Contents

Contents

Leon G. Campbell received his Ph.D. from the University of Florida in 1970. An authority on Spanish American and California history, he is the author of several works, including The Military and Society in Colonial Peru, 1750-1810, American Philosophical Society Press, Philadelphia, PA, 1978.

This essay was written while he was a Professor of History at the University of California, Riverside. He has since moved to Northern California.

Observation of the North American Revolution offers historians and others the opportunity to retell the dramatic story of Anglo-American cultural development. From beachheads at Jamestown and Plymouth and Boston, pioneers valiantly established colonies and secured independence. Then began their march westward across the Appalachian barrier, over the interior valley, and through the Great Plains. Ultimately, they planted settlements in the valleys of California and Oregon, during the nineteenth century, fulfilling a destiny which had been manifest years earlier.

The entire “frontier hypothesis,” announced in 1893 by historian Frederick Jackson Turner, pictured a population stream flowing east to west across the continent, English in character, dynamic in spirit.1 But while Turner correctly identified this as the main artery of our national civilization, his research implied a continent devoid of other civilizations. Neglected were the subsidiary streams which have contributed fundamentally to the American character: French Canadians moving south in the seventeenth century into Michigan, Illinois, and throughout the Great Plains; Spaniards from the Caribbean Islands of Cuba and Hispaniola traversing Florida into Carolina and Virginia, in the sixteenth century, and others radiating north from Mexico throughout an area from Louisiana to California in the eighteenth century, continuing unbroken a process of conquest which had been begun in the Caribbean two centuries earlier.

By the nineteenth century the Spanish empire in America was of awesome size, stretching unbroken from the Cape Horn to San Francisco. As Robin A. Humphreys has observed, “the distance from Stockholm to Cape Town is less extensive. Within the area ruled by Spain in America,” he noted, “all western Europe from Madrid to Moscow might lie and be lost.”2 The virtue of Spanish America as a field for historical inquiry in the United States was recognized and explored, thanks in large part to the efforts of Herbert Eugene Bolton, who evolved the concept of the Americas, North and South, as a single geographic unit, and urged that the United States be recognized not as simply an outpost of England, but rather a complex region understandable only in terms of the Anglo-French and Anglo- Spanish intrusions that had altered its culture and behavioral patterns.3

Despite the efforts of Bolton and his students, all were not convinced of the importance of studying remote borderlands regions such as Alta California, the furthest removed and smallest of Spanish provinces, which, within half a century of Spanish American independence, was absorbed by the relentless drive of the westward-moving Anglo-American pioneers. Zoeth S. Eldridge, for example, delivering the presidential address to the California Genealogical Society on July 13, 1901, admitted that the Spanish period of California history was an interesting chapter in the state’s development and that the Californios seemed to have been “a brave and generous, honest and kindly people.” Yet, because they did not possess “the restless energy and enterprise of the Americans,” he predicted they would soon disappear as a race and their cultural traditions would be lost.4 And Bernard De Voto, in The Year of Decision, 1846, concluded that “if one is to sympathize with the (old) Californians, it must be only a nostalgic sympathy, a respect for things past.” Implicit in his remarks was the feeling that Spanish and Mexican California was a small, culturally backward area, governed by a group which contributed little that was new or original to mankind, more destined to become the preserve of antiquarians than scholars.5

Because the Spanish archives were destroyed in the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, much speculation and considerable mythology has surrounded early California history. On one hand, Spanish California has been held up as an example of the fact that Spain failed to develop true settlement colonies in the United States, while the British succeeded in doing so. This inattention to Spanish colonial endeavor helps to propagate a Black Legend of Spanish corruption, bigotry, inhumanity, and inferiority, according to which the Spanish came to California as they had come earlier to Peru and Mexico, lusters after wealth and glory, content to explore and conquer but less willing and able to sow the seeds of permanency and progress.6 Equally misleading is the school of historiography which has attempted to rescue Spanish California from its detractors. Nellie Van Der Grift Sanchez’ Spanish Arcadia is a prime example of this genre of historical literature. Comparing Spanish California to the isolated mountain kingdom of Arcadia in Ancient Greece, Sanchez paints an idyllic picture of a quiet, simple, pastoral area, peopled with wealthy rancheros, many of them titled Spanish Dons, and saintly mission fathers.7 It is understandable why this myth was taken to heart by Californians of a later day.8 Many found it comforting to remember, during the rapidly modernizing twentieth century, a simpler agrarian society which lacked the impediments of imperfect modernization – urban sprawl, squalid slums, class struggle, and of course smog.

There are, however, at least three sounder reasons for re-examining Spanish California during the era of the North American revolution. First, other historical experiences offer us insights into our own past. Like their Anglo counterparts, Spanish pioneers moved north from Mexico across rugged, treacherous lands, and faced Indians who threatened the permanent occupation of these frontier regions. Both shared problems of converting and assimilating Indian nations; both faced conflicts between civil, military and ecclesiastical authorities over the control of conquered regions; and the societies which emerged on the Anglo and Spanish frontiers were both products of isolation and deprivation. Accordingly, they were as different from their metropolitan counterparts, perhaps more so, than they were from each other.

Second, Hispanic culture contributed fundamentally to the development of California society. We cannot be unaware, for example, of the plaza, grid systems in town planning, and Spanish architectural styles. At a more individual level, persons of Spanish heritage preserve an intense localismo, or respect for one’s own locale or district, a deep belief in personalismo, which glorifies the individual over an abstract principle, religious and familial practices, and an intense preoccupation with the present, not generally shared by their Anglo counterparts.

