Contents

Contents

Quick facts

- Born: 17 January 1706 in Boston, Massachusetts.

- Though associated with Philadelphia, Benjamin Franklin was born and raised in Boston. He did not arrive in Philadelphia until he was 17 (6-Oct-1723).

- In addition, Franklin also spent some 28 years abroad, in England and France, at various times throughout his life.

- Deborah Read, his future wife, saw him on the first day he arrived in Philadelphia with a roll of bread “under each Arm, and the eating of the other [third one].” They did not marry until 7 years later (1-Sep-1730).

- Poor Richard’s Almanack, published each year from 1732 to 1757, made Franklin a very wealthy man. He himself estimated (in his Autobiography) that it sold “annually near ten Thousand” copies.

- Besides his printing business, Franklin was also postmaster of Pennsylvania beginning in 1737. In 1753, he became one of two deputy postmasters of North America, a post he held for 20 years.

- By retiring from the printing business in 1748 (in a lucrative arrangement with his foreman), Franklin had the leisure time to study, experiment, and invent. His subsequent work and publications on electricity made him the most famous man in the North American colonies and a celebrity in Europe.

- Franklin was always a “civic organizer” — initiating street paving, lamp lighting, firefighting, book-lending, and more — and was involved in elective politics from 1751 onward. So his involvement in the American Revolution was natural, but not inevitable. But for events, he may have chosen to stay in England, which is where he was from 1764 to 1775.

- Franklin returned to Philadelphia in 1775, was elected to the Second Continental Congress, made small corrections to The Declaration of Independence, signed it, and in December 1776 was sent to France as U.S. Commissioner to plead the American cause. He stayed there throughout the war, extracting much-needed money and supplies from the French, despite little American success on the battlefield.

- Franklin owned two slaves, George and King, who worked as his personal servants.

- Died: 17 April 1790 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

- Buried at Christ Church Burial Ground, Philadelphia.

Introduction

Benjamin Franklin, American diplomat, statesman, and scientist, was born in a house on Milk Street — opposite the Old South Church — in Boston, Massachusetts in 1706. He was the tenth son of Josiah Franklin, and the eighth child and youngest son of ten children borne by Abiah Folger, his father’s second wife. Born at Ecton in Northamptonshire, England, the elder Franklin’s strongly Protestant family can be traced back nearly four centuries. He had married young and migrated from Banbury to Boston in 1685.

The autodidact

Benjamin Franklin could not remember when he did not know how to read. At eight years old he was sent to Boston Grammar School, destined by his father for the church as a “tithe” of his sons. But it was not to be. He spent a year there and then a year in a school for writing and arithmetic. When he was ten, he was removed from school to assist his father in his business of tallow chandler

(candle maker) and soap boiler. In his 13th year he was apprenticed to his half-brother James, who was establishing himself in the printing business, and who, in 1721. started one of the earliest newspapers in America, the New England Courant.

Franklin’s tastes had at first been for the sea rather than the pulpit; now they inclined to intellectual pleasures. At an early age he had made himself familiar with The Pilgrim’s Progress, with John Locke’s, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, and with The Spectator. Thanks to his father’s excellent advice, he gave up writing doggerel verse (much of which had been printed by his brother and sold on the streets) and turned to prose composition. His success in reproducing articles he had read in The Spectator led him to write an article for his brother’s paper, which he slipped under the door of the printing shop with no name attached. It was printed and attracted some attention. After repeated successes of the same sort, Franklin threw off his disguise and contributed regularly to the Courant.

The journalist

When, after various journalistic indiscretions, James Franklin in 1722 was forbidden to publish the Courant, Benjamin Franklin’s name appeared as publisher instead — and received with much favor — chiefly because of the cleverness of his articles signed Dr Janus.

But Franklin’s management of the paper and his free-thinking displeased the authorities. In addition, the relationship between the two brothers also soured — possibly, as Franklin himself thought, because of his brother’s jealousy of his superior ability.

So Franklin quit his brother’s employ. He first made his way to New York City, then on 6 October 1723 he arrived in Philadelphia and soon found a job with a printer named Samuel Keimer. A rapid composer of type and a workman of resource, Franklin was soon recognized as the master-spirit of the shop.

Recognizing his talent, the governor of Pennsylvania, Sir William Keith (1680—1749), urged Franklin to start his own business. When Franklin unsuccessfully appealed to his father for the means to do so, Keith promised to furnish him with what he needed for the equipment of a new printing office and sent him to England to buy the materials. Keith had repeatedly promised to send a letter of credit by the ship on which Franklin sailed, but on arrival in England, no such letter was found.

Franklin reached London in December 1724 and found employment first at Palmer’s, a famous printing house in Bartholomew Close, and afterwards at Watts’s Printing House. At Palmer’s he had set up a second edition of William Wollaston’s Religion of Nature Delineated. But to refute this book and to prove that there could be no such thing as religion, he wrote and printed a small pamphlet,A Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity, Pleasure and Pain — which brought him some curious acquaintances, and of which he soon became thoroughly ashamed.

After a year and a half in London, Franklin was persuaded by a friend, a Quaker merchant named Denham, to return with him to America and engage in mercantile business. He gave up his printing work and returned to North America. (Franklin had so many skills, his feats as a swimmer being one of them. A few days before sailing he received a tempting offer to remain and give lessons in swimming —and he might have consented had the overtures been sooner made.

