Contents

Contents

Sitting in his room somewhere in the city of Strasbourg in the summer of 1788, Georg Daniel Flohr finally put down his quill. In front of him lay a stack of manuscript pages. Filled with gothic script in the author’s native German and adorned with brightly colored illustrations, they contained his Account of the travels in America which were made by the Honorable Regiment of Zweibrucken on water and on land from the year 1780 to 1784. Exactly one year had passed since he had completed the elaborate title page on June 5, 1787, and the “Specification in English,” tucked in almost as an afterthought between the preface of the work and the title. Still single and rapidly approaching his 32nd birthday, Flohr must have spent some time of reflection on the turn of events 12 years earlier, on June 7, 1776.

On that date Flohr made a decision that would change his life forever: He enlisted for an eight-year term in the Deutsches Koniglich-Franzosisches Infanterie-Regiment von Zweybrucken, or Royal-Deux-Ponts. Royal-Deux-Ponts, one of 22 foreign regiments in the French army, was a young regiment. Established in April of 1756 by Duke Christian IV of Zweibrucken, it was only a few weeks older than its latest recruit, who had been born on August 27, 1756, in Sarnstall, a tiny village of some 20 families near Annweiler in the Duchy of Zweibrucken. Nothing is known of Flohr’s trade or education, or why he joined the regiment. Was it the enlistment bonus that tempted the young man, who had been orphaned at age five by the death of his father, a butcher and small farmer, and who had been raised by the widowed mother? Was it the prospect of free instruction in reading and writing, dancing and fencing, promised by recruiters? Or was it simply the desire to see the world, to follow the example of David Wittmer, who had enrolled on April 29, 1776, and that of other acquaintances from Sarnstall and Annweiler who were serving with Royal-Deux-Ponts?

In this same summer of 1776, events across the Atlantic Ocean would make certain that Flohr was to get his wish. On July 4, 1776, the British colonies in North America declared their independence from the mother country. As war broke out, volunteers and adventurers, some more sincere than others, from all over Europe offered their help, among them the Marquis de Lafayette. His connections to the court of Versailles were instrumental in bringing about the Franco-American Treaty of Friendship of 1778 and the promise of military aid.

In the fall of 1779, France decided to send an expeditionary force under the command of General Rochambeau to aid the hard-pressed Americans. One of the regiments chosen to cross the Atlantic was the Royal-Deux-Ponts. In April of 1780, the French troops embarked from Brest for Newport, where they arrived in July. Sixty-nine officers, 1,013 noncommissioned officers and men, six soldier’s wives, and three children from Royal-Deux-Ponts were among the roughly 6,000 French troops who made the dangerous journey.

Flohr was aware of the enormous educational possibilities provided by his grand tour, courtesy of the king of France. Almost immediately he began to keep notes of events, “daily and most meticulously,” to gather information on what he heard, and to draw sketches of what he saw. During his three years in the New World he collected enough material to fill 251 pages of text and 30 pages of illustrations in a journal describing his travels in America.

His account is largely descriptive in nature. Flohr apparently cared little about politics or the military trade and, with the exception of the siege of Yorktown, his journal is largely devoid of scenes of the military life. Rather he was interested in “the towns, villages, hamlets and plantations” and in the inhabitants “of North – as well as in West – America,” their customs, and modes of life. His journal presents a fascinating picture of life in Revolutionary America as it appeared to a young European peasant, an image of colonial America from the bottom up. His observations on Virginia, where the French forces spent almost 10 months from September 1781 to July 1782, and where the decisive battle of the war was fought, add a new perspective to the accounts provided by officers.

After a rather uneventful year in New England, highlighted only by the visit of Iroquois Indians to Rochambeau’s camp in August 1780, the troops were told in early September 1781 that they were to march to Virginia and “a small town by the name of Little York,” where “the General Kornwallis of the English had dug in with 12,000 men, ravaging the country very badly.” On September 28 the siege began; on October 9 French and American artillery opened fire on the defenders. “We could see from our redoubt the people flying into the air with outstretched arms,” Flohr wrote. “There was a misery and lamenting that was horrible…The houses stood there like lanterns shot through by cannon balls.”

