Contents

Contents

Chapters

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Invasion of Canada is Planned

- Chapter 2: Benedict Arnold

- Chapter 3: The Expedition Sets Forth

- Chapter 4: The Ascent of the Kennebec

- Chapter 5: The March into the Wilderness

- Chapter 6: Flood, Famine, Desertion

- Chapter 7: Across the “Terrible Carry"

- Chapter 8: Arnold Saves the Remnant of His Army

- Chapter 9: Descending the Chaudière

- Chapter 10: Before Quebec

- Chapter 11: Montgomery Joins Arnold

- Chapter 12: The Investment

- Chapter 13: The Assault Is Planned

- Chapter 14: The Assault on Quebec

- Chapter 15: The Death of Montgomery

- Chapter 16: The Americans Stand Their Ground

- Chapter 17: Prisoners of War

- Chapter 18: A Hopeless Siege

- Chapter 19: The Campaign Fails

- Appendix

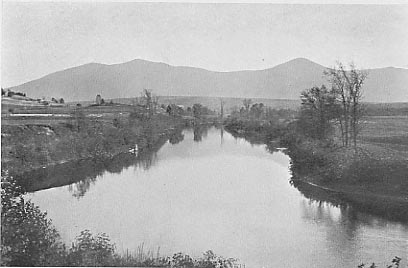

To the south and west of the spruce bog at the last portage of the Twelve Mile carry, there was a natural meadow of great extent covered with long grass, more than waist-high, which the men cut and used for covering at night, the army being inadequately supplied with tents and blankets. On the west, the meadow reached to the foot of the mountains several miles off, of which Mt. Bigelow – now so called – its summit thirty-eight hundred feet above sea-level, was the chief. Across the river to the north and east, at a distance of perhaps eight or ten miles, ran a range of high hills, the boundary of the valley of the Dead River on that side. The small creek already referred to formed a convenient harbor and landing place near the first camp of the army on the Dead River, there about sixty yards wide.

The Dead River here creeps down its course with a scarcely perceptible movement, its waters black, smooth, and overhung with thick grasses and bushes, by which, as the water was too deep for setting poles and they had few oars, some of the crews were obliged slowly and tediously to pull along the bateaux loaded still further with invalids, who were too weak to stand the fatigues of the march. The Mount Bigelow range, capped with snow, presented from this point of view its steepest and loftiest summit, its flank blackened by deep shadows (since the sun rises at this season directly behind it), and, forbidding and awe-inspiring, overhung the valley. As they advanced they found it lay directly between the army and home; it seemed gradually to close the road behind them and bar their retreat. Snow was falling lightly.

The original order of the divisions having been waived to save time, Colonel Greene, with the second division, passed the riflemen, still working on the roads, and made his way up the Dead River about twenty-one miles, arriving the 16th of October at the deserted wigwam of the suspected Indian spy Natanis, described by Steele’s scouts as “prettily placed on a bank twenty feet high, about twenty yards from the river, and with a grass plot extended around, at more than shooting distance for a rifle, free from timber and brushwood.” Three miles above it they went into camp.

The troops in the bateaux continued their snail-like progress, but most of the men crossed on foot the points of land between the serpentine windings of the river, which in this vicinity recoils upon itself so often that to advance directly ten miles one must frequently paddle or pole nearly twice that distance by water. The Mount Bigelow range held them like a lodestone; it seemed impossible to escape its shadow – often they seemed to be again approaching it. During the day they had carried seven rods around low falls, now known as “Hurricane Falls.” The carry at these falls was a convenient half-way camp to Natanis’s wigwam, and Dearborn’s company, and probably the whole third division also, camped there on the 16th. Next day Dearborn’s men joined Colonel Greene’s division. Arnold was encamped at the same place where Greene’s men were resting and waiting for the next division to come up with provisions, for theirs were nearly exhausted. He had arrived at three o’clock in the morning. They were employing the time in making up cartridges, filling their powder horns, and looking to their accoutrements. There seems to have been no apprehension of any Indian attack, and no extraordinary precautions were taken to avoid surprise, beyond the scouting parties mentioned – not even regular guard-mounting – but Arnold wished to use every moment of time to some advantage, and to keep the men out of mischief. The two oxen driven across the Twelve Mile carry had been slaughtered at the first encampment on the Dead River on the18th, and five quarters were sent forward to this part of the detachment in advance. This was the last fresh domestic provision, thereafter the whole army must rely on flour, pork and whatever they could forage from the wilderness.