)

He reached Philadelphia in October 1726.

However, a few months later, Denham died, and Franklin was induced by large wages to return to his old employer Keimer. But they quarrelled repeatedly and Franklin thought of himself as ill-used and kept only to train apprentices until they could in some degree take his place.

In 1728 Franklin and Hugh Meredith, a fellow-worker at Keimer’s, set up in business for themselves (with capital furnished by Meredith’s father). In 1730 the partnership was dissolved, and Franklin, through the financial assistance of two friends, secured the sole management of the printing house.

In September 1729, he bought, at a merely nominal price, The Pennsylvania Gazette, a weekly newspaper which Keimer had started nine months before (to defeat a similar project of Franklin’s) — and which Franklin oversaw until 1765. Franklin’s superior management of the paper, his new type, some spirited remarks

on the controversy between the Massachusetts Assembly and Governor Burnet, brought his paper into immediate notice, and his success both as a printer and as a journalist was assured and complete.

The community organizer

In 1731 Franklin established in Philadelphia one of the earliest circulating libraries in America. In 1732 he published the first of his Almanacks under the pseudonym of Richard Saunders. These “Poor Richard’s Almanacks” were issued for the next 25 years with remarkable success — with annual sales averaging 10,000 copies — far exceeding the sale of any other publication in the colonies, and making Franklin a rich man. Beginning in 1733 Franklin taught himself enough French, Italian, Spanish and Latin to read these languages with some ease. In 1736, he was chosen clerk of the General Assembly — and served in that capacity until 1751.

In 1737 he was appointed postmaster at Philadelphia, and about the same time he organized the first police force and fire company in the colonies. In 1749, after he had written Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania, he and twenty-three other citizens of Philadelphia formed themselves into an association for the purpose of establishing an academy — opened in 1751, chartered in 1753 — which eventually became the University of Pennsylvania. In 1727 he organized a debating club, the “Junto,” in Philadelphia, and later he was one of the founders of the American Philosophical Society (1743). He took the lead in the organization of a militia force, the paving of the city streets, improved the method of street lighting, and assisted in the founding of a city hospital (1751). In brief, he initiated nearly every measure or project for the welfare and prosperity of Philadelphia undertaken in his day.

The politician and diplomat

In 1751, Franklin became a member of the General Assembly of Pennsylvania, in which he served for 13 years. In 1753 he and William Hunter were put in charge of the postal service of the colonies. He visited nearly every post office in the colonies and increased the mail service between New York and Philadelphia from once to three times a week in summer, and from twice a month to once a week in winter. By the time he left in 1774, not only had the postal service been brought to a high state of efficiency, but it was also a financial success for Franklin.

When war with France appeared imminent in 1754, Franklin was sent to the Albany Convention, where he submitted his plan for colonial union. When the home government sent over General Edward Braddock with two regiments of British troops, Franklin undertook to secure the requisite number of horses and wagons for the march against Fort Duquesne; he became personally responsible for payment to the Pennsylvanians who furnished them.

Notwithstanding the alarm occasioned by Braddock’s defeat, the old quarrel between the proprietors of Pennsylvania and the Assembly prevented any adequate preparations for defense; with incredible meanness

the proprietors had instructed their governors to approve no act for levying the necessary taxes, unless the vast estates of the proprietors were by the same act exempted. So great was the confidence in Franklin in this emergency, that early in 1756 the governor of Pennsylvania placed him in charge of the northwestern frontier of the province, with power to raise troops, issue commissions and erect blockhouses. Franklin remained in the wilderness for over a month, superintending the building of forts and watching the Native Americans.

First diplomatic mission to England

In February 1757 the Assembly, finding the proprietary obstinately persisted in manacling their deputies with instructions inconsistent not only with the privileges of the people, but with the service of the crown, resolv’d to petition the king against them,

and appointed Franklin as their agent to present the petition. He arrived in London on 27 July 1757, and shortly afterwards, when, at a conference with Earl Granville, president of the council, the latter declared that the King is the legislator of the colonies.

Franklin in reply declared that the laws of the colonies were to be made by their assemblies, to be passed upon by the king, and when once approved were no longer subject to repeal or amendment by the crown. As the assemblies could not make permanent laws without the king’s consent, neither could he make a law for them without theirs,

he said.

These opposite views distinctly raised the issue between the home government and the colonies. As to the proprietors, Franklin succeeded in 1760 in securing an understanding that the Assembly should pass an act exempting from taxation the un-surveyed waste lands of the Penn estate, the surveyed waste lands being assessed at the usual rate for other property of that description. Thus the proprietors finally acknowledged the right of the assembly to tax their estates.

The success of Franklin’s first foreign mission was substantial. During this sojourn of five years in England he had made many valuable friends outside of court and political circles, including David Hume and Adam Smith. In 1759, for his literary and more particularly his scientific attainments, he received the Freedom of the City

of Edinburgh and the degree of Doctor of Laws from the University of St Andrews. (He had already received a Master of Arts at Harvard and at Yale in 1753, and at the College of William and Mary in 1756. And in 1762 he received the degree of Doctor of Civil Law at Oxford University.)

Franklin sailed for America in August 1762, hoping to be able to settle down quietly and devote the remainder of his life to experiments in physics. This quiet was interrupted, however, by the Paxton Massacre (14-Dec-1763) — the slaughter of 20 Indian children, women and old men at Lancaster, Pennsylvania, by some young rowdies from the town of Paxton, who then marched to Philadelphia to kill a few Christian Indians there. Franklin appealed to by the governor and raised a troop sufficient to frighten away the Paxton boys.