Finally, we should be aware, as Leonard Pitt has noted, that California history is largely a story of immigration and nativism, of cultural confrontation, and of the submergence of California’s alien cultures into the American melting pot.9 The very unfamiliarity of westward-moving Anglos in the mid-nineteenth century with Hispanic culture and society led to conflicts and open warfare in Texas and elsewhere. Throughout the southwest, the defeat of relatively static, traditionalist societies by those more oriented to technology and the ideal of progress, produced cultural shock waves of seismic intensity. Ironically, the dominant Yankees arriving in 1848 were for once cast in the role of immigrants, while the native-born Californios were reduced to the status of foreigners, veritable strangers in their native land. The relegation of Spanish and Mexican Americans to minority status in areas where they once constituted overwhelming majorities has its origins in the late Hispanic period and continues to remain the most important problem resulting from the cultural intersection of 1848.

I should like to concern myself here with the nature of presidial society in Spanish California during the revolutionary era, and more specifically with the common soldiers and their officers, who, for nearly a century, stood watch over this remote outpost of empire. Considerable attention has already been paid to the missions and mission fathers, men of no small amount of talent and influence. Some has also been given to the intrepid explorers of California, such as Juan Bautista de Anza and Gaspar de Portola, yet little attention has been given to the presidial institution, which historian Charles E. Chapman has called “the backbone of the province of California.” Nor has any composite picture been drawn of the soldiery, which the same author refers to as “a sine qua non, or absolute essential, of the system.”10

Lest it smack of the antiquarianism against which De Voto and others have warned, let me justify this restriction of field. First, there exists a considerable body of primary materials on these men in the archives of Spain and the Bancroft Library. These data allow us to reconstruct, to use historian James Lockhart’s words, the history of a society, to deal with “the informal, the unarticulated, the daily and ordinary manifestations of human existence, as a vital plasma in which all more formal and visible expressions are generated.”11 Second, the fact that the presidial soldiery was a small, well-defined group of about 200 men, makes it possible to examine this body rigorously and form a collective social profile of the soldiers. Since immigration to California was almost completely ended by the Yuma Massacre of 1781, which closed the land route from Sonora, marriage patterns were endogamous and family groups remained largely intact. Third, and most important, the particular situation of California meant that the soldiers functioned not primarily as fighters, but rather as administrators, artisans, and rancheros, a complex of activities which may have been typical of the larger society of which they formed a part. Hence, the pattern of activities emerging at the presidial level seems to shed considerable light on society and economics at the provincial level, and points up peculiarities of both which manifest themselves to this day.

Alta California was settled for defensive purposes rather than out of any belief in the profitability of the area. Following the French and Indian War in 1763, Englishmen were free to move westward and involve themselves in the lucrative fur trade of the Pacific Northwest which had for so long been in French hands. This created a potential challenge to Spanish claims. And, thanks largely to the efforts of Jose de Galvez, the dynamic Visitor-General of New Spain (Mexico), a process of defensive modernization was begun in the northern provinces, which were consolidated and placed under separate command. Playing upon his sovereign’s fear of an English, Dutch, or Russian attack upon the rich silver mining districts of northern Mexico, which constituted the lifeblood of empire, Galvez obtained permission from Charles III to occupy the ports of San Diego and Monterey, projects which had long been considered and periodically given up as hopeless.

In 1769 Galvez assembled the so-called “sacred expedition,” a handful of Spanish soldiers and a group of Franciscan missionaries, who together made an overland and seaborne journey to the area north of Baja. Logistically, the group faced tremendous difficulties, but equally as serious a threat to the success of the venture was the animosity existing between the military and religious members of the expedition. This was a long-standing problem. Galvez and the Crown, distrusting the independence of the Jesuit fathers who had earlier colonized the Baja Peninsula, had turned the missionary duties in Alta California over to the grey-robed Order of Friars Minor. Unlike the Jesuits, the Franciscans were not given full control over military and civil matters, but were limited to the control of religious affairs only. Alta California was to be placed under military governorship. The missionaries and military, then, had quite different ideas about what they were doing and why, assuring that the process of colonization would be punctuated with disputes.12

In 1774, the same year that Bostonians resisted the Intolerable Acts of the English government, Spanish authorities in Mexico dispatched Captain Juan Bautista de Anza (left) from the Tubac presidio south of Tucson to blaze a trail overland to Alta California. De Anza reached Monterey in the spring of 1774. The following year, on his second expedition, he pushed further north to the Bay of San Francisco; and, shortly after the Americans penned their Declaration of Independence, the mission and presidio of San Francisco were founded, on September 17, 1776. With this established, the Crown decreed the following year that the capital of the Californias should be transferred from Loreto, in Baja, to Monterey.13

