Contents

Contents

Quick facts

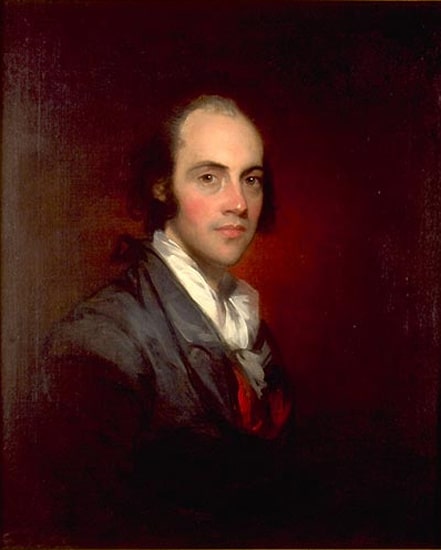

- Born: 6 February 1756 in Newark, New Jersey.

- Grandson of Congregationalist preacher and theologian Jonathan Edwards (1703—58).

- Prevented a duel between James Monroe and Alexander Hamilton, 1797.

- Nearly became president in the deadlocked election of 1800.

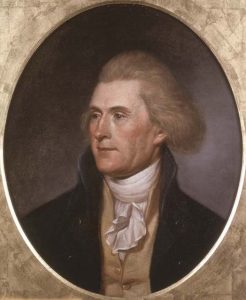

- Third Vice President of the U.S., 1801—05, serving under Thomas Jefferson.

- Killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel in 1804.

- Died: 14 September 1836 in Port Richmond, Staten Island, New York.

- Buried in at the Princeton Cemetery, Princeton, New Jersey.

Introduction

Aaron Burr — lawyer, politician, and vice-president of the United States — was born in Newark, New Jersey, on 6 February 1756. His father, the Rev. Aaron Burr (1715—57), was the second president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University); his mother was the daughter of Jonathan Edwards (1703—58), the well-known Congregationalist preacher and theologian.

In 1772 Burr graduated from the College of New Jersey. Two years later he began the study of law at Tappan Reeve in Litchfield, Connecticut — a celebrated law school conducted by his brother-in-law.

Participation in the Revolution

Soon after the outbreak of the Revolutionary War in 1775, he joined George Washington’s Continental Army in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He soon became part of Benedict Arnold’s expedition into Canada in 1775. On arriving outside of Quebec, he disguised himself as a Catholic priest and made a dangerous journey of some 120 miles through British lines to Montreal to notify General Richard Montgomery of Arnold’s arrival.

Burr served on the staffs of Generals Washington and Israel Putnam (1776—77). It was through his vigilance during the retreat from Long Island that he saved an entire brigade from capture. On becoming lieutenant colonel in July 1777, he assumed the command of a regiment. During the winter encampment at Valley Forge (1777—78), he guarded the Gulf,

a pass commanding the approach to the camp —and necessarily the first point that would be attacked. For the Battle of Monmouth (28-Jun-1778), Burr commanded a brigade in Lord Stirling’s division.

In January 1779 Burr was assigned to the command of the lines

of Westchester county, a region between the British post at Kingsbridge and that of the Americans about 15 miles to the north. In this district there was much turbulence and plundering by the lawless elements of both patriots and loyalists, as well as by bands of ill-disciplined soldiers from both armies. Burr rapidly restored order by establishing a thorough patrol system and rigorously enforcing martial law.

Law, marriage & politics

Due to ill-health, Burr resigned from the army in March 1779 and renewed the study of law. He was admitted to the bar at Albany in 1782 and following the evacuation by the British in 1783, he began to practice in New York.

In 1782 Burr married Theodosia Prevost (1746– 94), the widow of a British army officer who was 10 years older with five children. They had one daughter, Theodosia, in 1783. Burr was very happily married until his wife died prematurely at 47. He had an exceptional relationship with his daughter; but she was lost at sea in 1813.