For the moment there seemed a possibility of an understanding between Franklin and the Pennsylvania proprietors.

Second diplomatic mission to England

But the question of taxing the estates of the proprietors came up in a new form, and a petition from the Assembly was drawn by Franklin, requesting the king to resume the government

of Pennsylvania. In the autumn election of 1764, the influence of the proprietors was exerted against Franklin, and by an adverse majority of 25 votes (out of 4,000) he failed to be re-elected to the Assembly. So the new Assembly sent Franklin again to England as its special agent to take charge of another petition for a change of government — which came to nothing.

But matters of much greater consequence soon demanded Franklin’s attention.

Early in 1764 Lord Grenville had informed the London agents of the American colonies that he proposed to lay a portion of the burden left by the war with France upon the shoulders of the colonists by means of a stamp duty, unless some other tax equally productive and less inconvenient were proposed. The natural objection of the colonies, as voiced for example by the Pennsylvania Assembly, was that it was a cruel thing to tax colonies already taxed beyond their strength, surrounded by enemies and exposed to constant expenditures for defense, and that it was an indignity that they should be taxed by a Parliament in which they were not represented. At the same time the Assembly recognized it as their duty to grant aid to the crown, according to their abilities, whenever required of them in the usual manner.

To prevent the introduction of the Stamp Act, which he characterized as the mother of mischief,

Franklin used every effort, but the bill was easily passed. It was thought that the colonists would soon be reconciled to it. Because he, too, thought so, and because he recommended John Hughes, a merchant of Philadelphia, for the office of distributor of stamps, Franklin himself was denounced — he was even accused of having planned the Stamp Act — and his family in Philadelphia was in danger of mob violence.

Franklin was questioned by Parliament as to the effects of the Stamp Act in February 1766. Edmund Burke said that the scene reminded him of a master examined by a parcel of schoolboys, and George Whitefield said: Dr Franklin has gained immortal honor by his behavior at the bar of the House. His answer was always found equal to the questioner. He stood unappalled, gave pleasure to his friends and did honor to his country.

Franklin compared the position of the colonies to that of Scotland in the days before the union, and in the same year (1766) audaciously urged a similar union with the colonies before it was too late. The knowledge of colonial affairs gained from Franklin’s testimony, probably more than all other causes combined, determined the immediate repeal of the Stamp Act. For Franklin this was a great triumph, and the news of it filled the colonists with delight and restored him to their confidence and affection.

However, another bill — the Declaratory Act — was almost immediately passed by the King’s party, asserting absolute supremacy of parliament over the colonies. In the succeeding Parliament, the Townshend Acts of 1767 imposed duties on paper, paints, and glass imported by the colonists; in addition, a tax was imposed on tea. The imposition of these taxes was bitterly resented in the colonies, where it quickly crystallized public opinion round the principle of No taxation without representation.

Despite the opposition in the colonies to the Declaratory Act, the Townshend Acts and the tea tax, Franklin continued to assure the British ministry and the British public of the loyalty of the colonists. He tried to find some middle ground of reconciliation, and kept up his quiet work of informing England as to the opinions and conditions of the colonies, and of moderating the attitude of the colonies toward the home government. He was accused in America of being too much an Englishman, and in England of being too much an American.

He was agent now, not only of Pennsylvania, but also of New Jersey, Georgia, and Massachusetts as well. The Earl of Hillsborough, who became Secretary of State for the Colonies in 1768, refused to recognize Franklin as agent of Massachusetts, because the governor of Massachusetts had not approved the appointment, which was by resolution of the Assembly. Franklin contended that the governor, as a mere agent of the king, could have nothing to do with the assembly’s appointment of its agent to the King; that the King, and not the King, Lords, and Commons collectively, is their sovereign; and that the King, with their respective Parliaments, is their only legislator.

Franklin’s influence helped to oust Hillsborough. Lord Dartmouth, whose name Franklin suggested, was made secretary in 1772 — and he promptly recognized Franklin as the agent of Massachusetts.

In 1773 there appeared in the Public Advertiser one of Franklin’s cleverest hoaxes, An Edict of the King of Prussia,

proclaiming that the island of Britain was a colony of Prussia, having been settled by Angles and Saxons, having been protected by Prussia, having been defended by Prussia against France in the war just past, and never having been definitely freed from Prussia’s rule; and that, therefore, Great Britain should now submit to certain taxes laid by Prussia — the taxes being identical with those laid upon the American colonies by Great Britain.

In the same year occurred the famous episode of the Hutchinson Letters. These were written by Thomas Hutchinson, Governor of Massachusetts, Andrew Oliver (1706-1774), his lieutenant-governor, and others to William Whately, a member of Parliament and private secretary to Prime Minister George Grenville, suggesting an increase of the power of the governor at the expense of the Assembly, an abridgement of what are called English liberties,

and other measures more extreme than those undertaken by the government. The correspondence was shown to Franklin by a mysterious member of parliament

to back up the contention that the quartering of troops in Boston was suggested, not by the British ministry, but by Americans and Bostonians. Upon his promise not to publish the letters Franklin received permission to send them to Massachusetts, where they were much passed about and were printed, and they were soon republished in English newspapers.