With the founding of the presidio of Santa Barbara in 1782, the province of California was divided into four presidio districts. The presidio, or fort, was Spain’s defensive arm of colonization. Throughout the southwest the sword moved in tandem with the cross, with missions and presidios being established next to one another, the latter affording the former the protection it required to enable it to Christianize and acculturate the Indians. The presidial district of San Francisco extended from the northern frontier about as far north as Santa Rosa, to the Pajaro River to the south; the Monterey presidial district stretched between the Pajaro and Santa Maria Rivers, while that of Santa Barbara covered the region from the Santa Maria River to and including the Mission San Fernando. That of San Diego comprised the region between San Fernando and the Tia Juana River to the south. The 1781 Regulation, which was established for the government of Alta California, provided for a 202-man presidial force to be divided among the four districts. The primary responsibilities of the soldiers were to defend the 600-mile coastline and the missions within their districts. To this end, small detachments of soldiers were established in each mission and civil pueblo.14

Although the missions, due to the presence of Indian neophytes who worked the lands and the agricultural expertise of the fathers, became generally self-supporting within a matter of years, the problems of feeding the presidios remained critical. Because supply lines from San Blas were difficult to maintain and the mission fathers protested against requisitions on their crops and herds to feed the garrisons, it was decided to establish two civil towns in the northern and southern regions of the province. These were to be populated by settlers drawn from northern Mexico who were to develop the agricultural resources of these areas. In 1777, Governor Felipe de Neve collected men from the presidios of Monterey and San Francisco and in that year established the town of San Jose de Guadalupe southeast of the Mission of Santa Clara de Asis which had been founded the previous year. In 1781 the pueblo de Nuestra Senora de la Reina de Los Angeles del Rio Porciuncula was founded to the south. Thereafter, only one other civil town, that of Branciforte, located in 1797 near the Mission Santa Cruz, was founded in Alta California.15

Surviving data on these earliest frontier settlements in Alta California indicate that the region was among the smallest outposts of Spanish America, populated by poor, unskilled, largely illiterate members of the lowest strata of Mexican society. Major South American cities such as Potosi in Upper Peru had populations in excess of 100,000 persons as early as 1575, unequalled by cities such as Philadelphia until 1830. Yet census figures show that as of 1781, the four presidios, two pueblos, and eleven missions of the province of Alta California were populated by no more than 600 persons exclusive of the indigenous groups. While this number grew to 3,700 just prior to independence in 1822, the closing of the Anza Trail in 1781 meant that this increase was due largely to the birth of descendents of the earlier colonists rather than to the arrival of new ones. By independence, then, most of the inhabitants were Californios, or natives of the province.

The presence since 1777 of the capital in Monterey caused this region to become the hub of social and political life in the province and by 1830 the city had a population of 950 persons, the largest urban area in the region. San Diego, with a population of 520 persons at independence, was the next-largest area, although slightly less favored agriculturally than Monterey because of the infertility of the soil. Santa Barbara, which had a population of 237 persons in 1790, grew rapidly in the last years of Spanish rule as the ranching economy developed, having a population of 850 persons in 1810 and rivalling Monterey in importance. San Francisco remained a small hamlet of 130 persons in 1787, maintained primarily to defend the northern perimeter of the province from a Russian or English attack.16

Census data taken in Alta California confirm the fact that the first Californios were largely non-whites, or mestizos, of mixed Spanish and Indian parentage, drawn from the presidial towns of northern Mexico or forcibly conscripted from the jails of the same regions to relieve overcrowded conditions. Men of wealth could not be expected to make the journey, not only because the hardships were many and the chances of material gain small, but also since the Spanish hidalgo, or gentleman, refused to idealize agricultural pursuits, preferring instead to enter the religious, military, or civil bureaucracies in more metropolitan areas where promotional opportunities were more assured. Nor did men of good family seek regular army careers which took them to the frontiers, but chose rather to receive militia commissions which allowed them to serve closer to home. Since persons of moderate and even poor circumstances also clung to these gentlemanly pretensions only the mixed-blood and the misbegotten ventured north from Mexico.

While some skilled workers accompanied the sacred expedition of 1769, as a group the entrepreneurial did not come to Alta California in large numbers. The original settlers of San Jose and San Francisco were, by their own admission, totally lacking in skills and drawn from the poorest elements of Sinaloa. In Los Angeles the same applied, with not one of the pobladores being able to sign their names to grants of land made to them in 1786. Only Jose Tiburcio Vasquez, out of nine heads of families in San Jose, could read or write. The same general situation held true in the presidial garrisons. Only fourteen of the fifty soldiers in Monterey were considered literate by their superiors, while only seven out of thirty in San Francisco were accorded this ability.17

Because the few literate and educated persons in the colony were the Franciscan friars, men of cultivated birth and a sense of purpose which the soldiers did not share, it was common for the soldiers and settlers to be depicted as a lazy and dissolute lot, good for nothing but drinking, gambling, and pursuing Indian women. Although the mission fathers grudgingly recognized the need for presidial protection, they resented having to share authority with the military governor in Monterey, whose conception of good government frequently diverged from their own. They also begrudged the governor’s land grants which permitted the soldiers to raise livestock on properties which the fathers purported to hold in trust for the Indians. They considered the mixed-blooded soldiers and their officers of little Christian virtue and hence a threat to their spiritual mission. Not infrequently, mission fathers refused to allow the soldiers to attend Mass or conversed among themselves in Latin to prevent their eavesdropping, adding to the tensions between the two groups.18

