Contents

Contents

Introduction

EARLY Pennsylvania was an ethnic and religious patchwork. A greater variety of races and creeds found homes within its borders than in any other colony. Clinging together and settling in groups, they dotted the early province with a curious pattern of self-sufficient communities, each attempting to preserve its own manners and ideals, each resisting, but not preventing, partial assimilation.

The flags of Holland and Sweden had flown over portions of the colony, and traders and settlers from both countries had appeared along the shores of the Delaware as early as 1632. Though the real history of Pennsylvania begins with the granting of the royal charter of 1681, the settlements previous to that date were not without significance. The little villages of Swedes, Dutch, English, and Finns, scattered along the banks of the Delaware, were quietly prosperous communities, pleasantly pastoral in character. They hugged the river, little attempt being made to open up the belt of forest skirting the shores; for these settlers were less aggressive than most. They had been content to cultivate the rich river bottoms, to fill the meadows with their red cattle, to cut ditches and dikes, and to plant orchards. and gardens. They might have given complexion to the future of the colony; but their numbers were too scanty to resist the influx following the granting of the charter. They lost their identity rapidly and became absorbed by the waves of English, Welsh, Germans, and Scotch- Irish that swept into the colony.

The granting of the charter which gave William Penn almost sovereign power over the colony was the signal for the release of a great stream of migration. Penn, although a Quaker, opened his lands not only to the members of his own sect but to “all who confess and acknowledge one Almighty and eternal God to be the creator, upholder and ruler of the world, and that hold themselves obliged to live peaceably and justly in civil society.”

The development of the colony began late, but, once under way, its growth was astonishing. In 1681 there were perhaps six thousand souls within its borders; the forest stretched unbroken from the river bank westward to beyond the Alleghanies. A century later it was one of the richest, most populous and important of the commonwealths; its principal city had grown to be the largest on the continent, another of its cities the largest inland municipality; and its pioneers were raising their cabins in the river valleys of the Great Basin.

When William Penn landed at New Castle in 1682 “amid the welcoming shouts of Dutch and Swedish settlers in woodland garb, the men in leather breeches and jerkins,” the women “in skin jackets and linsey petticoats,” he found his young colony had already taken root. There were no Indian dangers, the wellstocked farms of the Swedes and Dutch were a guarantee against famine, and the climate was temperate and healthful. To Penn the new country seemed like “the best vales of England watered by brooks; the air, sweet; the heavens, serene like the south of France; the seasons, mild and temperate; vegetable production abundant, chestnut, walnut, plums, muscatel grapes, wheat and other grains; a variety of animals, elk, deer, squirrel and turkeys weighing forty or fifty pounds, water birds and fish of divers kinds, no want of horses, and flowers lovely for color, greatness, figure and variety. The stories of our necessity [have been] either the fear of our friends, or the scarecrows of our enemies; for the greatest hardships we have suffered hath been salt meat, which by fowl in winter and fish in summer, together with some poultry, lamb, mutton, veal and plenty of venison, the best part of the year has been made very possible.”

It is evident the early Pennsylvanians suffered little of the distress falling to the lot of most colony founders. They labored to such purpose that by the end of 1683 the newly laid out site of Philadelphia contained three hundred and fifty-seven dwellings, many of them of framed wood, some of red brick. Settlers continued to stream in, hungry for land. Almost overnight Philadelphia became the principal port of entry in the colonies. The English Quakers continued to come in numbers, and new races and faiths were carried in on the rising flood of migration – German Protestants of a dozen sects, Scotch-Irish Presbyterians, Moravians, Dutch Baptists, Welsh Quakers and Baptists, and some Irish Catholics.

There were almost no men of wealth in the ranks of the new-comers. They were recruited largely from the yeomen and peasant classes; men who had their way to make in the world; seekers after homesteads of a workable size. Their numbers, earnestness, and energy helped to establish Pennsylvania among the leaders of the colonies; but the tendency of each race and faith to settle apart prevented the colony from becoming a unit in thought and action.