Upon receiving the letters, the Massachusetts Assembly resolved to petition the crown for the removal of both Hutchinson and Oliver. The petition was refused and was condemned as scandalous, and Franklin, who took upon himself the responsibility for the publication of the letters, in the hearing before the privy council at the Cockpit on 29 January 1774, was insulted and was called a thief by Alexander Wedderburn (the solicitor-general, who appeared for Hutchinson and Oliver), and was removed from his position as head of the post office in the American colonies.

Convinced that his usefulness in England was at an end, Franklin entrusted his agencies to the care of Arthur Lee. On the 21 March 1775 he set sail for Philadelphia.

During the last years of his stay in England there had been repeated attempts to win him to the British service, and in these same years he had done great work for the colonies by gaining friends for them among the opposition, and by impressing France with his ability and the excellence of his case.

Member of the Continental Congress

Upon reaching America, he heard of the fighting at Lexington and Concord, and with the news of an actual outbreak of hostilities his feeling toward England seems to have changed completely. He was no longer a peacemaker, but an ardent warmaker. On 6 May, the day after his arrival in Philadelphia, he was elected by the Pennsylvania Assembly a delegate to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia. In October he was elected a member of the Pennsylvania Assembly — but since members of that body were still required to take an oath of allegiance to the crown, he refused to serve. In Congress he served on as many as ten committees, and upon the organization of a continental postal system, he was made Postmaster General, a position he held for one year. (In 1776 he was succeeded by his son-in-law, Richard Bache, who had been his deputy.)

Along with Benjamin Harrison, John Dickinson, Thomas Johnson, and John Jay he was appointed in November 1775 to a committee to carry on a secret correspondence with the friends of America in Great Britain, Ireland and other parts of the world.

He planned an appeal to King Louis XVI of France for aid, and wrote the instructions of Silas Deane who was to convey it. In April 1776 he went to Montreal with Charles Carroll, Samuel Chase, and John Carroll, as a member of the commission which conferred with General Benedict Arnold, and attempted — without success — to gain the cooperation of Canada.

Immediately after his return from Montreal he was a member of the Committee of Five

appointed to draw up the Declaration of Independence, but he took no actual part himself in drafting that instrument, aside from suggesting the change or insertion of a few words in Jefferson’s draft. From 16 July 28 September he acted as president of the Constitutional Convention of Pennsylvania.

Along with John Adams and Edward Rutledge, Franklin was selected by Congress to discuss the terms of peace proposed by Admiral Richard Howe (Sep-1776 at Staten Island) , who had arrived in New York harbor in July — and who had been an intimate friend of Franklin. But their discussion was fruitless, as the American commissioners refused to retreat back of this step of independency.

Commissioner to France

On 26 September in the same year, Franklin was chosen as Commissioner to France to join Arthur Lee, who was in London, and Silas Deane (who had arrived in France in June 1776). He collected all the money he could command, between £3000 and £4000, lent it to Congress before he set sail, and arrived at Paris on the 22 December. He found quarters at Passy, then a suburb of Paris, in a house belonging to Le Ray de Chaumont, an active friend of the American cause who had influential relations with the Court, through whom he was enabled to be in the fullest communication with the French government without compromising it in the eyes of Great Britain.

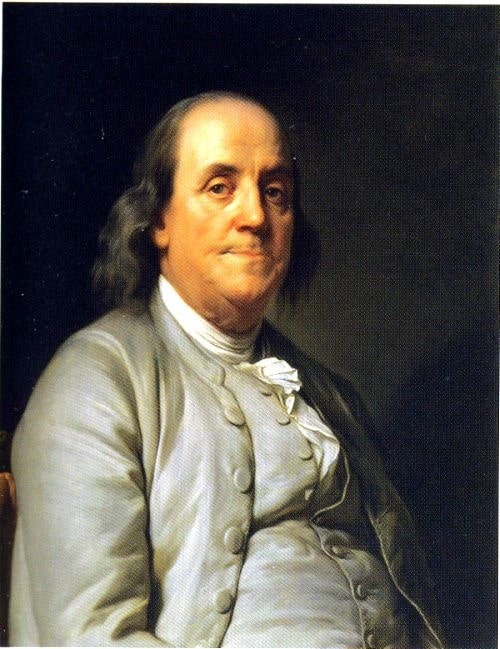

At the time of Franklin’s arrival in Paris he was already famous for his experiments in electricity. He was a member of every important learned society in Europe; he was a member, and one of the managers, of the Royal Society; and was one of eight foreign members of the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris. Three editions of his scientific works had already appeared in Paris, and a new edition had recently appeared in London. To all these advantages he added a political purpose — the dismemberment of the British empire — which was entirely congenial to every citizen of France. Franklin’s reputation,

wrote John Adams with characteristic extravagance,

…was more universal than that of Leibnitz or Newton, Frederick [the Great] or Voltaire; and his character more esteemed and beloved than all of them…. If a collection could be made of all the gazettes of Europe, for the latter half of the 18th century, a greater number of panegyrical paragraphs uponle grand Franklin would appear, it is believed, than upon any other man that ever lived.