For their part, California governors and presidial commanders found the mission priests to be a haughty lot who sometimes considered themselves superior to the military. Commandants disliked being required to use their scarce resources to chase runaway Indian neophytes and resented the economic dependence of the presidios on the missions. Although requisitions made to the presidios by the missions were covered by situados or subsidies from the government in Mexico, these were frequently in arrears, causing the mission fathers to assert that they were forced to feed the soldiers gratuitously. During the early years of the colony, so deep did the conflict become between Father Junipero Serra and Governor Pedro Fages that Serra removed the Mission San Carlos Borromeo in Monterey to a site along the Carmel River farther removed from Fages’ jurisdiction. In response, Fages refused to affirm Serra’s requests to establish additional missions on the grounds that he lacked a sufficient number of soldiers to protect them.19

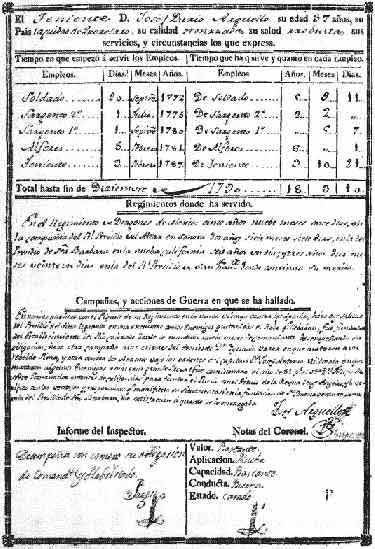

Unfortunately, the picture of the presidial soldiery which most often emerges is that usually given by the mission fathers with whom they were constantly at odds. While wrongdoing and mistreatment of the Indians were not exceptional among the presidials, other data give a more accurate picture of the California military during this period. Most of them were of low birth, born of presidial families along the northern Mexican frontier. For lack of alternatives they entered the presidial companies, being too poor to secure commissions or cadetships. Most had served as soIdados de cuera (left), or leather jacket soldiers in Northern Mexico, so-named for the several thicknesses of deerskin which they wore to protect themselves against Indian arrows. Theirs was dangerous and unrewarding work, especially in areas like California where promotions were likely to be slow and commissions difficult to obtain. As the grizzled Sergeant Pedro Amador wryly commented in his service record, the only compensation he had received for eighteen year’s service in California was fourteen Indian arrows in his body.20 Nor was California service well-regarded by Mexican authorities who most often chose to use the province as a dumping ground for reprobates and criminals. In 1773, for example, two soldiers were tried in Mexico for assaulting an Indian girl and her soldier companion in San Diego. After the case dragged on for five years, the men’s lives were spared on a technicality. As punishment, however, the court condemned them to spend the balance of their lives as citizens of California.21

Because the California Indians posed no continuing military threat as did the tribes of Texas and New Mexico, promotional considerations within the presidios after 1769 came to be based more upon a soldier’s literacy and administrative talents than his military capacity. The fragile nature of the presidial economy dictated that commandants and paymasters be men of unquestioned honesty, possessed of managerial and administrative skills. Since California was almost completely dependent upon supplies and subsidies from Mexico which arrived on a yearly basis, corrupt and/or inefficient management might incapacitate the defense of an entire region by making it impossible to pay and feed the soldiery or provide them with equipment.

Presidial records indicate that California governors after 1769 passed over soldiers of unquestioned bravery in favor of retaining men of administrative capacity on the payroll. Portola’s intrepid trailblazer, Lieutenant Jose Francisco de Ortega, for example, who enjoyed the powerful patronage of Father Serra, was considered unsuitable for command, and found others of lower rank promoted over him. Conversely, Hermengildo Sal, an ordinary soldier who had been forcibly conscripted into the ranks and sent to California as punishment for some undisclosed crime, apparently taught himself to read and write, a prerequisite for promotion above the rank of corporal. Showing a flair for management when placed in charge of the presidial warehouse in San Francisco, he was given the rank of sergeant in 1782 and sent to Santa Barbara. When the commandant there was dismissed for illegal activities two months after his arrival, he found himself commissioned as an ensign and placed in command of the fort. Sal later became commandant in San Francisco and was praised by Admiral George Vancouver as a man of considerable education and business acumen. In a similar fashion, presidial commands were bestowed upon Jose Dario Arguello and Felipe de Goycocoechea, both former enlisted men, as the result of their success in distributing public lands to the settlers of Los Angeles and in transferring the presidial treasuries during the general reorganization of 1781.22

A further key to the character of the presidial soldiery can be obtained through the marriage and baptismal certificates retained in the mission archives. Because enlistments were for ten-year periods, many soldiers chose to settle down and marry within the district. Fully two-thirds of the California soldiers were registered as married, while those remaining single were often living with Indian women whom they had taken as common-law wives. Observers have remarked that the soldiers were an optimistic lot who aspired to marry their commandants’ daughters or other women of equally elevated station.

Because there seems to have been an easy air of familiarity among the officers and men, this was not impossible by any means.23 Contemporary accounts indicate a lack of social distance within presidial society which, after all, was ethnically more homogenous than in Mexico, where the officer corps was white and well-born. A surviving case in which a commandant’s wife released a group of soldiers whom her husband had jailed, implies that a relaxed atmosphere pervaded the garrisons, one with strong familial overtones. Governors and commanders assumed that the soldiers would remain in California following their tours of duty and local marriages and land grants were strong inducements to this end. As historian Max Moorhead has found in a lifetime of studying the frontier soldiery, the presidial was neither a swashbuckler nor a carefree teenager, but a mature man, usually married and with children to support.24 We might simply conclude that the California presidial, through marriage and land holding, rapidly made the transition from soldier to settler within a short time of his arrival in California.