The inequality in the distribution of the provisions among the different companies, resulting from the causes mentioned, had now conspicuously appeared. Topham’s and Thayer’s companies,of Greene’s division were brought as early as the 16th, to half allowance, and on the 17th, had only five or six pounds of flour per man. Accordingly, Arnold, much concerned, sent back Major Bigelow with twelve bateaux and ninety-six men, with orders to draw upon. Lieutenant Colonel Enos in the rear, for all the provisions he could spare, at the same time writing a letter to Enos, in which the extremity of the foremost divisions was clearly set forth.

On the 17th also Morgan’s division passed Greene’s encampment and went on for Chaudière pond. The weather on the 18th set in again very rainy, and the third division having now joined Greene’s, both remained here till the afternoon of the 19th, when the rain ceased. Then Meigs with his division marched on (for they had still a fair quantity of provisions), under orders to push for the Height of Land and, while awaiting the rear there, to make up cartridges and furnish a number of pioneers to clear the portages. They continued their route up the river five miles, and encamped on the north bank. That afternoon they passed three small falls; the river current, except at the falls, continued gentle. Thus we find that the riflemen had resumed their position at the head of the detachment, and were now only a few miles above the third division, becoming second in the line.

On October 19 Arnold closely followed Meigs’s division and two days later he overtook the riflemen, but as Morgan’s encampment was bad, he proceeded one mile higher up the river and camped about eleven that night, very wet and much fatigued. It had begun to rain again, and though the riflemen made twenty miles on the 18th, having only one short carrying place to surmount, the rain then drove them into their tents and confined them there the greater part of the next four days, during which they only advanced five miles further. They were the more readily induced to delay, as they were nearly out of provisions and were counting upon the rear divisions to bring them supplies.

Greene’s division meanwhile had packed the cartridges they had made in casks and loaded their bateaux, and then, in enforced idleness, their rations daily more insufficient, awaited anxiously the supplies Major Bigelow and his detail had been sent to bring up. This division had now been delayed for five or six days to no purpose, and had fallen to third place in the column. Their impatience was not lessened by their empty stomachs and the rapid disappearance of the scanty provender which remained to them. The third division, holding the second place in the line, made steady progress, in spite of the thick and rainy weather, and were fortunate in finding the water plentiful, the current gentle and the portages few and short.

But as the bateaux, when fully loaded, could carry only three men each, this long and rough march was accomplished by most of the men on foot. As they forced their way through thickets and fell over logs and pitfalls, climbed over blow-downs and scrambled over the rocks, they reduced their clothing to tatters. The torrents of rain saturated and stained their uniforms, blankets and camp equipment, and rusted their firearms and tools. Sometimes the underbrush and thickets were so dense that they saved time and labor by wading in the shoals under the banks of the river. The rough bed of the stream, which was full of stones and boulders, tempted many to keep their shoes on while they waded, and moccasins or army shoes worn on wet ground or ‘under water for many days were soon almost useless. The huge fires they built at night were not sufficient to warm and dry them before the teeth of the most robust were chattering, and whole companies, as the chill of nightfall drew on, shivered as if with the ague. It was not a week before many of the improvident who had relied on one pair of shoes were barefoot.

During the morning of the 21st the rain increased in violence, the river began noticeably to rise, and the wind, swinging to S. S. W., threatened a hurricane. Every division of the detachment, except that of the riflemen, was buffeting the storm as best it might; and more or less successfully according to the character of the ground where it happened to be. As darkness came on the hurricane was fairly upon them, and trees which overhung the banks were blown down or uprooted in every direction, rendering further passage as dangerous as it was difficult. The risk of encamping in the forest was great, and the men selected the most open places they could find, but many could not use their tents for fear of falling trees, and it was quite impossible to, keep up their fires in such a deluge of rain. So the night passed in the midst of perils and discomforts which must have tried the most cheerful and courageous spirit.