According to Friedrich Christoph Schlosser,

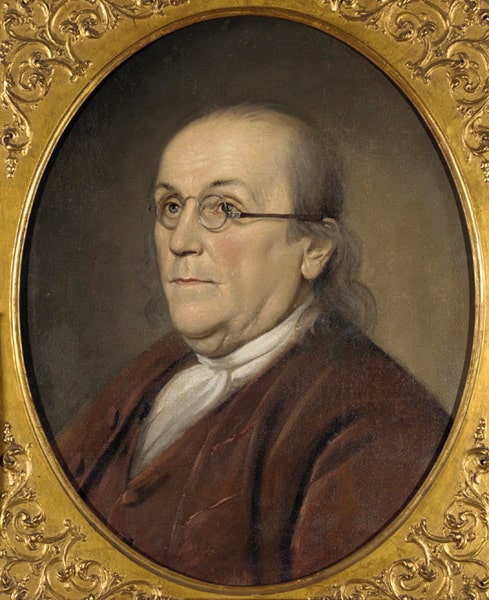

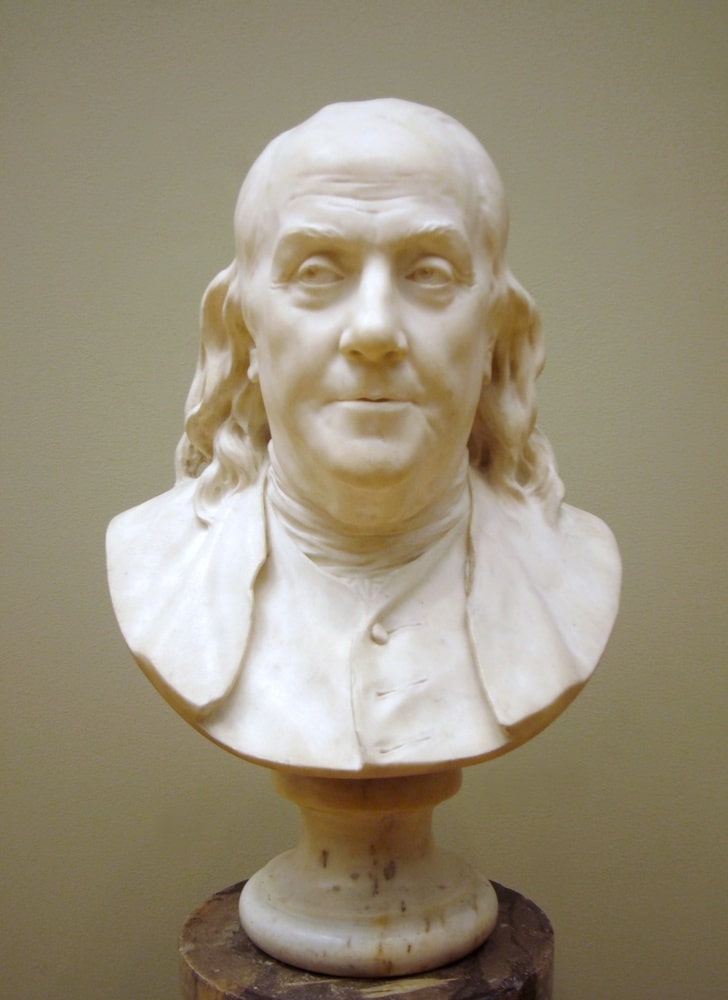

Franklin’s appearance in the French salons, even before he began to negotiate, was an event of great importance to the whole of Europe…. His dress, the simplicity of his external appearance, the friendly meekness of the old man, and the apparent humility of the Quaker, procured for Freedom a mass of votaries among the coon circles who used to be alarmed at its coarseness and unsophisticated truths. Such was the number of portraits, busts and medallions of him in circulation before he left Paris that he would have been recognized from them by any adult citizen in any part of the civilized world.

Franklin’s position in France was a difficult one from the start, because of the delicacy of the task of getting French aid at a time when France was unready to openly take sides against Great Britain. But on 6 February 1778, after the news of the defeat and surrender of Burgoyne had reached Europe, a Treaty of Alliance and a separate Treaty of Amity and Commerce between France and the United States were signed at Paris by Franklin, Deane, and Lee.

Plenipotentiary to France

On 28 October the U.S. Commission was discharged and Franklin was appointed sole Plenipotentiary to the French Court. Lee, from the beginning of the mission to Paris, seems to have had a mania of jealousy toward Franklin, or of misunderstanding his acts, and he tried to undermine his influence with the Continental Congress. John Adams, when he succeeded Deane (recalled from Paris through Lee’s machinations) joined in the chorus of fault-finding against Franklin. He dilated upon his social habits, his personal slothfulness, and his complete lack of a business-like system. But Adams soon came to see that — although careless of details — Franklin was doing what no other man could have done, and he ceased his harsher criticism.

Even greater than his diplomatic difficulties were Franklin’s financial straits. Drafts were being drawn on him by all the American agents in Europe and by the Continental Congress at home. Acting as American naval agent for the many successful privateers who harried the English Channel, and for whom he skillfully got every bit of assistance possible from the French government, open and covert, he was continually called upon for funds in these ventures.

Of the vessels to be sent to Paris with American cargoes which were to be sold for the liquidation of French loans to the colonies made through Pierre Beaumarchais, few arrived. Those that did come did not cover Beaumarchais’ advances, and hardly a vessel came from America without word of fresh drafts on Franklin. After bold and repeated overtures for an exchange of prisoners — an important matter, both because the American frigates had no place in which to stow away their prisoners, and because of the maltreatment of American captives in such prisons as Dartmoor — exchanges began at the end of March 1779, although there were annoying delays, and immediately after November 1781 there was a long break in the agreement; and the Americans discharged from English prisons were constantly in need of money.

