Contents

Contents

Chapters

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Invasion of Canada is Planned

- Chapter 2: Benedict Arnold

- Chapter 3: The Expedition Sets Forth

- Chapter 4: The Ascent of the Kennebec

- Chapter 5: The March into the Wilderness

- Chapter 6: Flood, Famine, Desertion

- Chapter 7: Across the “Terrible Carry"

- Chapter 8: Arnold Saves the Remnant of His Army

- Chapter 9: Descending the Chaudière

- Chapter 10: Before Quebec

- Chapter 11: Montgomery Joins Arnold

- Chapter 12: The Investment

- Chapter 13: The Assault Is Planned

- Chapter 14: The Assault on Quebec

- Chapter 15: The Death of Montgomery

- Chapter 16: The Americans Stand Their Ground

- Chapter 17: Prisoners of War

- Chapter 18: A Hopeless Siege

- Chapter 19: The Campaign Fails

- Appendix

The 16th day of September being Sunday, the troops at Newburyport attended divine worship at Rev. Jonathan Parson’s meeting-house, or listened to their chaplain, Rev. Mr. Spring. The next day a grand review was held, and on the 18th the whole detachment embarked on board ten transports: among them the Commodore, the flagship, carrying Arnold; the sloops Britannia, Conway, Abigail and Swallow; the schooners Houghton, Eagle, Hannah and Broad Bay, the latter under Captain James Clarkson, who was to act as sailing-master for the fleet.

Three small boats had been sent forward to ascertain if there were any British vessels in the offing. One of these having returned and reported the coast clear, the following morning about ten o ‘clock the transports weighed anchor and with “colors flying, drums and fifes playing, the hills all around being covered with pretty girls weeping for their departing swains,” set sail. The fleet was bound, sailing N.N.E. with pleasant weather and a fair wind, for the mouth of the Kennebec River, one hundred and fifty miles from Newburyport.

The vessels crossed the bar before Newburyport harbor and lay to, while the Swallow, which had stuck fast on a rock, was lightened of her quota of troops and gotten safely off. It was not till two in the afternoon that the signal for sailing was again given. The fleet ran along shore until midnight, when, in response to another signal, they hove to with head off shore, near Wood’s island.

The wind had increased, and the sea was so rough by night that King Neptune raised his taxes without the least difficulty where King George had failed, and the reluctant soldiers “disgorged themselves of the luxuries so plentifully laid in ere they embarked.” During the night the hardy backwoodsmen and farmers had a true taste of the sea, for the waves dashed high, it thundered and lightened, and the morning of the 20th dawned with fog and heavy rain. They made sail early in the morning and arrived at one P. M. at the mouth of the Kennebec. Here they anchored for six hours at Ell’s Eddy, and then proceeded as far as Georgetown, where they lay to all night.

While the fleet of transports were at anchor at Parker’s Flats, the Georgetown minister, Rev. Ezekiel Emerson, and one of his deacons, Jordan Parker, came aboard the Commodore to pay their respects to Arnold and the officers. Impressed with the importance and hazardous nature of the enterprise, the devout parson thought it incumbent upon him to offer a prayer in length commensurate to all the circumstances. His invocation was continued (so tradition asserts) for an hour and three-quarters, with what effect on the officers and crew is not recorded.

As the vessels in advance entered the Kennebec, a number of men under arms hailed them from the shore, and upon being answered that the vessels carried Continental troops and were in need of a pilot, immediately sent one on board. The rest of the fleet, separated during the night in the fog and the storm, were anxiously awaited. However, all came up during the day, except the Conway and the Abigail. Wind and tide now favoring, they proceeded up the Kennebec past the island hamlet called “Rousack,” or Arrowsic, across the broad expanse of Merry-Meeting Bay, where the waters of the Androscoggin and five other smaller streams join the Kennebec, and finally past Swan island and the ruins of Fort Richmond, some twenty-five miles above the river’s mouth.

