come than nearly gone. Not from the pleasures it has brought, but the fears of what is to come; and, indeed, on many accounts, winter has become the only season of peace and safety. Returning spring will, I fear, bring a return of bloodshed and destruction to our country. That it must do so to this part of it, seems unavoidable; and how much of the distress we may feel before we are able to move from it, I am unable to say. I sometimes fear a great deal. It has already become too dangerous for Mr. Reed to be at home more than one day at a time, and that seldom and uncertain. Indeed, I am easiest when he is from home, as his being here brings danger with it. There are so many disaffected to the cause of their country, that they lie in wait for those who are active; but I trust that the same kind presiding Power which has preserved him from the hands of his enemies, will still do it.”

Nor were her fears unreasonable. The neighborhood of Philadelphia, after it fell into the hands of the enemy, was infested by gangs of armed loyalists, who threatened the safety of every patriot whom they encountered. Tempted by the hard money which the British promised them, they dared any danger, and were willing to commit any enormity. It was these very ruffians, and their wily abettors, for whom afterwards so much false sympathy was invoked. Mr. Reed and his family, though much exposed, happily escaped these dangers.

During the military operations of the Autumn of 1777, Mr. Reed was again attached as a volunteer to Washington’s staff, and during the winter that followed – the worst that America’s soldiers saw – he was at, or in the immediate neighborhood, of Valley Forge, as one of a committee of Congress, of which body he had some time before been chosen a member. Mrs. Reed, with her mother and her little family, took refuge at Flemington, in the upper part of New Jersey. She remained there till after the evacuation of Philadelphia and the battle of Monmouth, in June, 1778.

While thus separated from her husband, and residing at Flemington, new domestic misfortune fell on her, in the death of one of her children by smallpox. How like an affectionate heart-stricken mother is the following passage, from a letter written at that time. Though it has no peculiar beauty of style, there is a touching genuineness which every reader – at least those who know a mother’s heart under such affliction – will appreciate.

“Surely,” says she, “my affliction has had its aggravation, and I cannot help reflecting on my neglect of my dear lost child. For thoughtful and attentive to my own situation, I did not take the necessary precaution to prevent that fatal disorder when it was in my power. Surely I ought to take blame to myself. I would not do it to aggravate my sorrow, but to learn a lesson of humility, and more caution and prudence in future. Would to God I could learn every lesson intended by the stroke. I think sometimes of my loss with composure, acknowledging the wisdom, right, and even the kindness of the dispensation. Again I feel it overcome me, and strike the very bottom of my heart, and tell me the work is not yet finished.”

Nor was it finished, though in a sense different from what she apprehended. Her children were spared, but her own short span of life was nearly run. Trial and perplexity and separation from home and husband were doing their work. Mrs. Reed returned to Philadelphia, the seat of actual warfare being forever removed, to apparent comfort and high social position. In the fall of 1778, Mr. Reed was elected President, or in the language of our day, Governor of Pennsylvania. His administration, its difficulties and ultimate success belong to the history of the country, and have been elsewhere illustrated. It was from first to last a period of intense political excitement, and Mr. Reed was the high target at which the sharp and venomous shafts of party virulence were chiefly shot.

The suppressed poison of loyalism mingled with the ferocity of ordinary political animosity, and the scene was in every respect discreditable to all concerned. Slander of every sort was freely propagated. Personal violence was threatened. Gentlemen went armed in the streets of Philadelphia. Folly on one hand and fanaticism on the other, put in jeopardy the lives of many distinguished citizens, in October, 1779, and Mr. Reed by his energy and discretion saved them. There is extant a letter from his wife, written to a friend, on the day of what is well known in Philadelphia, as the Fort Wilson riot, dated at Germantown, which shows her fears for her husband’s safety were not less reasonable, when he was exposed to the fury of an excited populace, than to the legitimate hostility of an enemy on the field of battle:

“Dear Sir: l would not take a moment of your time to tell you the distress and anxiety I feel, but only to beg you to let me know in what state things are, and what is likely to be the consequence. I write not to Mr. Reed because I know he is not in a situation to attend to me. I conjure you by the friendship you have for Mr. Reed, don’t leave him. – E. R.”

And throughout this scene of varied perplexity, when the heart of the statesman was oppressed by trouble without – disappointment, ingratitude – all that makes a politician’s life so wretched, he was sure to find his home happy, his wife smiling and contented, with no visible sorrow to impair her welcome, and no murmur to break the melody of domestic joy. It sustained him to the end. This was humble, homely heroism, but it did its good work in cheering and sustaining a spirit that might otherwise have broken. Let those disparage it who have never had the solace which such companionship affords, or who never have known the bitter sorrow of its loss.

In May, 1780, Mrs. Reed’s youngest son was born. It was of him, that Washington, a month later wrote, “I warmly thank you for calling the young Christian by my name,” and it was he who more than thirty years afterwards, died in the service of his country, not less gloriously because his was not a death of triumph. George Washington Reed, a Commander in the U. S. Navy, died a prisoner of war in Jamaica, in 1813. He refused a parole, because unwilling to leave his crew in a pestilential climate; and himself perished.