Because of the need to physically occupy unsettled regions and the constant requirement to make the colony agriculturally self-sufficient, presidial soldiers were granted lands and given a pension following an eighteen-year term of enlistment. This was an uncommon practice in other areas, where defensive considerations outweighed economic ones, since it was difficult to assemble soldiers living off the post and land was already closely held.25 Although a relatively small number of mercedes, or Royal grants of land, were made during the Hispanic period of California history, records indicate that former presidial soldiers were the primary recipients of these awards. For example, Juan Jose Dominguez, a scout for the Portola expedition, was granted a rancho of 74,000 acres for his services to the Crown, while Luis Peralta, a former presidial sergeant, was given control of lands which today encompass the cities of Berkeley, Alameda, and Oakland. Similarly, presidial commanders such as Ensign Jose Maria Verdugo held sixty-four square leagues (166 square miles) of land on which he ran 5,000 head of cattle, while Ensign Jose Francisco Ortega, the commandant in Santa Barbara, controlled the huge Refugio rancho nearby. An 1831 listing of the larger California ranchos indicates that most of the rancheros were ex-soldiers, controlling private grants up to 300,000 acres in size.26

Foreign affairs were of only minimal concern in this isolated settlement. Spain had already been at war with England six times since the beginning of the century and was to wage war against her three more times prior to 1822. Thus, the Royal Order of July 8, 1779, by which Governor Felipe de Neve was notified of the state of war between the two countries, hardly provoked a reaction in California. No declaration of war had ever brought troops to California nor was there a sufficient number of settlers to adequately defend the province from attack; hence, the Crown’s order to the Californios “to make war by land and sea” against the British made little sense. Letters between members of the California priesthood indicate that this group was aware of the war but make no mention of the fact that the North American colonies were in revolt against the mother country or that the Spanish Crown was in support of their actions. This was probably because officials in Madrid and Mexico provided provincial governors with no more information than was absolutely necessary. Whatever the case, provincial administrators would have made no mention of the fact, it being considered improper for local authorities to comment upon policy matters in their correspondence. Their business was to comply with Royal orders, not comment on them. Unofficially, however, one can gain some reaction about the war. Father Pablo Mugartegui referred to Governor Neve as a “malicious reprobate” in his letters to Serra, and questioned the ability of the presidials to defend the province in any event.27

While no direct connection can be established to link California more closely to the Revolution, other events tie the two together. In 1778 the English Captain James Cook had sailed to the Pacific on what was ostensibly a scientific expedition. While the Crown had ordered Cook not to interfere with the Spaniards, he was given secret instructions to reconnoiter areas of future colonial interest as part of a scheme which possibly sought to secure new colonial territories in the Pacific Northwest. With the outbreak of the North American Revolution the Mexican government was forced to suspend its costly explorations up the Pacific Coast in 1779, thus averting a confrontation with England in the Pacific which would likely have become entangled with other aspects of the revolution.

With the publication of Admiral Cook’s journal following the war, there was unleashed, to use the words of Warren Cook, a “flood tide of empire” throughout the Pacific Northwest. American and British merchants and explorers increasingly moved into the area to engage in the lucrative sea otter trade and the very profitability of this venture caused a renewal of European rivalry which had lain dormant since the days of Drake. In 1789 a Spanish expedition dispatched from Mexico to Nootka Sound, located on the western shore of Vancouver Island, found British, American, and Portuguese ships lying at harbor. Although the Spanish drove them off, when England threatened war Spain was forced to renounce its claims to the area and pull back its borders to San Francisco, primarily because it could secure no aid from the French, then embroiled in their own Revolution. In 1790, with the signing of the Nootka Treaty, Spain reversed a foreign policy which had been aggressively expansionist since the sixteenth century. In so doing, it caused California to become more exposed to the threat of attack.28

As the Pacific Northwest opened to foreigners after 1790, European, and later North American, visitors became more common in Alta California, and their collective observations provide us with a closer look at the tiny Spanish province. French, Russian, English and American visitors alike were astonished at the frailty of the Spanish hold over the area: they found Alta California to be a society without schools, without manufactures, without defenses, administered by a military governor and a quasi-feudal mission system, and inhabited by a population that barely exceeded 1500. Travellers complained of difficulties in obtaining supplies, lack of transportation, and absence of skilled workmen, poor houses and furniture, sour wine, indifferent food, and persistent fleas. So backward was the region, they sniffed, that the plows and oxcarts seemed holdovers from medieval times. So disorganized were the Californios that dairy products had to be secured from the Russian colony at Fort Ross and leather shoes were shipped from Mexico, and later Boston. George Vancouver, the British commissioner sent to implement the Nootka Treaty, visited California three times between 1792 and 1794, and appeared scandalized that the tiny presidios of San Diego and Monterey, Santa Barbara and San Francisco, should represent the European presence in California. Few of their cannon were functional, due to exposure to the elements and neglect, and so scarce was the supply of gunpowder that Commandant Sal in San Francisco had been forced to borrow enough from the Russians to fire a salute in Vancouver’s honor. Earlier, in 1786, the Comte Jean Francois Galaup La Perouse, a French geographer, echoed the same sentiments. Perouse felt that California needed intervention if it were to have a society worthy of its beauty, but predicted that another century would pass before this occurred since California was so isolated.29