Many had no shelter whatever from the furious storm save such bark huts as they had time hurriedly to construct.

As morning approached the encampments became flooded and untenantable. The river had already risen three feet. It was no longer “dead”; it was wonderfully and fearfully alive with rushing water, drift and debris. Daylight revealed several of the bateaux which had been hauled up, sunken alinost out of sight. Barrels of powder, pork and other supplies had been washed off the bank and carried down stream. The storm abated, but the river continued to swell in volume. It finally rose to the unparalleled height of nine feet, overflowed its banks, spread through the forest intervale in low places for a mile or more on either side, and from a freshet became a flood, which dashed over the falls and ledges with a five-mile-an-hour current. Only two similar floods, if local tradition can be trusted, have occurred since this of 1775. All the small tributary rivulets (and they were not a few) were increased to an enormous size. The few guides became confused, and the copies of Montressor’s map which some of the officers had were therefore worse than useless. The footmen were obliged to trace these false rivers for miles till some narrow place presented a ford, and even then were often able to cross only by felling large trees for foot-bridges.

No longer obliged to carry the bateaux over portages, the crews floated and hauled them against the current through the cuttings in the woods made by the riflemen. Progress was more snail-like than ever. The second division advanced only six miles, the third only four. Lieutenant Humphreys and his whole boat’s crew were overturned, and lost everything except their lives-“with which they unexpectedly escaped.”

Smith’s company of riflemen who were encamped on a bank eight or ten feet above the river, two or three miles below Ledge Falls, the most difficult cataract on the Dead River, on the night of the tempest, had fared even worse than the others, for they had reached the foothills of the Height of Land. The river rose so suddenly in the darkness that the first notice of their danger was towards morning, when the water swept under their shelters and carried away most of their provisions and camp equipment.

Arnold has been accused by Burr of not sharing the privation of his men on this expedition. Certainly he fared no better than the rest on this night, for he saved himself only by sacrificing his baggage, and retreated to a hillock just above the flood, where he remained till morning in great discomfort and anxiety.

As soon as there was daylight enough to enable them to see their way in the forest, the riflemen resumed their march. Deceived by the overflow, they mistook a western branch of the Dead River – which meets it a few miles from the encampment from which they had just been driven – for the main stream.

Some of them journeyed up this branch seven miles before they discovered their mistake and found an opportunity to cross. The country round about is much cut up with ponds, rivulets, steep hills and bogholes, and when overflowed was a puzzling labyrinth for the most experienced woodsman. The snagging and spotting of Steele’s and Church’s men, owing to the freshet, was of little avail, nor was the compass of much service, for few, if any, of the captains had received the courses and distances on the river. The freshet and flood could not have been foreseen by their commander. But the riflemen’s ill-luck brought them some advantage, for on this misleading stream they discovered the wigwam of Sabattis, brother of Natanis, and, hidden in bark cages in the tree-tops, his kettle, cooking utensils and some dried meats. What they could not consume they destroyed, and crossing the stream made a bee-line across the land between them and the Dead River.

The footmen of the third division, falling into the same error, got four miles on their way up this stream, when they were set right by a boat’s crew despatched by Arnold, who had foreseen their mistake and predicament. They then made the best of their way to the main channel, crossing the branch on a tree. As they approached a fall which, with the river at its usual height, is only four feet, in the midst of a channel not much more than fifty feet wide, they perceived a cataract three times the width of the real channel, and beheld the crews of their boats making a hopeless struggle to stem the current. Five or six were already upset and lost, with all their contents, a quantity of clothing, guns and provisions, and “a considerable sum of money destined to pay off the men.” The riflemen were to be seen seated in shivering groups along the bank below the falls, gazing longingly upon the opposite bank, where were landed such of their bateaux, provisions and camp equipage as had escaped the flood.