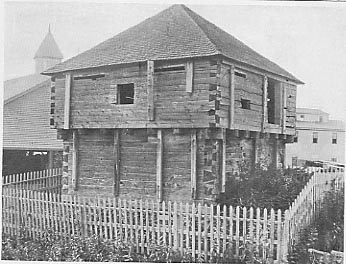

A little above this island they came to anchor opposite Pownalborough, where there were a blockhouse, a court-house and a jail, besides a rambling settlement of perhaps twoscore houses. Here they were joined by the missing sloops, which had by mistake run past the mouth of the Kennebec the day before.

Some of the ships were delayed by running upon shoals and upon Swan island, owing to faulty piloting, and during the 22d and 23d the others awaited their arrival at Pownalborough, while details were counted off to take charge of the bateaux now nearly completed at Colburn’s shipyard, a short distance above, at Agry’s Point. Within two weeks two hundred bateaux had been built and eleven hundred men levied, supplied with provisions and transported to this place, over two hundred, miles from Cambridge.

This was rapid work for those days of slender resources and slow transit.

Next day, some still sailing, some advancing in bateaux, and others marching by land, the troops reached Fort Western, six miles further up the river. This outpost consisted of two blockhouses and a large house or barrack one hundred feet long, enclosed with pickets. The headquarters were at Esquire Howard’s, “an exceedingly hospitable, opulent, polite family,” while the army built itself a board camp, as tents were few and wood plenty. For three days the little army lay at Fort Western, getting men, provisions and bateaux up from Gardinerstown and Agry’s Point, and in making final preparations for their march – at this, the last place where supplies might be obtained in the least adequate to their needs.

The halt was enlivened by festivities of a generous sort, for the citizens of the vicinity were for the most part ardent Whigs, and rejoiced in the opportunity of honoring a band of patriots embarked in so glorious an undertaking. There is mention of one feast in particular – a monstrous barbecue of which three bears, roasted whole in true frontier style, were the most conspicuous victims. Squire Howard and his neighbors contributed corn, potatoes, and melons from their gardens, quintals of smoked salmon from their storehouses, and great golden pumpkin pies from their kitchens. As if this were not sufficient, venison was plenty, and beef, pork, and bread were added from the commissary’s supplies. Messengers were sent to the local notables – William Gardiner, at Cobosseecontee; Major Colburn and Squire Oakman, at Gardinerstown; Judge Bowman, Colonel Cushing, Captain Goodwin, and Squire Bridge, of Pownalborough. Social opportunities were not over-frequent on the frontier, and all the guests invited made haste to accept, and came accompanied by their wives.

To the sound of drum and fife the soldiers were marched up to the loaded tables and seated by the masters of ceremony, while the guests and officers sat by themselves at a separate table. Dr. Senter and Dr. Dearborn, as particularly familiar with anatomy, were selected to carve the bears, and amidst the most uproarious jollity the feast proceeded. At the end toasts were drunk – presumably in the never-failing rum punch of New England – and the entertainment concluded amid patriotic airs performed upon drum and fife, and the heartiest good humor of the entire company.

One of the most interesting guests at this al fresco banquet was a young half-breed girl, Jacataqua by name, who seems to have been in some sort the sachem of a settlement of Indians on Swan island. Partaking of the best traits of her mixed blood – French and Abenaki – she is described by those who knew her as possessing unusual intelligence, self-reliance and winsomeness. The, fair visitor had already conceived a romantic attachment for young Burr, who was famous all his life for his successes with women, and according to tradition, the two had gone on several hunting expeditions together, and had, in fact, killed the three bears which furnished forth the feast described above. So genuine was the Indian girl’s affection for the young officer, in spite of the brief opportunity offered for its cultivation, that she insisted on accompanying him and his comrades to Quebec. So, at least, we are told, though it is by no means impossible that Jacataqua’s wild blood, and her familiarity with the woods and streams which lay before the little army, would have made the journey not uncongenial, even if her gentler emotions had not been stirred by the fascinating Burr. She may also have found encouragement for her resolution in the fact that the wives of James Warner and Sergeant Grier, of the rifle corps, had determined to follow their husbands to Canada, and, like Madame Sans-Gène, share with them whatever hardships and perils they were forced to meet. We shall have occasion, later in our narrative, to note more than once the constancy and fortitude of these brave women.