As first expressions of how California struck the foreign imagination, these accounts went far to shape the expectations of those who followed these explorers to California. Taken together, they allow us to make certain conclusions regarding the society of late Spanish California. First, California society was poor, backward, and small. While the Californios remained confined to a small coastal strip, within that area, however, they were widely dispersed, thanks in large part to the development of the rancho economy. Taking Santa Barbara as an example, by 1800 nearly half of the 850 residents were reported to be living on ranchos outside the city, a situation duplicated throughout the province. Thus, California was far more rural than metropolitan areas such as Mexico which were dominated by a network of towns.30 Because most of the Spanish land grants were located in the central part of the province, where sufficient water and excellent grazing conditions were available, this area progressed at the expense of the northern and southern regions, antedating a regionalism which is still evident in the state to this day. The failure of the Spaniards to explore the Central Valley of the foothills of the Sierra Nevada range meant that gold was not discovered until after the period of Spanish control and insured the preservation of this ranching and agricultural economy.

Second, Californio society was far from aristocratic and only nominally Spanish, being populated almost exclusively by the poor and low-born of Mexico. While a large plebian group characterized societies as different as those of Bourbon Mexico and Tudor England, the ability of this group to transcend its social limitations made California society unique. Unlike most socially stratified areas, the availability of land and the need for trained administrators allowed certain members of the lower social groups exceptional opportunities for upward social mobility, well beyond the prescribed limits generally granted to plebians. Although rank and skin color counted in the definition of social status, they were not absolute determinants. An excellent example of this is the presidial soldier, who rose largely on the basis of talent and loyalty to the Crown. Arriving in California with a status which was both ethnically and corporatively-derived, the presidial achieved considerable mobility through the presidial command structure, due in large part to the military nature of early California. Through the grant of land from the King, the soldiers gained new prestige as a provincial aristocracy. Lacking competition from a commercial or entrepreneurial group, the soldiers married and began large families which retained a pre-eminent position in the province long after Spanish rule had disappeared.

A list of the most influential men in the late Spanish and early Mexican periods of California history indicates this upward mobility. Jose Dario Arguello, for example, arrived as an enlisted man from Queretaro, Mexico where he had been born of undistinguished parentage. After serving eight years in the ranks his administrative talents won him a commission and command in Santa Barbara and later San Francisco. He was later appointed interim governor. This process was followed by his son Luis Antonio who was able to secure a cadetship and a commission within two years of entering service, becoming the commandant of the four Southern California missions and the owner of a 50,000 acre ranch in the Mission Valley area of San Diego.

The Arguello story is typical, it would seem. The fathers of the Mexican governors Alvarado and Pico and of the Generals Vallejo and Castro had all begun as presidials, as were the founders of the important California houses of De la Guerra, Ortega, Peralta, Valencia, Sanchez, Bernal, Alviso, Galindo, Carrillo, Moraga, and others.

Finally, and perhaps most important, this extreme social mobility infused California society with certain characteristics which have continued to persist long after the Spanish period. Foreign visitors and Spanish governors alike recognized that California was a unique area, although they disliked and disagreed with many of its features. In 1794, the jovial Basque Governor Diego de Borica filed glowing reports on the province to his Mexican superiors, calling it “a great country, the most peaceful and quiet in the world,” where “one lives better than in the most cultured courts of Europe.” Blessed with sufficient water, fertile soil, and a good climate, Borica noticed that all who remained there “are getting to look like Englishmen.”31

Although it is likely that Borica’s remarks were designed to help in finding him a willing replacement, his conception of the province probably squared more nearly with that of the first Californios themselves than did the European travellers’ generally unfavorable accounts of the province. Because of their poor backgrounds and the almost complete lack of opportunity afforded these soldiers and settlers in their native Mexico, they were grateful for the opportunity to receive land and remain in California. Not only did the Crown offer them a chance to improve themselves, but the granting of land transformed these men into rancheros which immeasurably improved their social position and allowed them an opportunity for profit through trade with foreign visitors who began to arrive in increasing numbers after 1800. Within the space of a single generation the presidial group at least had begun to transform itself into something quite resembling a provincial aristocracy, although a relatively poor and remotely located one to be sure.

Many historians have developed the story of Mexican and Anglo-California after 1846 as the ultimate frontier, or, to use the words of Kevin Staff, “the cutting edge of the American Dream.”32 This short paper has attempted to illustrate that dreams of a better future and the hope of self- determination, while usually associated with the Anglo-American culture, are not the exclusive preserve of that civilization. This is a point well worth remembering, not in order to diminish our own achievements, which were formidable indeed, but simply to extend them to include persons of other climates and cultures who struggled in a sometimes quite similar fashion to achieve a better life for themselves.

Spaniards in sixteenth century New Spain had created California as a province of the mind, both a concept and an imaginative goal, immediately following the conquest of Mexico. For two centuries afterwards the dream was sorely tested as Spain moved forth into other areas in pursuit of mineral wealth and high Indian civilizations. With the exploration and conquest of the Pacific Coast in the eighteenth century the dream was revived by a small group of presidial soldiers who successfully transformed themselves into a ranchero aristocracy. Far from the metropolitan capital of Mexico City, California largely avoided the revolutionary movement which had swept Spanish South America.33South American independence had occured in 1826 partially at least as a result of the conquistadores‘ failure to establish a seigneurial society, something their creole descendents continued to demand from the Spanish ruling groups. In California, however, the inhabitants were able to create a pale image of a landed society almost free of Spanish control. Located far from Mexico, on the very rim of Christendom, the province was freed from the vicissitudes of imperial politics. For this reason as much as any, Mexican rule was quietly accepted in California in 1822. The Californios had successfully created a way of life that met their expectations. It is one which has symbolically been preserved to this day and one to which many Californians still aspire.

