Contents

Contents

Bacon’s Rebellion was the first major uprising by American colonists against colonial leadership in the Thirteen Colonies, a hundred years prior to the beginning of the American Revolution.

Context and causes

In the mid-1650s, tobacco became an important cash crop in Virginia Colony.

Tobacco was the key to supporting oneself, and taxes were paid in the crops instead of cash. As a result, large plantation owners held the power in Virginia, especially given that only landowners were allowed to vote.

At the time, a lot of people’s indentured servitude was expiring. Many agreed to work for free for a certain period of time, in exchange for being able to travel to the New World, but in the mid-to-late 1600s, many of these people’s servitude was about to end.

Many of these newly freed people wanted to begin tobacco farming to support themselves, but found that getting started was extremely difficult.

Land was hard to come by, as it was mostly held by a small concentration of wealthy landowners. The problem was made worse by the fact that tobacco farming was extremely destructive to the soil, meaning that new farmland was in constant demand.

Those who did own land for small-scale farming came under pressure from increased taxes, as well as a sudden drop in colonial tobacco prices due to oversupply in the mid-1600s.

People wanted to expand westwards to capture new lands from the Native American population, to increase tobacco production. However, the governor of Virginia, William Berkeley, wanted to maintain friendly relations with the local tribes, and discouraged colonial expansion.

Berkeley was also controversial for his practice of issuing huge land grants to wealthy figures in the colonies, while also owning large tobacco plantations himself.

Summary of the Rebellion

Nathaniel Bacon was a recent arrival to Virginia, a wealthy, educated man who owned land on the frontier.

Despite his newcomer status, Bacon soon became involved in colonial politics. His social connections, wealth, and growing popularity among frontier settlers earned him a seat on the Governor’s Council in 1675.

He became a champion for the disgruntled settlers, favoring a much harsher government policy against the Native American population occupying fertile lands in Virginia.

In July 1675, a dispute between a Virginia merchant named Thomas Mathew and Doeg Indians led to a number of deaths on both sides. Mathew killed Indians attempting to steal livestock from his farm, and several settlers were killed, and fields destroyed, in the ensuing conflict.

Virginian forces attempted to hunt down the Doeg tribe, but accidentally attacked the allied Susquehannocks instead. From this point on, there were continuous raids from both tribes on local settlements.

Bacon wanted Virginia to lead an offensive force against the tribes to hunt them down, and claim their land. But Governor Berkeley instead prioritized defending the colony’s settlements from future raids.

After a series of attacks on colonial plantations in January 1676 which left scores of settlers dead, Bacon organized his own military force.

The militia was a diverse group, including poor whites, as well as Africans, both free and enslaved. Both groups were oppressed by the colonial elite and faced harsh economic and social conditions, and enslaved Africans may have hoped for a chance at freedom, in disrupting the colonial order.

Beginning in May, they attempted to hunt down the Susquehannocks, against the wishes of Berkeley. The Governor sent out a force to intercept the militia, and declared Bacon a traitor to Virginia.

Bacon’s forces were unable to locate the Susquehannocks, and instead massacred the Occaneechi tribe, killing at least 100 people.

After returning to Jamestown, Bacon was arrested, but quickly granted parole, promising to cease his attacks against the native population.

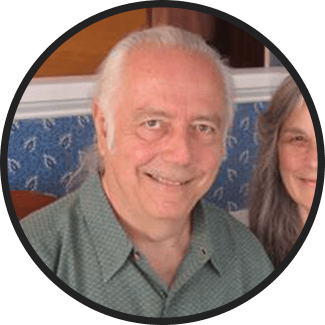

He was removed from his position in the Virginia General Assembly, but returned to the statehouse with his forces, demanding a military commission to deal with the Native Americans. This resulted in a direct standoff with Berkeley, during which the Governor dared Bacon to shoot him.

Ultimately, the Assembly heeded Bacon’s demands, passing “Bacon’s Laws” in late June 1676, which aimed to address the grievances of frontier settlers by reducing taxes, and expanding suffrage to non-landowning men.

However, after beginning to prepare his forces, Bacon discovered that Berkeley was attempting to create his own militia, to oppose Bacon’s troops.