Philadelphia attracted numbers from each group; yet it was essentially a Quaker town, with a strong representation of English of the Church of England persuasion. The counties adjacent to the city were also held by the Quakers. The next band of counties, Lancaster, Berks, Lehigh, and parts of Montgomery and Bucks were occupied by the Germans. Beyond, along the Susquehanna and in the Cumberland Valley, were the Scotch-Irish settlements. A fourth group were the Welsh, who settled themselves on the “Welsh Barony, ” about the towns of Merion, Haverford, and Radnor, just west of Philadelphia. This racial grouping was a serious obstacle to unity; yet, even in the days of its beginnings, the colony achieved a marked individuality, developing an atmosphere singularly simple and tolerant.

Religion was in the air during the early years. Both Quakers and German Pietists were people who made no separation between their religious and secular lives; who carried the admonitions of the meeting-house into the encounters of everyday life. The sobriety and earnestness characterizing this early life resisted for many years the pressure of continued immigration and economic expansion. Pennsylvania was probably subject to a greater variety of influences and contacts than any of the other provinces; but the origins of the colony were Quaker, and Quaker ideals and manners were, for a long time, the most potent factors in its growth.

When the Quakers first appeared upon the Pennsylvania scene their faith was still a new one, and many of its forms were far from being crystallized. In the matter of dress – and it bulked large in the precepts of their church – they had been merely admonished to clothe themselves plainly and soberly, and to avoid all appearance of vanity or luxury. In no sense did they bring to the new country a uniform or stereotyped form of dress. Their clothes were those of the English world of Charles II. Their garments were cut like those following the general vogue of the day. Their own contribution was the elimination of the applied decoration – the braid, ornate buttons, ribbons, plumes, and laces; in the avoidance of conspicuous materials and colors, and in the sober air with which they wore their quiet dress. The so-called Quaker costume of the time was not a new and different type of dress, merely a simplified and unadorned version of the current mode. Once plainness and sobriety had been achieved, the tendency was to retain the form in spite of the influence of passing fashions. Thus, in a few decades, the Quaker was well behind the mode, and by marking time had, in the matter of dress, passed from a radical to a conservative position. It was only then, when the quickly succeeding fashions had left them in the dress of a past generation, that Quaker costume became at all standardized. It never remained fixed in form. Reluctantly and sparingly it borrowed from the changing dress about it, and followed at the distance of a generation or two the curious fashions of the outside world.

As the colony grew and amassed material benefits, the old familiar cleavage between town and country life appeared. The cleavage expressed itself as eloquently in dress as in other ways, and the costume of many of the Quaker town-dwellers felt the impact of wealth and outside influences. The country folk, secure from worldly contacts, kept their gray and brown simplicity almost untouched; but those of the city who had felt the quickening touch of prosperity usually found some compromise necessary.

Philadelphia, through the expanding years of the eighteenth century, grew into the first city of the land. The ships of the world dropped anchor in the Delaware; her warehouses were piled high with the plunder of the markets of East and West; the back-country added its supplies of foodstuffs, fur, iron, lumber, glass, and paper. The luxuries of the early days became the necessities of the late century. Carpets, chintz hangings, India prints, wall-papers, and complete services of silver were commonplace. All the new and strange products of the world’s workshops found their way to the counters of the new city, and Philadelphia, young, lusty, and greedy for fine things, absorbed them all, filling her homes and institutions with them. The eighteenth century had effaced the last lingering touch of the medieval in art. The dignity of the Georgian had replaced the broader, sturdier architecture of the previous century; the grace and consummate craftsmanship of Chippendale and Adam had succeeded the heavier lines of the Jacobean and William and Mary styles. It was an age in which an art of great refinement and sophistication reached fruition, and with it grew up a society of equal refinement and sophistication. In all the continent of North America there was no center more receptive to this art and society than Philadelphia. By the time of the Revolution the luxury and extravagance of the city had reached its peak. Its culmination was the great “Mischianza,” that Georgian version of medieval pageantry and tournament.