Footnotes

1. Frederick Jackson Turner, The Frontier in American History (New York, 1962),

2. Robin A. Humphreys, “The Fall of the Spanish American Empire,” History, 38 (1952), 213.

3. Herbert Eugene Bolton, “The Epic of Greater America,” American Historical Review, 38 (1933), 448-474.

4. Zoeth S. Eldridge, The Spanish Archives of California (San Francisco, 1901), p. 8.

5. Bernard De Voto, The Year of Decision, 1846, 2nd ed. (Boston 1961), p. 13; Leonard Pitt, The Decline of the Californios: A Social History of the Spanish-Speaking Californians, 1846-1890 (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London, 1971), p. vii.

6. Oakah L. Jones, Jr. ed., The Spanish Borderlands: A First Reader (Los Angeles, 1974), pp. 9-10.

7. Nellie Van De Grift Sanchez, Spanish Arcadia in California (Los Angeles, 1929).

8. Carey McWilliams, “Why the Cult of the Missions?” in Davis Dutton, ed., Missions of California (New York, 1972), pp. 149-150.

9. Leonard Pitt, The Decline of the Californios, pp. vii-viii.

10. See the bibliography on “Exploration” and “The Church” in Jones, The Spanish Borderlands, pp. 243-244. Charles E. Chapman, A History of California: The Spanish Period (New York, 1921), pp. 388-389.

11. James Lockhart, “The Social History of Colonial Latin America: Evolution and Potential,” Latin American Research Review, 8:1 (Spring, 1972), 6.

12. Herbert I. Priestley, Jose de Galvez: Visitador-General of New Spain, 1765-1771 (Berkeley, 1916).

13. See John Francis Bannon’s The Spanish Borderlands Frontier, 1513-1821 (New York, 1970), pp. 143-166.

14. Charles F. Lummis, “Regulations and Instructions for the Garrisons of California, 1781,” The Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly, 42: 1 (1960), 90-92. This supplemented the 1772 regulations for the frontier military units of northern New Spain, translated in Sidney B. Brinkerhoff and Odie B. Faulk, Lancers for the King (Phoenix, 1965), pp. 9-67.

15. Problems of supply are discussed in Charles E. Chapman, “The Alta California Supply Ships, 1773-1776,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly, 19: 2 (1915), 184-194, and Max L, Moorhead, “The Private Contract System of Presidial Supply in Northern New Spain,” Hispanic American Historical Review, 41: 2 (February, 1961), 31-54.

16. Census data for colonial California are rare and vary considerably. See the padrones (censuses) in The Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly, 42:2 (1960), 210-211; 42:3 (1960), 313; The Historical Society of Southern California Annual, 16 (1931), 148- 149; Carey McWilliams, North from Mexico: The Spanish-Speaking People of the United States (New York, 1968), pp. 89-90.

17. The social backgrounds of the presidials are described in Leon G. Campbell, “The First Californios: Presidial Society in Spanish California, 1769-1822,” Journal of the West, 11: 4 (October, 1972), 582-595.

18. The published correspondence of the Franciscan fathers is replete with criticism of the soldiery. See, for example, Zephyrin Engelhardt, The Missions and Missionaries of California, 4 vols. (San Francisco, 1908-1915). The priests resented that the governor held control over the soldiers, which restricted their control over the men.

19. Walton Bean, California: An Interpretive History (New York, 196 8), pp. 40-41. References to the friars can be found in the governors’ correspondence, located in the Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley, California Archives, Provincial State Papers, vols. 1-3.

20. Social derivations can be established from the biographies in Hubert Howe Bancroft, Register of Pioneer Inhabitants of California, 1542-1848 (Los Angeles, 1964). I have based much of my information about the soldiery on their service records, located in the Archivo General de las Indias in Seville, Seccion Audiencia de Lima, Legajo 1503 (hereafter AGI: AL 1503).

21. Bean, California, p. 43.

22. Campbell, “The First Californios,” 591-592.

23. “Duhaut-Cilly’s Account of California in the Years 1827-1828,” California Historical Quarterly, 13 (1929), 311. The author was a French naval officer.

24. Max L. Moorhead, “The Soldado de Cuera: Stalwart of the Spanish Borderlands,” Journal of the West, 8: 1 (January, 1969), 53.

25. See, for example, the case of New Mexico, in Marc Simmons, “Settlement Patterns and Village Plans in Colonial New Mexico,” in Jones, The Spanish Borderlands, pp. 54-69.

26. Landholds to presidials is described in William W. Robinson, Land in California (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1948), pp. 45-58, and in Campbell, “The First Californios,” 592-593.

27. Janet R. Fireman, “Mentality of an Innocent Bystander: Reaction in Spanish California to the American Revolution,” paper presented to the Fourteenth Annual Conference of the Western History Association, Rapid City, South Dakota, October 5, 1974.