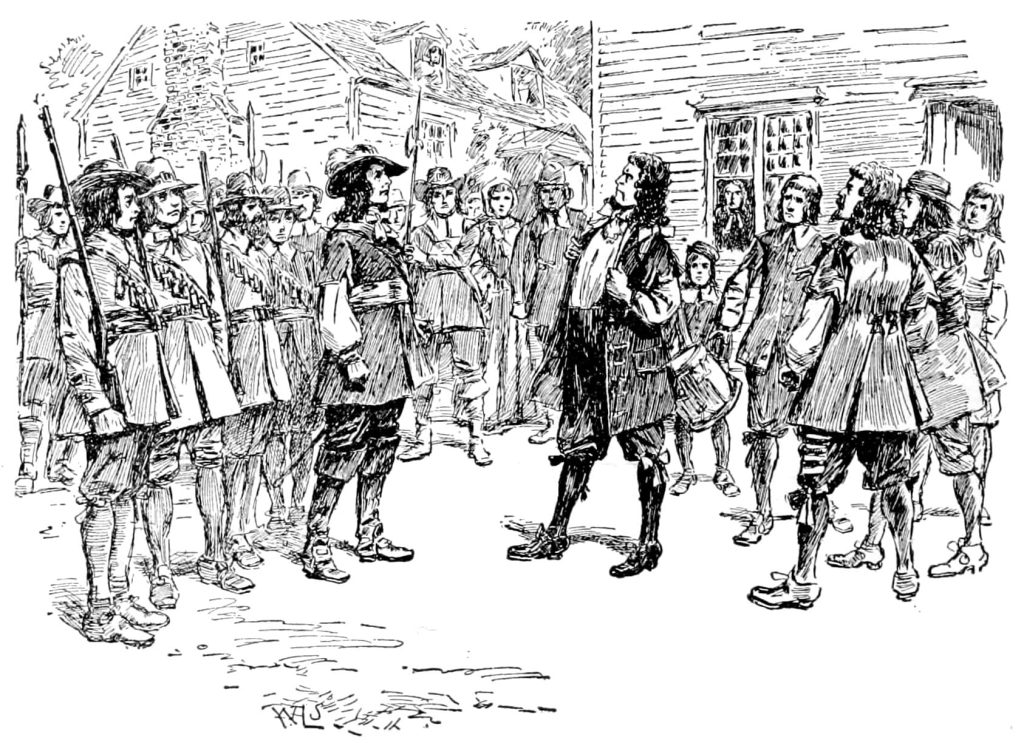

In July 1676, Bacon issued a manifesto accusing Berkeley of corruption, unfair taxation, and failure to protect the frontier, and his forces marched on Jamestown.

Berkeley fled the city, and by mid-September, after a brief conflict with the Governor’s forces, Bacon’s men entered Jamestown. They then burned the city to the ground on September 19, before leaving towards Yorktown.

Aftermath

The rebellion petered out quickly, as Nathaniel Bacon died suddenly of dysentery on October 26, 1676.

Without strong leadership, the rebel forces disintegrated. Berkeley returned to Jamestown with British reinforcements, and quickly retook control of the colony.

Harsh reprisals followed for those involved in the rebellion. Berkeley executed 23 rebel leaders from his return until early 1677, and also seized a significant amount of rebel property, some of which he allegedly kept for himself.

Berkeley was ordered to return to England but delayed his departure, instead choosing to seek retribution against the rebels, although many British officials called for leniency.

He was removed from his position as governor, and a royal commission was held, with the English Crown criticizing Berkeley for his severe response. However, he was suffering from illness, and died in England in July 1677.

Significance and effects

The rebellion led to increasing concern about future potential uprisings from formerly indentured servants who were struggling to make ends meet in the colonies.

As a result, the British accelerated their increasing reliance on African slave labor, as it was thought that slaves could be more easily subjugated, and were less likely to form a rebel alliance against the colonial governments.

Laws were passed to establish a clear racial divide, legally separating white and Black individuals, in an attempt to prevent lower social classes from uniting again to fight against the government.

Colonial elites gave poor whites small privileges and legal advantages over Black people, encouraging them to identify with the elite rather than unite with other oppressed groups.

Bacon’s Rebellion is often regarded as an important precursor to the American Revolution, as it was the first major uprising against British colonial power in the Thirteen Colonies.

However, the motivations behind Bacon’s Rebellion were quite different from later colonial acts of resistance against the British Crown.

While the American Revolution centered on broader ideals like self-governance, taxation without representation, and economic autonomy, Bacon’s Rebellion was largely a local and opportunistic conflict. It was driven by frustration with colonial leadership’s failure to address frontier settlers’ grievances, particularly their desire for land and protection.

Also, Bacon’s Rebellion was predominantly a struggle against the Native American population, which was often used as a scapegoat for a litany of problems the colonists were facing.

Unlike the Revolutionary War, Bacon’s Rebellion was unsuccessful, and did little to reduce social inequality in Virginia in the short to medium term.

Despite this though, the uprising did show that it was possible to successfully rebel against British rule, potentially emboldening future acts of resistance nearly 100 years later.