On October 14 grenadiers and chasseurs of Gatinais and Royal-Deux-Ponts with Flohr among them stormed Redoubt #9, heralding the last stage of the siege. Again, he wrote, “things went very unmercifully that night…One screamed here, the other there, that for the grace of God we should kill him off completely. The whole redoubt was so full of dead and wounded that one had to walk on top of them.” Five days later Cornwallis surrendered, and the troops inspected the damage they had done. “The whole ground was so turned up and full of holes…that one could barely walk. Wherever you looked corpses were lying about that had not yet been buried, the majority of which were blacks. The camp of the [English] army in and about the city resembled a veritable scene of destruction.”

After the prisoners had been sent off and defensive works razed, the French moved into winter quarters around Williamsburg and Jamestown on November 16, 1781. “Here we remained throughout the winter, and we felt quite at home there.” Three companies of Royal-Deux-Ponts under Lieutenant-Colonel Ludwig Eberhard von Esebeck were sent to Jamestown Island, “a desert island,” where the buildings had been “almost entirely destroyed by the English who left barely the four walls,” as Esebeck reported to his brother in Zweibrucken. But once the French had established themselves, Esebeck was “enchanted with it. The place is beautiful,” despite the destruction all around.

Flohr, too, thought that the companies around Jamestown were well taken care of, “since it is a very pleasant area.” But Jamestown itself, “a little village and one of the oldest settlements in America,” was in ruins. “It used to be a nice trading town, but it is now completely ruined. But there are signs, still visible, that it once was a sizeable city, about six miles from Williamsburg.”

Flohr and his company received quarters in Williamsburg, “a pretty little town,…where the English ViceRoy had his seat or residence while it was still English.” The arrival of hundreds of foreign officers, and their cash, transformed this town of some 1,500 inhabitants into a center of social life. “Were it not for the French officers it would be a dead calm,” Peter Colt reported to his family in Wethersfield, Connecticut, in March 1782. But the staid Yankee added quickly that “when we depart the inhabitants may starve.” According to Colt, Virginians were foolishly, if not immorally, spending much needed funds in a “universal Spirit of gambling, Hors-racing and other expensive Diversions.”

Unlike the morally upright Colt, the noble officer corps enjoyed the lifestyle of the tidewater gentry. Baron Closen, a captain in Royal-Deux-Ponts, thought that the fair sex of Virginia was not only the prettiest in all of America, but that they danced the minuets “infinitely better than those up North.” If he thought the cockfights “a little too cruel,” he and his fellow officers from Rochambeau on down thoroughly enjoyed the fox hunts. If there was any complaint, it was that the hunts were over too soon: “the species of foxes is not as strong as that in Europe.”

While officers chased foxes, Flohr found out how Virginians hunted beavers: they flooded their ponds at night when the beavers were home and then drained them. “As soon as the water recedes again, they come out…and then they can be shot.”

“Virginia,” according to Flohr, “is one of the largest provinces among the thirteen colonies in all of North America, but still has very few inhabitants, which is why the German Europeans are very welcome there.” It was not just the emptiness of the country which lay behind this attitude – the large number of black slaves was also partly responsible.

“In Virginia there are the richest Gendelmanner of the whole country, who own up to 150 and more slaves, or rather Mohren.. These moors are supervised by white overseers to do the work of their masters. One can see them at work, men and women, young and old, without clothes on…On the cotton fields one could see up to 100 and sometimes even more moors harvesting cotton for their masters.”