28. The Cook expedition and the Anglo-Spanish conflict over the northwest are described in Warren L. Cook, Flood Tide of Empire: Spain and the Pacific Northwest, 1543-1819 (New Haven and London, 1973).

29. An excellent summation of these visitors’ accounts is provided in Kevin Starr, Americans and the California Dream, 1850-1915 (New York, 1973), pp. 3-48. For a detailed analysis of the Nootka conflict between Spain and Great Britain, see W. R. Manning, “The Nootka Sound Controversy,” American Historical Association Annual Report, 1904 (Washington, D. C., 1904), pp. 279-478.

30. See, for example, D. A. Brading, “Government and Elite in Late Colonial Mexico,” Hispanic American Historical Review, 53: 3 (August, 1973), 389-414.

31. Cited in Bean, California, pp. 53-54.

32. Besides the work of Pitt, on the decline of the Californios after 1846, see Starr’s superb analysis of the development of the American Dream in the province, Americans and the California Dream, pp. 46-48.

33. See George Tays, “Revolutionary California: The Political History of California During the Mexican Period, 1820-1848,” unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 1934.

Suggested further reading

Edwin A. Beilharz, Felipe de Neve: First Governor of California (San Francisco, 1971).

John Francis Bannon, The Spanish Borderlands Frontier, 1513-1821 (New York, 1970).

Herbert L. Bolton, “The Mission as a Frontier Institution in the Spanish American Colonies,” American Historical Review, 23:1 (October, 1917), 42-61.

Sidney B. Brinckerhoff and Odic B. Faulk, eds., Lancers for the King: A Study of the Frontier Military System of Northern New Spain, with a Translation of the Royal Regulations of 1772 (Phoenix, 1965).

Leon Campbell, “The First Californios – Presidial Society in Spanish California, 1769-1822,” Journal of the West, 11:4 (October, 1972).

Sherburne F. Cook, The Conflict Between the California Indian and White Civilization, 2 vols. (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1943).

Warren L. Cook, Flood Tide of Empire: Spain and the Pacific Northwest, 1543-1819 (New Haven and London, 1973).

Alberta Johnson Denis, Spanish Alta California (New York, 1927).

George H. Elliot, “The Presidio of San Francisco,” Overland Monthly Magazine, (1870).

Jack D. Forbes, “Black Pioneers: The Spanish-Speaking Afro-Americans of the Southwest.” Phylon, 27:3 (Fall, 1966).

Maynard Geiger, The Life and Times of Fray Junipero Serra, 2 vols., (Washington, D.C.). The Geiger book is not documented but scholars can easily check the author’s sources by referring to the nominal indices of the California Mission Documents and the Serra Collection in the Santa Barbara Mission Archives. Also see Antonine Tibesar, ed., The Writings of Junipero Serra, 4 vols., (Washington, D.C., 1955-1966).

Maynard Geiger, “A Description of California’s Principal Presidio, Monterey, in 1773,” Southern California Quarterly, 49: 3 (1967), 327-336.

Charles Gibson, Spain in America (New York, 1966).

Florian F. Guest’s unpublished doctoral dissertation, “Municipal Institutions in Spanish California, 1769-1821,” University of Southern California, 1961, which is partially surmmarized in the same author’s “Municipal Government in Spanish California,” California Historical Society Quarterly, 46: 4 (1967), 301-336.

Kibbey M. Horne, A History of the Presidio of Monterey (Monterey, 1970).

Max L. Moorhead’s The Presidio: Bastion of the Spanish Borderlands (Norman, Oklahoma, 1975), is a model study for the institution in the Spanish Southwest but excludes study of the California and Florida presidios because of the differences involved.

Max L. Moorhead, “The Soldado de Cuera: Stalwart of the Spanish Borderlands,” Journal of the West, 8:1 (January, 1969), 38-55.

Donald A. Nuttall “The Gobernantes of Spanish Upper California: A Profile,” California Historical Society Quarterly, 51: 3 (Fall, 1972).

George Harwood Phillips, Chiefs and Challengers: Indian Resistance and Cooperation in Southern California (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London, 1975).

Russel A. Ruiz, “The Santa Barbara Presidio,” Noticias, 13:1 (1967), 1-13.

Manuel P. Servin, “California’s Hispanic Heritage: A View into the Spanish Myth,” Journal of the San Diego Historical Society, 19:1 (Winter, 1973).

Manuel P. Servin, ed., “Costanso’s 1794 Report on Strengthening New California’s Presidios,” California Historical Society Quarterly, 49:3 (September, 1970), p. 229.

Maria del Carmen Velazquez, Establecimiento y perdida del septentrion de Neuva Espan (Mexico, 1974).

Excellent record groups for the study of the Alta California presidios exist in the Archivo General de ]as Indias in Seville and the Archivo General de la Nacion in Mexico City. The transcriptions of the Spanish Archives of California, made by Hubert Howe Bancroft and his associates, and a variety of other primary data are available in the Bancroft Library at the University of California at Berkeley. Mission and chancery archives are also valuable sources for the study of presidios. A wealth of information on presidial population and social structure is to be found in the Zoeth Eldridge Collection and the California Mission Collection of the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley.

The regulation governing the conquest of California is found in Archivo General de la Nacion (AGN): Seccion Provincias Internas, Legajo 166, 3. A series of military crimes reaching trial covering the period 1773–1779 are located in AGN: Californias, Vol. 2, Part 1, folios 244-293.