These falls – Ledge Falls as they are called – were the most formidable they had encountered on the Dead River. Rocky ledges on either side rose to a height of thirty or forty feet, like the open floodgates of a gigantic dam, and the river sweeps down a narrow gorge between them, as through a sluiceway, with a strong current even when the waters are low. The first of the long chain of lakes to be crossed before coming to the Height of Land lies hardly eight miles distant, and these, shut in by precipitous mountains, form natural reservoirs of which the Dead River is the outlet. The valley narrows as it reaches these lakes, and the intervale is cut up by steep hills and deep ravines. The circuits the army was obliged to make to avoid the overflowing of the river became wider and more fatiguing, especially as, owing to their separation from their bateaux, the men were without food, or shelter except such provision from the previous day’s rations as the more prudent might have husbanded in their knapsacks or pockets.

Greene’s division was in perhaps the worst plight of all. Bigelow’s party had returned, but with only two barrels of flour by way of provisions, having found it impossible to get more from Colonel Enos. Discouraged by the scarcity of supplies, and the additional hardships the freshet compelled them to undergo, the men were still further shaken by the sight of returning boats, laden with invalids from Morgan’s and Meigs’s divisions, who assured them of the hopelessness of any further progress against the obstacles which nature had set in their path, and exhorted them to turn back and save their own lives at least. But the brave fellows showed no signs of faltering, and pressed forward dauntlessly, though with slow and toilsome steps, into the wilderness, – not like the Light Brigade, with the inspiring note of bugles and the cheers of an army, fired with the glorious inspiration of a cavalry charge, but yet more heroically, into the very jaws of a slow and terrible death by famine, at the mercy of wolves and wild beasts, into a country held by an enemy. Reduced to half a pint of flour per man, even the salt washed out of their boats, they awaited their commander’s arrival, to consult over their desperate condition.

A council of officers, over which Arnold presided, had been held at the camp of the riflemen and the third division below the falls the evening before, and in accordance with its resolve, Captain Handchett, with fifty-five men, had hurried on by land for Chaudière pond and the French settlements to obtain supplies. The sick and those unfit for duty were sent back, with an officer and a few well and able-bodied men to care for the worst cases, to Colonel Enos, who was directed to give them such comfort as he could, and expedite their return to the Kennebec and Cambridge.

On the 24th of October the two leading divisions moved again. It was snowing gently, and daylight on the 25th disclosed two inches of snow on the ground. The ground was difficult and progress slow, but on the 26th Meigs’s men carried their bateaux, now few in number, out of the river and launched them in the first of a long chain of lakes, which led to the foot of the Boundary Mountains, to them become as the Promised Land to the long-wandering children of Israel. They passed over the first lake two miles to a narrow gut two rods over, then poled up a narrow strait one and a half miles long; then passed over a third lake, three miles; then up another connecting strait, half a mile; and at last entered a fourth lake only a quarter of a mile wide. Afternoon found them poling and dragging up a narrow, tortuous gut, three or four miles in length, running through a desolate swamp. At evening they came to a portage fifteen rods across, and there encamped. Arnold was in advance with Handchett’s detail, camped several miles beyond.

On the 27th Meigs’s men crossed the carrying place to a lake half a mile over; made another carry of one mile; then passed across a little pond one-quarter of a mile wide; then a portage of forty-four rods to another lake two miles wide. They crossed this and came to the Height of Land and the long carry of four and one-half miles to the Chaudière waters. Here they received orders to abandon their bateaux, and to transport only one for each company across the mountainous portage. But Morgan, who preceded them, unwilling to leave the spare ammunition of the detachment which had been intrusted to his company of Virginians, and foreseeing that when the great task was once accomplished and they should reach the Canadian waters his men would thank him for their punishment, carried over seven of his boats and launched them in the river running down seven miles from the Height of Land to Chaudière Lake. This stream was then confused by many with the true Chaudière. It is now called the Seven Mile stream or Arnold’s River. Hendricks’s men also attempted this, and persisted until their shoulders were so bruised and chafed that they could not bear a touch without shrinking. They had carried most of their bateaux to the top of the ridge, but finally abandoned all but one before they reached the Seven Mile stream. Morgan’s all-enduring men are said to have worn the flesh from their shoulders in the gallant execution of his orders.