In addition, Franklin was constantly called upon to meet the indebtedness of Lee and Ralph Izard and John Jay (who was in Madrid at the request of the American Congress). In spite of the poor credit of the struggling colonies, and of the fact that France was almost bankrupt — and in the later years was at war — and although Necker strenuously resisted the making of any loans to the colonies, France, largely because of Franklin’s appeals, expended, by loan or gift to the colonies, or in sustenance of French arms in America, a sum estimated at 60 million dollars.

Peace treaty with Great Britain

In 1781 Franklin, along with John Adams, John Jay, Thomas Jefferson, and Henry Laurens (then a prisoner in England) was appointed to a commission to make peace with Great Britain. In the spring of 1782 Franklin had been informally negotiating with Lord Shelburne, Secretary of State for the Home Department — through the medium of Richard Oswald, a Scotch merchant — and had suggested that England should cede Canada to the United States in return for the recognition of loyalist claims by the states. When the formal negotiations began Franklin held closely to the instructions of Congress to its commissioners, that they should maintain confidential relations with the French ministers and that they were to undertake nothing in the negotiations for peace or truce without their knowledge and concurrence,

and were ultimately to be governed by their advice and opinion.

Jay and Adams disagreed with him on this point, believing that France intended to curtail the territorial aspirations of the Americans for her own benefit and for that of her ally, Spain.

When at last the British government authorized its agents to treat with the commissioners as representatives of an independent power (thus recognizing American independence before the treaty was made), Franklin acquiesced to the policy of Jay. The preliminary treaty was signed by the commissioners on the 30 November 1782; it recognized American independence and granted it significant western territory. The final Treaty of Paris was signed in Paris on 3 September 1783.

By now Franklin had been in Paris for eight years. He repeatedly petitioned Congress for his recall, but his letters were unanswered, or his appeals refused — until 7 March 1785. Three days later, Jefferson, who had joined Franklin in August the year before, was appointed to his place. Asked if he had replaced Franklin, Jefferson replied, No one can replace him, sir; I am only his successor.

Final years

Franklin at last arrived in Philadelphia on 13 September, disembarking on the same wharf as when he had first entered the city.

He was immediately elected a member of the Municipal Council of Philadelphia, becoming its chairman; and he was chosen president of the Supreme Executive Council (the chief executive officer) of Pennsylvania. He was re-elected the following two years, serving from October 1785 to October 1788.

In May 1787 he became a delegate to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia (25-May —17-Sep). After a long, hot summer of disagreement and compromise in the Philadelphia State House, with more politicking after-hours, he used his influence to help secure the adoption of the U.S. Constitution.

As president of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, Franklin signed a petition to Congress (12-Feb-1790) for the immediate abolition of slavery. Six weeks later in his most brilliant manner, he parodied the attack on the petition made by James Jackson (1757—1806) of Georgia, taking Jackson’s quotations of Scripture with pretended texts from the Koran cited by a member of the Divan of Algiers in opposition to a petition asking for the prohibition of holding Christians in slavery. These were his last public acts.

Franklin’s last days were marked by a fine serenity and calm. He died in his house in Philadelphia in 1790, age 84, the immediate cause being an abscess in the lungs. He was buried with his wife in the cemetery at Christ Church.

Personal life

Physically Franklin was large, about 5 feet 10 inches tall, with a well-rounded, powerful figure. He inherited an excellent constitution from his parents (I never knew either my father or mother to have any sickness but that of which they dy’d, he at 89, and she at 85 years of age

) — but injured it somewhat by excesses. In early life he had severe attacks of pleurisy, from one of which, in 1727, he was not expected to recover; in later years he was the victim of stone and gout. When he was 16 he became a vegetarian for a time — to save money for books — and he always preached moderation in eating — though he was less consistent particular practice than as regards moderate drinking. He was fond of swimming and was a great believer in fresh air, taking a cold air bath regularly in the morning, when he sat naked in his bedroom beguiling himself with a book or with writing for half-an-hour or more. He insisted that fresh, cold air was not the cause of colds, and preached zealously the gospel of ventilation.

He was a charming talker, who used humor and a quiet sarcasm, along with a telling use of anecdote for argument.

In 1730 he married Deborah Read, in whose father’s house he had lived when he had first come to Philadelphia, to whom he had been engaged before his first departure from Philadelphia for London, and who in his absence had married John Rogers, a notorious debtor who soon fled to Barbados to avoid possible incarceration. The marriage with Franklin is presumed to have been a common-law marriage, for there is no proof that Read’s former husband was dead, nor that, as was suspected, a former wife was still alive when Rogers married Read, thus making the marriage void. His Debby,

or his dear child,

as Franklin usually addressed Read in his letters, received into the family — soon after her marriage — Franklin’s illegitimate son, William Franklin (1729—1813), with whom she afterwards quarreled. (Many speculate that William’s mother was Barbara, a servant in the Franklin household.)

Deborah, who was as much dispos’d to industry and frugality as

her husband, was illiterate and shared none of her husband’s tastes for literature and science. Her dread of an ocean voyage kept her in Philadelphia during Franklin’s two missions to England, and she died in 1774, while Franklin was in London. She bore him two children, one a son, Francis Folger, whom I have seldom since seen equal’d in everything, and whom to this day [thirty-six years after the child’s death] I cannot think of without a sigh,

who died when four years old of small-pox (1736); the other was Sarah (1744—1808), who married Richard Bache (1737—1811), Franklin’s successor as postmaster-general.