Flohr felt ashamed for the blacks, but white Virginians, even “the white women,” did not seem to notice the nakedness of the slaves. When asked about it, “they answered me that if we had to clothe all these blacks it would cost us too much, and the clothes would be torn again in three to four weeks, and that they (the slaves) were not worth that expense.” Flohr was greatly upset by the treatment of the blacks, who “were kept just like cattle, and the children of the blacks are raised in a state of nature just like the young cattle. The more young ones they make, the better for the master who owns them.” Flohr did not want to go into any more detail, since he thought the system “completely against human nature.”

Officers may have questioned some of the manifestations of slavery but never the system as such. The Comte de Clermont-Crevecoeur thought that “Virginians are quite cruel to their slaves,” who, in the words of Baron Closen, were “not considered to be much better than animals.” But Closen also thought them “thievish as magpies,” and Clermont-Crevecoeur considered them “naturally lazy.” “Such severity, which seems inhuman to a European, is necessary,” at least in the opinion of Louis Alexandre de Berthier. After all, he continued, “the slaves are sure of being cared for and fed to the end of their lives.”

But Flohr did more than watch the slaves. While the officers toured the country estates of Virginia, Washington’s Mount Vernon or Jefferson’s Monticello, the soldiers were restricted in their movements. Flohr used the time on his hands to look around his winter quarters:

“The city of Williamsburg lies on a plain in a beautiful country and is also rather large. It is also adorned with a few beautiful buildings, which are the College with two wonderful adjacent buildings. There is also the Capitol which is parallel to the college on the other end of the city. In addition there is also the building of the Vice-Roy who resided there when it was still British. There is also the Doll House, also a beautiful large building, and there is also a beautiful church-tower.”

In the Capitol Flohr also saw the statue of Governor Norborne Berkeley, Baron de Botetourt, which is today in the Swem Library of the College of William and Mary. “There in the Capitol can also be seen in life-size the old Vice-Roy, cut out of marble in a very remarkable way. The marble is as white as snow. On the bottom of the statue his name can be seen, written in golden letters on black marble in English and in Latin. He is also buried in this very same building.”

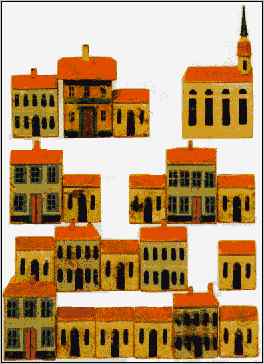

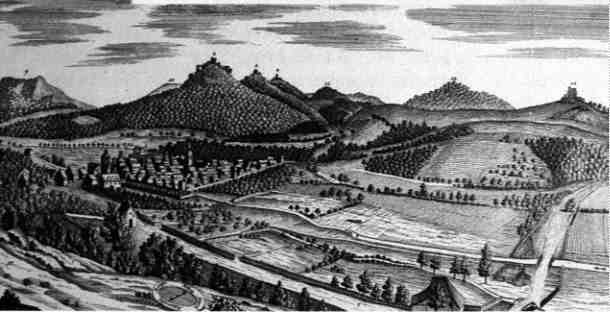

Throughout the journal, Flohr enhanced his verbal accounts with drawings of the towns he visited and the countryside he marched through. These drawings are folk art impressions of colonial America by a talented but untrained artist. They were not meant to provide accurate depictions of every detail. With the exception of such buildings Flohr thought noteworthy or that stood out in his memory, the landscape and buildings are highly stylized. All buildings, but especially the little houses he drew to fill up space in between the structures he wanted to emphasize, resemble model houses similar to modern ones we would use today for toy-train landscapes.

More decorative than literal, Flohr’s depictions of houses resemble wooden toys like those (above) in the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center collection. Perhaps, the author speculates, “FIohr played with similar toys as a child.”

Examples of German wooden toy houses, most dating from the 19th century, bear remarkable resemblance to those seen in Flohr’s drawings. Such toys were likely made in Germany as early as the late 18th century. Maybe Flohr played with similar toys as a child and still remembered them as an adult when he painted the pictures for his manuscript in the 1780s.