Morison, one of Hendricks’s riflemen, describes this portage, which he says the army denominated “the terrible carrying place,” as a considerable ridge covered with fallen trees, stones and brush. “The ground adjacent to the ridge is swampy, plentifully strewed with old dead logs, and with everything that could render it impassable. Over this we forced a passage, the most distressing of any we had yet performed; the ascent and descent of the hill was inconceivably difficult. The boats and carriers often fell down into the snow; some of them were much hurt by reason of their feet sticking among the stones. Attempts were made to trail them over, but there was too much obstruction in the way. Besides, we were very feeble from former fatigues and short allowance of but a pint of flour each man per day for nearly two weeks past, so that this day’s movement. was by far the most oppressive of any we had experienced.”

The bateaux of Meigs’s division were hauled up during the afternoon of the 27th, and all but six for each company abandoned; the provisions distributed and everything got in readiness to cross the “terrible carry” over the Boundary Mountains. Most of their supply of powder was found to be ruined by dampness, and was accordingly destroyed.

We must now return to the forlorn camp of Greene’s division, near Ledge Falls, where events of the utmost moment were in progress. The desperate straits to which Greene’s men were reduced by the failure of their provisions have already been alluded to, and we have seen that Major Bigelow’s party was able to procure only two barrels of flour from the rear guard with which to relieve their comrades’ necessities. As a matter of fact, supplies were running low with Enos’s division, as well as with the others. Though they were supposed to be bringing up the bulk of the army’s provisions, they had met with the same misfortunes which had overtaken the rest of the detachment. Leaky bateaux, accidents on the portages, and finally the great freshet, had depleted the reserve supply, until the officers of the rear guard found themselves in possession of what they considered hardly enough to take their own men across the divide. The urgent appeals of Greene fell, therefore, on unwilling ears; even Arnold’s peremptory orders could induce them to part with only a small part of their stores.

In this situation of affairs a settlement of the questions at issue became necessary, and a council of war was called to meet at Greene’s camp, the officers from his own and Enos’s divisions being summoned. From the first it was apparent that the latter were determined to turn back, the insufficiency of the provisions and the increasing difficulties of the undertaking proving to be unanswerable arguments to their minds. By the casting vote of Colonel Enos himself, who gave his voice for going forward, it was voted not to retreat; but no sooner was this decision reached than the three captains of his division, McCobb, Williams and Scott, held an informal council of war among themselves. At its conclusion they announced that they would not lead their men into the almost certain starvation and death they saw as the only issue of this reckless march into a hideous wilderness, but would retire at once to the Kennebec settlements. Upon this Colonel Enos decided, with profusely expressed regret, though apparently without much reluctance, that his duty lay with his division, and that if it determined to return to New England, his place was at the head of its columns.

The officers of Greene’s division, although they had borne such sufferings and hardships as those of the rear guard had not even witnessed, were still unanimous in their determination to press forward, and their indignation with Colonel Enos and his subordinates was profound. Reproaches and entreaties were alike ineffectual in altering these officers’ minds, however, and two more barrels of flour were all the additional supply that the timorous rear guard could be induced to surrender to their half-starving comrades.

These are the quaint words in which Dr. Isaac Senter, the surgeon with Greene’s division, describes the proceedings, and voices the exasperation with which they inspired him: “They (Colonel Enos and his officers) came up before noon, when a council of war was ordered. Here sat a number of grimacers, -melancholy aspects who had been preaching to their men the doctrine of impenetrability and non-perseverance, Colonel Enos in the chair. The matter was debated upon the expediency of proceeding on to Quebec, the party against going urging the impossibility, averring the whole provisions, when averaged, would not support the army five days. After debating the state of the army with respect to provisions, there was found very little in the division camped at the Falls (which I shall name Hydrophobus); the other companies not being come up, either through fear that they should be obliged to come toa divider, or to show their disapprobation of proceeding any further. The question being put whether all to return or only part, the majority were for part, only, returning. Part only of the officers of those detachments were in this council.