Franklin’s gallant relations with women after his wife’s death were probably innocent enough. Best known of his Frenchamie were Mme Helvétius, widow of the philosopher, and the young Mme Brillon, who corrected her Papa’s

French and tried to bring him safely into the Roman Catholic Church. With him in France were his grandsons, William Temple Franklin (William Franklin’s natural son), who acted as private secretary to his grandfather, and Benjamin Franklin Bache (1769-1798), Sarah’s son, whom he sent to Geneva to be educated, and who later became editor of the Aurora, one of the leading journals in the Republican attacks on Washington.

Franklin early rebelled against New England Puritanism and spent his Sundays in study and reading instead of attending church. His free-thinking ran its extreme course at the time of his publication in London of A Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity, Pleasure and Pain (1725), which he recognized as one of the great errata of his life. He later called himself a deist or theist, not discriminating between the terms. To his favorite sister he wrote: There are some things in your New England doctrine and worship which I do not agree with; but I do not therefore condemn them, or desire to shake your belief or practice of them.

Such was his general attitude.

He did not believe in the divinity of Jesus, but thought his system of morals and his religion, as he left them to us, the best the world ever saw, or is like to see.

His intense practical-mindedness drew him away from religion, but drove him to a morality of his own — the art of virtue,

he called it — based on thirteen virtues each accompanied by a short precept. (The virtues were Temperance, Silence, Order, Resolution, Frugality, Industry, Sincerity, Justice, Moderation, Cleanliness, Tranquility, Chastity and Humility, the precept accompanying the last-named virtue being Imitate Jesus and Socrates.

)

He made a business-like little notebook, ruled off spaces for the thirteen virtues and the seven days of the week, determined to give a week’s strict attention to each of the virtues successively … [going] thro’ a course compleate in thirteen weeks and four courses in a year,

marking for each day a record of his adherence to each of the precepts. And conceiving God to be the fountain of wisdom,

he thought it right and necessary to solicit His assistance for obtaining it,

and drew up the following prayer for daily use:

O powerful Goodness! bountiful Father! merciful Guide! Increase in me that wisdom which discovers my truest interest. Strengthen my resolution to perform what that wisdom dictates. Accept my kind offices to Thy other children, as the only return in my power for Thy continual favours to me.

He was by no means prone to overmuch introspection, his great interest in the conduct of others being shown in the wise maxims of Poor Richard, which were possibly too utilitarian but were wonderfully successful in instructing American morals. His Art of Virtue, on which he worked for years, was never completed or published in any form.

Benjamin Franklin, Printer

Benjamin Franklin, Printer,

was Franklin’s own favorite description of himself. He was an excellent compositor and pressman; his workmanship, clear impressions, black ink and comparative freedom from errata did much to get him the public printing in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, as well as the printing of the paper money and other public matters in Delaware. The first book with his imprint is The Psalms of David Imitated in the Language of the New Testament and apply’d to the Christian State and Worship. By I. Watts …, Philadelphia: Printed by B. F. and H. M. for Thomas Godfrey, and Sold at his Shop, 1729. The first novel printed in America was Franklin’s reprint in 1744 of Henry Fielding’s Pamela; the first American translation from the classics which was printed in America was a version by James Logan (1674—1751) of Cato’s Moral Distichs (1735). In 1744 he published another translation of Logan’s On Old Age, by Cicero, which Franklin thought typographically the finest book he had ever printed.

In 1733 he had established a press in Charleston, South Carolina, and soon after did the same in Lancaster, Pennsylvania; in New Haven, Connecticut; in New York; in Antigua; in Kingston, Jamaica, and in other places.

After 1748, Franklin had little connection with the Philadelphia printing — when David Hall became his partner and took charge of it. But in 1753 he was eagerly engaged in having several of his improvements incorporated in a new press, and more than twenty years after was actively interested in John Walter’s scheme of logography. In France he had a private press in his house in Passy, on which he printed what he called bagatelles. Franklin’s work as a publisher is for the most part closely connected with his work in issuing the, Gazette and, making him a rich man, Poor Richard’s Almanack.

The autobiography and other writings

Bejamin Franklin’s Autiobiography ranks among the few great autobiographies ever written. In its simplicity, facility, and clearness, his style owed something to Daniel De Foe, something to Cotton Mather, something to Plutarch, more to Bunyan, as well as to his own early attempts to reproduce the manner of the third volume of the Spectator — and not the least to his own careful study of word usage.

From Xenophon’s Memorabilia, which he learned when a boy, Franklin learned the Socratic method of argument. He resembled Jonathan Swift in the occasional broadness of his humor, in his brilliantly successful use of sarcasm and irony, and in his mastery of the hoax. Balzac said of him that he invented the lightning-rod, the hoax (le canard) and the republic.

Among his more famous hoaxes were the Edict of the King of Prussia (1773 — described above); the fictitious supplement to the Boston Chronicle, printed on his private press at Passy, France (1782), and containing a letter with an invoice of eight packs of 954 cured, dried, hooped and painted scalps of rebels, men, women and children, taken by Indians in the British employ

; and another fictitious Letter from the Count de Schaumberg to the Baron Hohendorf commanding the Hessian Troops in America (1777) — the Count’s only anxiety is that not enough men will be killed to bring him in moneys he needs, and he urges his officer in command in America to prolong the war … for I have made arrangements for a grand Italian opera, and I do not wish to be obliged to give it up.