It was in the fall of 1780 that the ladies of Philadelphia united in their remarkable and generous contribution for the relief of the suffering soldiers, by supplying them with clothing. Mrs. Reed was placed, by their united suffrage, at the head of this association. The French Secretary of Legation, M. de Marbois, in a letter that has been published, tells her she is called to the office as “the best patriot, the most zealous and active, and the most attached to the interests of her country.” Notwithstanding the feeble state of her health, Mrs. Reed entered upon her duties with great animation. The work was congenial to her feelings. It was charity in its genuine form and from its purest source – the voluntary outpouring from the heart. It was not stimulated by the excitements of our day – neither fancy fairs, nor bazaars; but the American women met, and seeing the necessity that asked interposition, relieved it. They solicited money and other contributions directly, and for a precise and avowed object. They labored with their needles and sacrificed their trinkets and jewelry. The result was very remarkable. The aggregate amount of contributions in the City and County of Philadelphia, was not less than 7,500 dollars, specie; much of it, too, paid in hard money, at a time of the greatest appreciation. “All ranks of society,” says President Reed’s biographer, ” seem to have joined in the liberal effort, from Phillis, the colored woman, with her humble seven shillings and six pence, to the Marchioness de La Fayette, who contributed one hundred guineas in specie, and the Countess de Luzerne, who gave six thousand dollars in continental paper.” La Fayette’s gentlemanly letter to Mrs. Reed is worth preserving.

HEAD QUARTERS, June the 25th, 1780.

MADAM,

In admiring the new resolution, in which the fair ones of Philadelphia have taken the lead, I am induced to feel for those American ladies, who being out of the Continent cannot participate in this patriotic measure. I know of one who, heartily wishing for a personal acquaintance with the ladies of America, would feel particularly happy to be admitted among them on the present occasion. Without presuming to break in upon the rules of your respected association, may I most humbly present myself as her ambassador to the confederate ladies, and solicit in her name that Mrs. President be pleased to accept of her offering.

With the highest respect, I have the honor to be,

Madam, your most obedient servant,

LA FAYETTE.

Mrs. Reed’s correspondence with the Commander-in-chief on the subject of the mode of administering relief to the poor soldiers, has been already published, and is very creditable to both parties. Her letters are marked by business-like intelligence and sound feminine common sense, on subjects of which as a secluded woman she could have personally no previous knowledge, and Washington, as has been truly observed, “writes as judiciously on the humble topic of soldier’s shirts, as on the plan of a campaign or the subsistence of an army.”

All this time, it must be borne in mind, it was a feeble, delicate woman, who was thus writing and laboring, her husband again away from her with the army, and her family cares and anxieties daily multiplying. She writes from her country residence on the banks of Schuylkill, as late as the 22d of August, 1780: “I am most anxious to get to town, because here I can do little for the soldiers.” But the body and the heroic spirit were alike overtasked, and in the early part of the next month, alarming disease developed itself, and soon ran its fatal course. On the 18th of September, 1780 – her aged mother, her husband and little children, the oldest ten years old, mourning around her – she breathed her last at the early age of thirty-four. There was deep and honest sorrow in Philadelphia, when the news was circulated that Mrs. Reed was dead. It stilled for a moment the violence of party spirit. All classes united in a hearty tribute to her memory.

Nor is it inappropriate in closing this brief memoir, to notice a coincidence in local history; a contrast in the career and fate of two women of these times, which is strongly picturesque.

It was on the 25th of September, 1780, seven days after Mrs. Reed was carried to her honored grave, and followed thither by crowds of her own and her husband’s friends, that the wife of Benedict Arnold, a native born Philadelphia woman, was stunned by the news of her husband’s detected treachery and dishonor. Let those who doubt the paramount duty of every man and every woman, too, to their country, and the sure destiny of all who are false to it, meditate on this contrast. Mrs. Arnold had been a leader of what is called fashion, in her native city, belonging to the spurious aristocracy of a provincial town – a woman of beauty and accomplishment and rank. Her connections were all thorough and sincere loyalists, and Arnold had won his way into a circle generally exclusive and intolerant by his known disaffection, and especially his insolent opposition to the local authorities, and to Mr. Reed as the chief executive magistrate. The aristocratic beauty smiled kindly on a lover who felt the same antipathies she had been taught to cherish. While Mrs. Reed and her friends were toiling to relieve the wants of the suffering soldiers – in June, July and August, 1780, Mrs. Arnold was communing with her husband, not in plans of treason, but in all his hatreds and discontents. He probably did not trust her with the whole of the perilous stuff that was fermenting in his heart; for it was neither necessary nor safe to do so. But he knew her nature and habits of thought well enough to be sure that if success crowned his plan of treason, and if honors and rewards were earned, his wife would not frown, or reject them because they had been won by treachery. And he played his game out, boldly, resolutely, confidently. The patriot woman of Philadelphia sank into her grave, honored and lamented by those among whom so recently she had come a stranger. Her tomb, alongside of that of her husband, still stands on the soil of her country. The fugitive wife of an American traitor fled forever from her home and native soil, and died abroad unnoticed, and by her husband’s crime dishonored. She was lost in a traitor’s ignominy. Such was then and such ever will be, the fate of all who betray a public and a patriot trust.