Those who were present and voted were: For proceeding: Lieutenant-Colonel Enos, Lieutenant-Colonel Greene, Major Bigelow, Captain Topham, Captain Thayer, Captain Ward.

For returning: Captain Williams, Captain McCobb, Captain Scott, Adjutant Hyde, Lieutenant Peters.

According to Colonel Arnold’s recommendation, the invalids were allowed to return, as also the timorous. The officers who were for going forward requested a division of the provisions, and that it was necessary they should have the far greater quantity in proportion to the number of men, as the supposed distance that they had to go ere they arrived into the inhabitants was greater than what they had come, after leaving the Kennebec inhabitants. To this the returning party (being pre-determined) would not consent, alleging that they would either go back with what provisions they had, or if they must go forward, they’d not impart any. Colonel Enos, though (he) voted for proceeding, yet had undoubtedly pre-engaged for the contrary, as every action demonstrated. To compel them to a just division, we were not in a situation, as being the weakest party. Expostulations and entreaties had hitherto been fruitless. Colonel Enos who more immediately commanded the division of returners, was called upon to give positive orders for a small quantity, if no more. He replied that his men were out of his power, and that they had determined to keep their possessed quantity whether they went back or forward. They finally concluded to spare (us) 2 1/2 barrels of flour, if determined to pursue our destination, adding that we should never be able to bring (in) any inhabitants. Through circumstances we were left the alternative of accepting their small pittance, and proceed, or return. The former was adopted with a determination to go through or die. Received it, put it on board our boats, quit the few tents we were in possession of, with all other camp equipage, took each man his duds to his back – bid them adieu, and away – passed the river, passed over falls, and encamped.”

Oh, why was not Arnold of this momentous council, which in the midst of the wilderness, shivering in the driving snowstorm, decided the fate of the Expedition, and left Canada to Great Britain! Oh, for his strong hand, his powerful invective, his earnest persuasion! Who can doubt the stinging rebuke and withering scorn with which he would have lashed those disobedient officers, who, contrary to express commands, contrary to the decision of a general council of war, acting on their own private agreement, were ready to desert their comrades of the advance, and abandon an enterprise the failure of which would cast the deepest gloom over the cause in which their country had embarked.

Arnold on this day, the fatal 25th of October, was battling with the elements on the lakes. In the midst of the snowstorm the wind blew a gale, the seas on the lakes became formidable and his bateaux had frequently to be run ashore and bailed. He had missed his guides and was not able to camp until near midnight, and then he did not know whether he was on the right trail or not. So it was that an express despatched by Greene telling of this serious situation, returned without finding him. How slender, and at the time how invisible, are the links in the chain which bind together the great events of history, and unite or divide an empire! From the failure of this courier to reach Arnold may be traced Enos’s defection and return, the failure of the repulse before Quebec, the retreat from Canada, and the loss of British America to the American Union.

But under date of October 24, Dead River, 30 miles from Chaudière pond, Arnold had written this letter to Lieutenant-Colonel Enos: “Dear Sir: – The extreme rains and freshets in the river have hindered our proceeding any further. When I wrote you last, I expected before this to have been at Chaudière. I then wrote to you that we had about twenty-five days’ provisions for the whole. We are now reduced to twelve or fifteen days, and don’t expect to reach the pond under four days. We have had a council of war last night, when it was thought best, and ordered, to send back all the sick and feeble with three days’ provisions, and directions for you to furnish them until they can reach the Commissary in Norridgewock; and that on the receipt of this, you should proceed with as many of the best men of your division as you can furnish with fifteen days’ provisions, and that the remainder, whether sick or well, should be immediately sent back to the Commissary, to whom I wrote to take all possible care of them. I make no doubt that you will join me in this matter, as it may be the means of preserving the whole detachment and of executing our plan without moving by great hazard, as fifteen days will doubtless bring us to Canada. I make no doubt you will make all possible expedition.