Closely related to Franklin’s political pamphlets are his writings on economics, which, though undertaken with a political or practical purpose, rank him as the first American economist. He wrote A Modest Enquiry into the Nature and Necessity of a Paper Currency (1729), which argued that a plentiful currency will make rates of interest low and will promote immigration and home manufactures — which did much to secure the further issue of paper money in Pennsylvania.

After the British Act of 1750 forbidding the erection or the operating of iron or steel mills in the colonies, Franklin wrote Observations concerning the Increase of Mankind and the Peopling of Countrie (1751). Its thesis was that manufactures come to be common only with a high degree of social development and with great density of population, and that Great Britain need not, therefore, fear the industrial competition of the colonies. But it is better known for the estimate (adopted by Adam Smith) that the population of the colonies would double every quarter-century; and for the likeness to Malthus’s preventive check

of its statement: The greater the common fashionable expense of any rank of people the more cautious they are of marriage.

His Positions to be examined concerning National Wealth (1769) shows that he was greatly influenced by the French physiocrats after his visit to France in 1767. And Wail of a Protected Manufacture, voices a protest against protection as raising the cost of living; and he held that free trade was based on a natural right.

He knew Lord Kames, David Hume, Adam Smith, and corresponded with the comte de Mirabeau (the friend of Man

). Some of Franklin’s more important economic theses are: that money as coin may have more than its bullion value; that natural interest is determined by the rent of land valued at the sum of money loaned; that high wages are not inconsistent with a large foreign trade; that the value of an article is determined by the amount of labor necessary to produce the food consumed in making the article; that manufactures are advantageous but agriculture only is truly productive; and, that when practicable, state revenue should be raised by direct tax.

The scientist and inventor

As a scientist and inventor, Franklin has been decried by experts as an amateur and a dabbler; but it should be remembered that it was always his hope to retire from public life and devote himself to science. Franklin wrote a paper on the causes of earthquakes for his Gazette (15-Dec-1737); and he eagerly collected material to uphold his theory that waterspouts and whirlwinds resulted from the same causes. In 1743, from the circumstance that an eclipse not visible in Philadelphia had been observed in Boston — because of a storm, where the storm, although north-easterly, did not occur until an hour after the eclipse — he surmised that storms move against the wind along the Atlantic coast.

In the year before (1742) he had planned the Pennsylvania fire-place,

— better known as the Franklin stove

— which saved fuel, heated the entire room, and had the same principle as the hot-air furnace. The stove was never patented by Franklin, but it was described in his pamphlet dated 1744. He was much engaged at the same time in remedying smoking chimneys, and as late as 1785 he wrote to Jan Ingenhousz — physician to the emperor of Austria — on chimneys and draughts. He also remedied smoking street lamps by a simple contrivance.

In 1746, Franklin took up the study of electricity when he first saw a Leyden jar, which he then improved by using granulated lead in the place of water for the interior armatures. He recognized that condensation is due to the dielectric and not to the metal coatings. A note in his diary (7-Nov-1749) shows that he then conjectured that thunder and lightning were electrical manifestations. In the same year, he planned the lightning-rod — long known as Franklin’s rod

— which he described and recommended to the public in 1753, when the Copley medal of the Royal Society was awarded to him for his discoveries.

In 1752, Franklin performed the famous experiment with a kite that proved lightning was an electrical phenomenon. He overthrew entirely the friction

theory of electricity and conceived the idea of plus and minus charges (1753), though he mistakenly thought that the was sea the source of electricity.

Franklin wrote to David Rittenhouse in June 1784 that the sum of his own conjectures was that Newton’s corpuscular theory light was wrong, and that light was due to the vibration of an elastic ether.

In navigation he suggested many new contrivances, such as water-tight compartments, floating anchors to lay a ship to in a storm, and dishes that would not upset during a gale. He studied with some care the temperature of the Gulf Stream; beginning in 1757 made repeated experiments with oil on stormy waters.

As a mathematician he devised various elaborate magic squares and novel magic circles, of which he speaks apologetically, because they are of no practical use. Always much interested in agriculture, he made a special effort to promote the use of plaster of Paris as a fertilizer. He took a prominent part in aeronautic experiments during his stay in France. He made an excellent clock, which because of a slight improvement introduced by James Ferguson in 1757, was long known as Ferguson’s clock. In medicine, Franklin was considered important enough to be elected to the Royal Medical Society of Paris in 1777, and became an honorary member of the Medical Society of London in 1787. In 1784, he was on the committee which investigated Mesmer, and the report is a document of lasting scientific value. Franklin’s advocacy of vegetarianism, of a spare and simple diet, and of temperance in the use of liquors, and of proper ventilation has already been mentioned. His most direct contribution to medicine was the invention, for his own use, of bifocal eyeglasses.

Summary

A summary of so versatile a genius is impossible. With his services to America in England and France, he ranks as one of the heroes of the American Revolution and as the greatest of American diplomats. Almost the only American scientist of his day, he displayed remarkably deep as well as remarkably varied abilities in science and deserved the honors enthusiastically given him by the savants of Europe.