Here, too, at Fort Western, occurred the first loss of life – a soldier, Reuben Bishop by name, being shot and killed during some obscure quarrel by a comrade named McCormick. The murderer was sent back to Cambridge, under guard, and died in prison on the very day set for his execution.

Before the expedition was ready to move again, Berry and Getchell, two scouts who had been sent forward at Washingtons orders during the previous month, to spy out the road, made their appearance and submitted their report to Arnold. They had gone fifty or sixty miles up the Dead River, had found the road in general well enough marked, the carrying places in fair condition and the water, though shoal, no more so than was inevitable at that season of the year. They also brought news which might be considered disquieting, to the effect that they had met an Indian who told them that he had been commissioned as a spy by Governor Carleton, with instructions to warh Quebec of any hostile movements on the part of the colonists from the direction of the Kennebec. He added that there were more spies, both whites and Indians, stationed near the headwaters of the Chaudière, and having his own suspicions of Getchell’s and Berry’s business in the wilderness, he had threatened to convey instant information of their presence there to Quebec if they pushed any further up the river.

Arnold, however, seems to have been little disturbed by this intelligence, for he reported to Washington that the scouts had seen “only one Indian (Nattarius), a native of Norridgewock, a noted villain, and very little credit, I am told, is to be given to his information.” Far from regarding the presence of Indian spies along his proposed road as any excuse for hesitation or delay, he hurried forward two well-equipped scouting parties. One under Lieutenant Church, consisting of seven men, a surveyor and guide, was to take the exact course and distances of the Dead River; the other party, under Lieutenant Archibald Steele, of Smith’s company, was to ascertain and mark the paths used by Indians at the numerous carrying places in the wilderness, and also to ascertain the course of the River Chaudière, which, as we have seen, runs from the Height of Land toward Quebec.

These scouts, traveling rapidly in one small and one large birch-bark canoe and leaving Fort Western before the main body, were expected to perform their duty with great celerity, and to report to Arnold at the Twelve Mile carrying place on the Kennebec, about thirty miles above Norridgewock.

September 25, Captain Morgan, with Smith’s and Hendricks’s companies of “Riflers” constituting the first division, embarked in bateaux, the river not being further navigable, except for such flat-bottomed boats, with orders to proceed with all speed to the Twelve Mile carrying place, and to follow the footsteps of the exploring parties, examining the country along the route, freeing the streams of all impediments to their navigation, and removing all obstacles from the road: in short, to take such measures as would facilitate the passage of the rest of the army. The following day the second division, under Lieutenant-Colonel Greene, with Major Bigelow and Captains Thayer’s, Topham’s and Hubbard’s companies of musketeers, also took to their bateaux and followed the riflemen, and on the 27th the third division, under Major Meigs and consisting of Handchett’s, Dearborn’s, Ward’s and Goodrich’s companies, in its turn took up the march. Lieutenant-Colonel Enos, with William’s, McCobb’s, Scott’s and Colburn’s companies, brought up the rear.

The bateaux had been “hastily built in the most slight manner of green pine,” and though not very large were very heavy. When loaded with provisions, ammunition and camp equipage, it required the utmost exertions of four men, two at the bow and two in the stern, to haul and push them against the current in shallow water. Sixteen bateaux were set off to each company. There were fourteen companies, therefore the start was made with two hundred and twenty-four or more bateaux.

The advantages of the formation above referred to were very conspicuous on the march, as the rear divisions not only had the paths cut for them, and the rivers made passable for their boats, but encampments cleared and bough huts ready made. On the other hand, since the baggage and provisions were distributed according to the difficulties which each division must encounter, many of the first companies took only two or three barrels of flour with several casks of bread; while the companies in the last division had not less than fourteen of flour and ten of bread.