I am, dear Sir,

Yours,

B. ARNOLD.”

On the very same date, Arnold wrote to Greene telling him to send back the sick and feeble, to proceed with his best men, and fifteen days’ provisions, and adding – “Pray hurry on as fast as possible.”

Greene marched on. But Enos’s division, and according to Lieutenant Buckmaster’s statement about one hundred and fifty invalids from other divisions, turned their backs on their comrades and began to make the best of their way home to Cambridge.

The news of Enos’s defection, as Captain Dearborn wrote in his journal, “disheartened and discouraged the men very much. … But, being now almost out of provisions, we were sure to die if we attempted to turn back, and we could be in no worse situation if we proceeded on our route. Our men made a general prayer that Colonel Enos and all his men might die by the way or meet with some disaster equal to the cowardly, dastardly and unfriendly spirit they disclosed in returning back without orders in such a manner as they had done, and then we proceeded forward.”

In a similar tone, Sergeant Stocking, who was far in the advance with Arnold and Captain Handchett, wrote: “To add to our discouragement, we received intelligence that Colonel Enos, who was in our rear, had returned with three companies, and taken a large share of provisions and ammunition. These companies had constantly been in the rear, and, of course, had experienced much less fatigue than we had. They had their paths cut and cleared by us; they only followed, while we led. That they, therefore, should be the first to turn back, excited in us much manly resentment. … Our bold though inexperienced commander discovered such firmness and zeal as inspired us with resolution. The hardships and fatigues he encountered he accounted as nothing in comparison with the salvation of his country. So, another volunteer, expressing the universal disgust with which the conduct of Enos and his captains was regarded by those who persevered, wrote: ” May shame and guilt go with him, and wherever he seeks a shelter, may the hand of justice shut the door against him!”

The court martial held in Cambridge December 1, 1775, acquitted Lieutenant-Colonel Enos with honor, but did not hush the popular outcry. So persistent was this that in May, 1776, Enos was forced to defend his reputation in print by presenting an address to the public, containing the evidence offered to the court with the certification of the president, General John Sullivan, and a further endorsement of his general character and ability as an officer, signed by many prominent officers of the Continental army. It must be remembered, however, that no evidence from the men who suffered by Enos’s conduct was submitted to the court – indeed, there was no evidence obtainable, at that time, from Arnold and the officers who advanced. The decision of the court appears to have been based entirely on the testimony of Enos and his officers, who would share with him any ignominy attached to the retreat. Lieutenant-Colonel Enos, long mouldered into dust, cannot resume his defense, but is it not to be regretted that the men who marched forward only to starve to death or feed the wolves, could not have appeared before the court? Their wan specters could have asked Enos some troublesome questions.

On what precedent did he reverse the decision of a council of war by the separate and subsequent vote of a minority? When Captain McCobb testified before that court martial that it was agreed at a council of war that Greene’s division should advance and Enos’s division return, did he speak the truth? When he and Adjutant Hyde declared that Enos’s division left Greene’s with five days provisions, did they agree upon a lie? Why was no base of supplies established at the Twelve Mile carry, and boats with guards stationed on the ponds of that carry, in accordance with Arnold’s repeated orders -especially if Enos felt so sure that those who went forward must fail?

But, on the other hand, had Enos ordered his division to advance, perhaps the men of his own division – some of whom would undoubtedly have perished -would also have risen to haunt him, and their specters might have been still more numerous and implacable. Arnold had last written, “proceed with as many of the best men as you can furnish with fifteen days’ provisions, and send back the rest, whether sick or well, to the commissary.” Circumstances over which Enos had no control rendered the precise execution of this order an impossibility. Was he not, then, justified in using his discretion? The impartial reader must put himself in Enos’s place and decide for himself whether he would have chosen the spirits of the soldiers in advance, or those of his own division, for visitants. It was an occasion which “tried men’s souls” more than an occasion which tried their judgment.