Exposed to the color and attraction of this setting, and of necessity actively engaged in affairs compelling them to rub elbows with the world, it was inevitable many of the Quakers should find the color and variety of new fashions irresistible. In the gay Philadelphia society of the eighteenth century, which adopted the latest London vogue as quickly as fast sailing ships could bring it, it would have been impossible to pick out the wealthier and more worldly Quakers through any difference in their dress. There were others, not unaffected by the fashion of the day, who were unsympathetic with its excesses, and who worked out a compromise between the Quaker and the worldly ideal. Yet the great body of Quakers clung to quiet grays and browns, cutting their clothes in styles out of vogue for a generation or more.

In a general way, the same principles and influences to which the costume of the Quakers was subjected can be applied to that of the various sects of German, Pietists. They, too, were “plain people,” frowning upon anything that smacked of ostentation. Yet, although they all worked toward an ideal of simplicity, each sect had its own restrictions and prohibitions, and each differed from the others in minor ways. Mennonites, Schwenkfelders, Amish, Dunkards, Seventh-Day Baptists, United Brethren, and others all worked out the problems of plain dressing in their own way. If the general result was the same, the minor complications were many, demanding a volume of their own. Once having found a dress expressing their ideal of plainness, they held to it tenaciously, suffering few changes to be made. This was all the more possible, since, living in a district of their own, they were isolated from the rest of the colony. They have in part preserved their language and habits down to the present day.

Other racial groups brought certain distinctive articles of dress that gradually disappeared under the compulsion of a new life, as in the case of the high, conical-shaped hats of the Welsh women, and the wooden shoes of some of the German peasant redemptioners. In the main, where individual tastes were not guided by religious convictions, the tendency was to drop the peculiarities of the homeland and to put on the habits of the new. In the Pennsylvania of the eighteenth century all the color and glitter were concentrated in Philadelphia. Around it lapped bands of Quaker gray and Pietist drab; beyond these the homespun and buckskin of the border country.

1. COSTUME OF THE QUAKERS: MEN

The male costume of the Quakers who came to America shortly after the signing of the charter was in the late fashion of Charles II’s time. A comparison between the costume of a man of fashion with the dress of a Quaker gentleman in America during these years will point out the differences that existed. Among the gaily dressed men of the world, the Quaker costume was markedly conspicuous, not because it was different in cut and style, but on account of the lack of the popular extravagances which had become such an important part of the fashionable dress of the time. The Quakers had not, as is usually supposed, adopted a distinctive type of dress at this period, but from the very beginning a note of neatness, plainness, and simplicity pervaded their attire. Quaker simplicity and plainness, however, did not mean cheapness, as the material possessions of the Quakers were of the best. Their houses were furnished with the best walnut and mahogany furniture, though restrained in carving and decoration. The most costly silver and china, the finest of imported rugs and carpets went into their homes; and the best of materials into their dress.