The first day’s journey was not difficult, but as the men pushed on they found the current much stronger. As they approached the Three Mile Falls, below Fort Halifax, the crews of the bateaux were obliged continually to spring out into the river and wade – often up to their chins in water, most of the time to their waists. At the foot of the falls a landing was made and the provisions and bateaux carried around the rapids. Here, and at all the other carrying places the bateaux had first to be unloaded and carried across on the shoulders of the men, with the assistance of a few oxen (the last of which, however, were slaughtered for food before the Dead River was reached). The ammunition, kegs of powder and bullets, packages of flint and steel, extra muskets and rifles – besides a musket for each soldier, axes, kegs of nails and of pitch, and carpenters’ tools for repairing the bateaux and other purposes, had to be packed across on the men’s backs, for they had no pack animals. Besides all this, casks of bread and pork, barrels of flour, bags of meal and of salt, the iron or tin kettles and cook’s kit, tents, oars, poles and general camp equipage and extra clothing (of the latter there was far too little), all must be laboriously gotten across each carrying place, repacked and reloaded in the bateaux and floated on the river against the impetuous current.

On the 28th, Arnold, who had remained at Fort Western superintending the embarkation and attendIng to the return of a few soldiers already invalided to Cambridge, entered his birch canoe with two Indians, and progressing swiftly in comparison with the loaded bateaux and the footmen of his army, soon arrived at Vassalborough, eight miles above Fort Western. Here the canoe, which leaked, was changed for a periagua, and his progress continued till within four miles of Fort Halifax, where he lodged for the night.

The first three divisions had, on the evening of September 29, passed Fort Halifax and the first carry around Ticonic Falls. That same morning the fourth division, delayed in collecting provisions and finishing bateaux, left Colburn’s shipyard. Though the leaves were already falling, the weather had been up to this time that of Indian summer, and most of the men were in the best of health and spirits. Having expected hard and rough work, they breasted the seemingly impossible with lightness and good humor. The keen, bracing air of the backwoods incited to exercise and competition; the shining river with its everchanging channels, rocky and boulder-strewn, bordered with forest and meadow, lured them into forgetfulness of the bitter northern winter, yet to be endured. Jokes and jeers were the only consolation for doubters and laggards; cheers and shouts of applause the reward of energy and perseverance. But, in spite of every effort, Meigs’ division made only seven miles on the 30th, pulling, shoving, hauling and poling most of the day, waist-deep in the water, as Arnold records, “like some sort of amphibious animals.”

Their young commander, speeding up the stream in his periagua, caught up with them about ten o’clock that morning just as they were crossing the carry around Ticonic Falls, above Fort Halifax. He lunched at eleven o’clock at one Crosier’s and then hired a team and carried his baggage overland, thus avoiding the “Five Mile ripples” above the falls, through which the bateaux crews were toiling. At five o’clock he struck the river again and proceeded up it a mile and a half, camping with the division of Major Meigs, which had consumed the remainder of the day in laboriously forcing their bateaux over the ripples.

Colonel Greene’s division, after pushing through these long stretches of ripples below and above Ticonic Falls, had found that the river widened and, like a broad blue ribbon, led them for eighteen miles through a fertile country between banks still verdant with the clothing of summer, though the low hills inland wore the solemn colors of fast-advancing autumn. The current was quick and the water very shoal in many places, but there were no other obstacles to delay them. They encamped only a few miles in advance of Meigs, at a place known as Canaan, on the west side of the stream three or four miles from the next carry, at Skowhegan Falls.