Beginning in 1784 Burr was elected to a series of offices. He was a member of the New York State Assembly (1784—85), state attorney general (1789—91), U.S. senator (1791—97), and again a member of the assembly (1798—99; 1800—01). As national parties became clearly defined, he associated himself with the Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans. Although he was not the founder of Tammany Hall, he began the construction of the political machine upon which the power of that organization became based.

The election of 1800

In the election of 1800, Burr was placed on the Democratic-Republican presidential ticket along with Thomas Jefferson. Though it was understood that the party intended for Jefferson to be president, when each received the same number of electoral votes — defeating incumbent president John Adams, the outcome of the election was thrown to the House of Representatives. (This constitutional defect, where vice-president was the elector’s second presidential choice, was remedied when the 12th amendment was ratified in 1804.)

A powerful faction among the Federalists tried to secure the election for Burr, who despite being a Democratic Republican, said nothing — neither in favor of himself nor in favor of Jefferson. Partly because Burr made no effort to obtain votes in his favor, and partly because Hamilton, a Federalist and the enemy of Burr, ended up supporting Jefferson. Finally, after 36 ballots, the House elected Jefferson, who, forever after was cool to Burr.

Nevertheless, Burr became vice-president. As president of the Senate, his fair and judicial manner was recognized by even his bitterest enemies. And he helped to foster traditions quite different from those which have become associated with the speakership of the House of Representatives.

The duel with Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr had long been rivals at the New York bar. Also, Hamilton had opposed Burr’s aspirations for the Vice-Presidency in 1792 and had exerted influence over President Washington to prevent his appointment as brigadier-general in 1798 (at the time of the threatened war between the United States and France). In some measure he also prevented Burr from succeeding in the New York gubernatorial campaign of 1804.

Smarting under defeat and angered by Hamilton’s criticisms, Burr sent the challenge which resulted in the famous duel at Weehawken, New Jersey, on 11 July 1804. Hamilton was mortally wounded and died the next day.

After the duel

At the end of his term as vice-president (4-Mar-1805), broken in fortune, Burr was virtually an exile in his home state. Following his duel with Hamilton, he had been indicted for murder in both New Jersey and New York. So Burr relocated his unfulfilled ambitions to the southwest and became involved in the (so-called) conspiracy which continues to puzzle scholars today.

The earlier view that he planned a separation of the West from the Union has been discredited. Apart from the question of political morality, as a shrewd politician he would have recognized that the people of that section were too loyal to sanction such a scheme. It seems the object of his possibly treasonable correspondence with Anthony Merry and Carlos Martínez de Irujo, British and Spanish ministers at Washington, were to secure money and to conceal his real designs — which were probably to overthrow Spanish power in the Southwest and perhaps to also found an imperial dynasty in Mexico.

Arrested in 1807 on the charge of treason, Burr was brought to trial before the United States circuit court at Richmond, Virginia. The levers of the administration of Jefferson was against him, but he was acquitted by Jefferson’s cousin, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John Marshall. Immediately afterward he was tried on a charge of misdemeanor; on a technicality he was acquitted again.

Burr went abroad from 1808 to 1812, passing most of his time in England, Scotland, Denmark, Sweden, and France. He continued trying to secure aid for prosecute his filibustering schemes, but he was met with rebuffs — ordered out of England; in France, Napoleon refused to receive him.

Final years & legacy

Burr returned to New York in 1812 and spent the remainder of his life in the practice of law. In 1833 he married Eliza B. Jumel (1769—1865), a rich New York widow. Having lost much of her fortune in speculation, the two soon separated.

He died at Port Richmond in Staten Island, New York on the 14 September 1836.

Burr was unscrupulous, he could be insincere, and he was considered by many to be a notorious libertine. A brilliant lawyer, friend of the working class, he was pleasing in his manners, generous to a fault, and intensely devoted to his first wife and daughter. With intellect, skills, and ambition that matched or surpassed other Founding Fathers, he never wrote anything that resembled a political philosophy or expressed his ideas about what the United States should be. So despite his real contributions to the Revolution and the nascent republic, he is ultimately a fallen

founder.