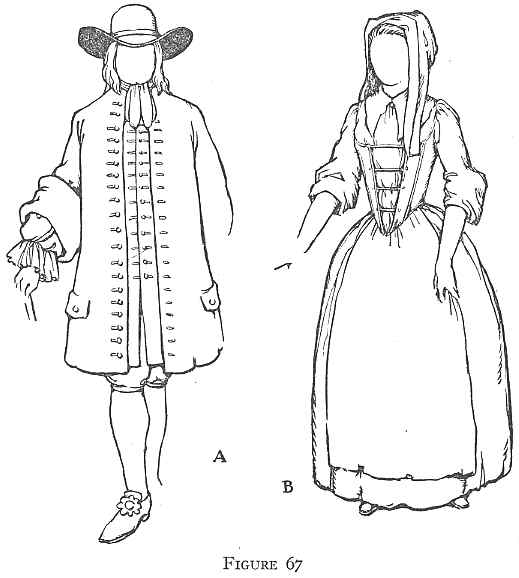

COATS AND WAISTCOATS. – If Figure 43 B is compared with Figure 67 A, it will be noticed that the cut of the two coats is identical, in both cases reaching to the knees and extending several inches beyond the long waistcoats. The sleeves have the great turned-back cuffs from the middle of the forearm to beyond the elbow. It will be noticed, however, there is a staidness and plainness in the Quaker garment, a lack of figured materials, noticeable in the great turned-back cuffs and waistcoat of the fashionably dressed man. Further, there is a noticeable lack of embroidery and braid around the edges of the coat and waistcoat in the Quaker garment.

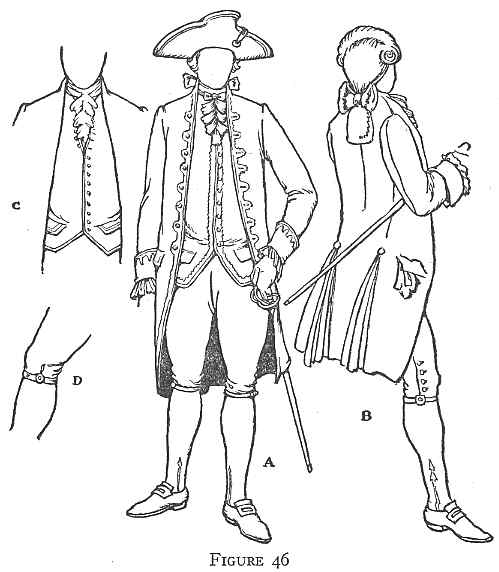

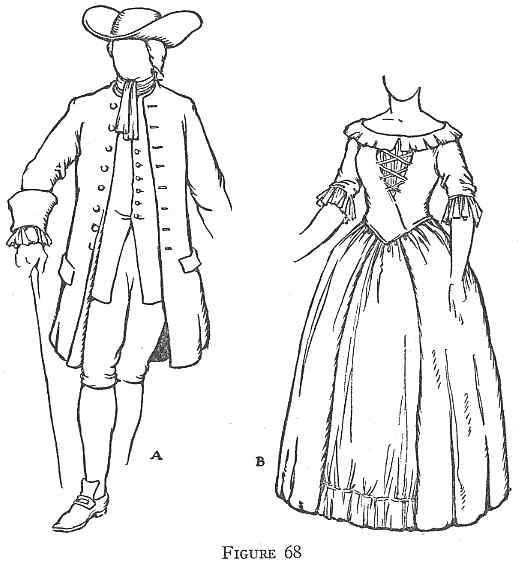

By comparing Figure 46 A with Figure 68 A, both men being dressed in the costume just previous to and during the Revolution, it will be found the Quaker had not as yet accepted the newer coat and waistcoat, but was still garbed in the costume of about 1750. (See Fig. 45 A.) The Quaker’s coat and waistcoat were still unadorned and noticeably free of embroidery, braids, and edging.

BREECHES. – Breeches are about the same, though the Quakers never seem to have worn the full exaggerated breeches such as were worn during these early years by the more fashionably dressed men. Later, however, they were about the same.

LINEN.-While the linen worn by the Quakers was splendid in quality and often edged with lace, it never became as rich and extravagant as that worn by the “world’s people.” In Figure 67 A can be seen the neckcloth, that came in about 1660. It is passed around the neck and tied under the chin with short spreading ends, while in Figure 43 B the ends of the neck-cloth are brought together and fastened at the throat with a ribbon bow.

In Figure 68 A the Quaker gentleman is wearing the cravat fashionable in the eighties, when the tie was lengthened and fell freely down the front in two long ends, carried over the neck-band. In 46 A we see the more fashionable frill of lace, known as the jabot, appearing under the neck-band. The solitaire is worn in combination with the bag-wig and the jabot.