Here the river tumbled twenty-three feet over ledges of rock, divided into two cataracts by a precipitous forest-crowned island. This obstacle so retarded the current that, as the stream found escape, it thundered its rejoicings with a deafening roar and rushed on for several hundred yards through a very deep and narrow gorge with all the abandon of a mountain torrent. The carry was a most difficult one, for the heavy bateaux had to be hoisted and dragged up the steep rocky banks while the men struggled in the fierce rush of the swirling current. Meanwhile, to add to their discomforts, the weather became cold and raw, and the wet and weary soldiers were forced to build huge fires to warm themselves and dry their dripping clothing. On the night of September 30 it was so cold that the soaked uniforms could not be completely dried, and froze stiff even near the fires, the men being obliged to sleep in them in this condition.

By this time the bateaux had revealed their hurried and defective construction and had begun to leak so badly that the crews were always wet, whether wading in the water or standing in the boats, and of course the arms, ammunition and baggage which were stowed in them likewise suffered. Many were little better than common rafts, and “could we,” writes one of Arnold’s men, “have then come within reach of the villains who constructed them, they would have fully experienced the effects of our vengeance. It is no bold assertion to say that they are accessory to the death of our brethren who expired in the wilderness. May Heaven reward them according to their deeds.”

The bateaux crews were divided into two squads of four men each, the relief marching along the shore. Only four men at one time could conveniently carry the bateaux when it became necessary to do so. When the boat grounded at a carrying place its crew of four men sprang into the water beside it, and having inserted two hand-spikes under the flat bottom, one at either end, raised the boat to their shoulders and staggered with it up the bank. The relief rendered such assistance as it could in lightening the boatload, clearing the path, and helping the bearers when a more difficult obstacle than usual intervened.

When rapids were encountered it was often found impossible to pole the clumsy craft against the swift current, and the crews were obliged to take to the water, “some to the painters and others heaving at the stern.” The water was in general waist-high, and the river bottom very slippery and uneven; the crews were often carried off their feet and obliged to swim to shoaler water. Those who could not swim had sometimes very narrow escapes from being drowned. Even with their united efforts, the stream was so violent as many times to drive them back “after ten or twelve fruitless attempts in pulling and heaving with the whole boat’s crew.” Every night found the men exhausted with toil, weak and shivering from cold, hunger and fatigue. But every bright and bracing autumn morning seemed to revive anew their energy and courage.

September 30 and October 1, the second division consumed in the herculean task of passing between the Falls of Skowhegan, and in ascending “Bumbazee’s rips,” seven miles to Norridgewock, which they reached at noon. The rifle division were only one day’s journey in advance of them. Greene encamped on the west side of the river. Arnold passed the night of the 1st of October at a certain Widow Warren’s, about five miles above Skowhegan Falls. The next morning he overtook Morgan with the first division, which had just got its baggage over a steep carrying place – longer than any yet encountered – at Norridgewock Falls, and encamped close by “on a broad flat rock, the most suitable place” they could find. They had now left Fort Western, their weak base of supplies, fifty miles behind them.

October 2, pressing hard upon the second division, the third encamped on the west side of the river, opposite the island carry at Skowhegan Falls, and on the 3d reached Norridgewock, the last frontier settlement on the Kennebec, where in 1724 an expedition from New England had massacred the French Jesuit missionary, Sebastian Rale, and his whole congregation of Indian converts. The vestiges of an Indian fort and a Roman Catholic chapel, some intrenchments, and a covered way through the bank of the river, made for convenience in getting water, were still to be seen.

Several days were passed in getting boats, provisions and ammunition across this long and difficult carry (more than a mile in length), around the Falls of Norridgewock. Much valuable time was also spent in caulking and repairing the bateaux, which, mercilessly handled by the rocks and rapids, were in almost useless condition. At length the expedition was ready to move again, and on October 4 the leading companies began to push forward toward the next carrying place at Carratunk Falls, eighteen miles above. They found the country around them growing more and more hilly, the forest more continuous, and the river itself dangerously shallow. Those who followed the boats on foot could scarcely tramp fifty yards through the now almost leafless thickets without coming upon moose-tracks, and on one occasion at least the riflemen feasted on a fine young bull brought down by one of their number.