FOOT-GEAR. – In comparing the shoes worn in 67 A with 43 B, the Quaker still retains the shoe roses, though as a general fashion they are no longer met with. The newer fashion of these years is seen in the highheeled shoes, with the tongue rising high over the instep, in place of the shoe rose, the shoe would be fastened by a buckle. Later, when the tongue was much reduced in size (46 A) the Quaker still retained the older fashion (68 A).

HAIR. – While the gentlemen of the world wore the long curled and powdered or black periwig, the Quaker was apt to wear his own hair falling over his shoulders, but “Wigs were as generally worn by genteel Friends as by other people.” The wig of the Quaker seems, however, to have been less voluminous and dandified.

HATS. – The Quaker hat in 1680 was practically the same as that worn by other men, only instead of cocking the brim at various angles he preferred to wear his hat with a natural wide brim uncocked (Fig. 67 A). Among the Quakers the hat was kept on the head most of the time, whether indoors or out. He refused to lift it in the form of a salute; this to the Quaker mind was an affectation. Later on, the cocked hat as well as the broad-brim hat was worn. Mrs. Gummere states, “The broad brim and the cock are the two forms of the Quaker hat.” In 68 A is seen the Quaker hat with the brim rolled up at the sides in quite an angle, but it never rivaled the exaggerated cock of the Kevenhuller worn by the gentlemen in Figure 46 A.

II. COSTUME OF THE QUAKERS: WOMEN

BODICE AND SKIRT. – The gown of the Quaker woman of about 1682 is seen in Figure 67 B, and represents the general style of Quaker dress for many years to come. The opening at the neck is filled in with a fine linen or lawn kerchief, carried down the front, the opening of the bodice being laced across. The same material seen in the kerchief appears from under the elbow sleeves. The full skirt is gathered into full pleats to the bodice. Over the silk gown is worn the apron. A comparison of this costume with the costume seen in Figure 55 A shows in the latter the low cut of the bodice, the full-looped skirt held in place with ribbon ties over a satin petticoat edged along the lower border with two flounces of lace. The bodice, open over the stomacher, has a row of graduated ribbons, known as the échelles, down the front. Instead of the plain undersleeves of the Quaker dress, we find sleeves of fine lawn or lace, puffed at the elbow and finished with lace ruffles.

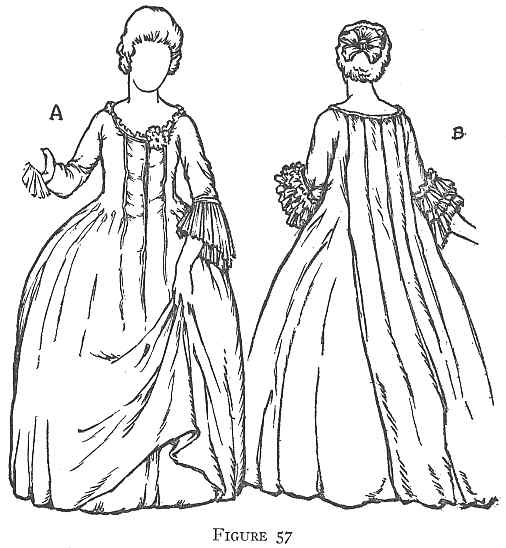

The costume of a Quaker lady on the eve of the Revolution is shown in Figure 68 B, though it is in the fashion of about 1735-40. The modish costume of this time (1775) was the robe à la française (Fig. 57) or the polonaise (Fig. 59). The bodice (Fig. 68 B) is laced over a white stomacher, the sleeves of elbow length. Edging the slight décolletage appears the ruffle of a lawn undergarment turned over the neck like a falling band. The split skirt was worn over hoops, exposing the petticoat, but not nearly so distended as that of the woman of fashion.