Carratunk Falls – sometimes called the Devil’s Falls -are fifteen feet in pitch, but the portage was only of fifty rods, though very rough. The river was here confined between rocks which lay in piles forty rods in length on each side; but the water was so shoal that the men became much exhausted with constantly lifting and hauling the bateaux. This point the riflemen reached October 4; the fourth division, or rear guard, was four days behind. There was no delay here, each division pushing on again as soon as the portage was crossed.

Mountains now began to appear on each side of them, high and level on the tops, and well wooded; each with a snow-cap. The highest, far distant, loomed to the westward across a dismal landscape of gloomy forest, whitened with wintry frosts, and seen through drizzling rain and river mists as chilling as the icy water in which the bateaux crews waded. Discomfort and hardship increased with each advance into the wilderness. For three or four days it had rained part, at least, of each day and night. It had been a long, dry summer, and nature was restoring the balance. From the date of their leaving Norridgewock – the last outpost of civilization – the elements seemed to combine to cool the ardor and dampen the spirits of men and officers. Lagging and straggling from sickness, laziness and wilfulness made their ominous appearance, and were checked with difficulty.

The commissariat also had its misfortunes. A supply of dried codfish which had been received after leaving Fort Western had been stored, in the confusion, loose in the bottoms of the bateaux. This was washed about in the fresh water leakage until it was all spoiled. Many barrels of dry bread too, and some of peas, having been packed in defective casks, absorbed water until they burst, and their contents had to be condemned. The rations of the soldiers were thus already reduced to pork and flour. A few barrels of salt beef remained, but it proved unwholesome as well as unpalatable.

Nevertheless, most of the men showed undiminished spirit and pressed forward bravely, some forcing the boats up the swift but shallow channels of the river, others marching along its rough and thickly overgrown banks. By the 8th the riflemen had reached the Twelve Mile carrying place, where they were to leave the Kennebec for its tributary the Dead River, and encamped there. A large brook, which flows out of the first lake on this carry, poured into the Kennebec, just above their tents. Four hundred yards distant a large mountain, in shape a sugar loaf, appeared to rise out of the river, and turn it sharply eastward. All about them stood the forest primeval, dark, silent and mysterious. Under a leaden sky the north wind tossed the heavy boughs of the evergreens, sent showers of dying leaves from the half-naked oaks and maples, and slowly swayed the taller pines and beeches, which creaked and groaned in dismal lamentation at the touch of this forerunner of the winter. The rain still continued to fall with infrequent intermission. The next day Colonel Greene’s division came up, and two days later the third division made its appearance and joined its comrades who had preceded it in clearing the faint trails over which the bateaux must be taken.

The physical condition of the men, who were now but on the threshold of the most difficult and perilous stage of their journey, had begun to show serious deterioration as the natural result of the unfavorable weather. Cases of dysentery and other camp evils, which the bracing air might have cured, were augmented by long exposure in the water during the day and the cold, marrow-eating river-mists of night. Invalids were now frequently sent back along the line to the rear division, which, added to its greater load of provision, had to bear the full weight of every tale of woe. Nature, whose forest retreats and fastnesses the patriots were so boldly invading, had now turned her face from them, and taking advantage of their incessant strain and labor, with her champions, storm and cold, began ruthlessly to thin their ranks.

On October 12, when Lieutenant-Colonel Enos with the fourth division arrived at the Twelve Mile carrying place, out of the eleven hundred men who left Cambridge, the detachment could now muster only nine hundred and fifty. The loss had been chiefly occasioned by sickness and desertion, for there had been only one death – that of Reuben Bishop. But Captain Williams was so ill with dysentery that his life was despaired of. Arnold, meanwhile, left Norridgewock on the 9th and encamped with Captain McCobb that night on an island within two miles of Carratunk Falls. On the 11th he arrived at the Twelve Mile carry, and received from Lieutenant Church, who had, according to his orders, explored the route as far as the Dead River, his report and survey.