One of the most interesting and detailed drawings of the journal is the picture of Williamsburg as it would have appeared to Flohr in late 1781. Any visitor to Williamsburg will immediately recognize the historic landmarks depicted: the College of William and Mary with the President’s House on the left, the Wren Building in the center, and the Brafferton, used to educate Indian children, on the right. The other buildings mentioned are the Capitol and Bruton Parish Church. The Doll House is undoubtedly the Insane Asylum (toll meaning insane, mad, raving in German). But the most interesting feature of the drawing is the low arched building to the left of the asylum. It is identified by Flohr as Die Halle, the Market Place.

Flohr found the college “pretty and remarkable” though it had been “established by the King of England (as) a place to study” much earlier than “in 1756.” But “because of the war it had been completely neglected, and the French used it for a hospital.”

Until the transformation of the college into a hospital, the wounded had been lying “on straw in a poorly closed barn” in Yorktown. Here “they die of cold,” according to the Chevalier de Chastellux, a major general in Rochambeau’s army. On October 21, 1781, he requested transportation to Williamsburg for some 25 wounded with “terrible fractures caused by the explosions of bombs and cannon shots.”

Yet the wounded would not stay there for long. On November 23 the President’s House burned down, “set on fire by the French, who had to pay for it.” A few weeks later, on December 22, the Governor’s Palace, already badly damaged during the war and used as a hospital by the Americans, also burned down. According to Flohr, some of the sick and wounded perished in a fire caused by American negligence. In the course of the winter many soldiers, including 18 of Royal-Deux-Ponts, died in Williamsburg. Today their names are inscribed on a plaque on the back of the Wren Building.

On July 2, 1782, the French forces departed from Virginia and arrived in Boston in early December. On Christmas Day they set sail for the Caribbean and would not return to France until June 1783. Discharged in August 1784, Flohr moved to Strasbourg, where he compiled his journal between June 1787 and June 1788. In the spring of 1789 he departed Strasbourg for Paris to study medicine under an uncle. The manuscript was left with a half-brother in Sarnstall. From one of his descendants it found its way into the collections of the Bibliotheque Municipale in Strasbourg sometime after September 1870, where it lay forgotten for more than 100 years until rediscovered in the 1970s.

AND GEORG DANIEL FLOHR?

Shortly after his arrival in Paris, the Great Revolution broke out. By the summer of 1792 the Jacobins had come to power, and in January 1793 Louis XVI was executed. Flohr, who witnessed the event, decided to give up medicine, quit France, and return to that “most beautiful country,…so pleasant that any body could have liked to stay there,…where all people are rich and well,” and where “the German nation” was held “in very great esteem.”

By the mid-1790s we find him in Madison County, Virginia, studying theology with the Reverend William Carpenter. Licensed as a Lutheran minister in 1799, ordained in Baltimore in 1803, Flohr took up residence in Wythe County, Virginia.

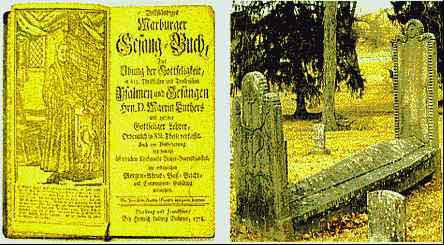

For the next 27 years he served half a dozen congregations as far away as Lewisburg in then Greenbrier County, West Virginia. When he died in 1826, his parishioners carried the coffin on their shoulders the mile and a half from the parsonage to the cemetery. Stonemason Lawrence Krone carved a unique coffin-shaped marker with a footstone and headstone, still visible in St. John’s cemetery in Wytheville. Holy Trinity Lutheran Church still owns some of his hymnals, and in 1984 his house was moved onto church grounds to save it from destruction.

Above, Flohr’s home in Wytheville, Virginia.

His grave (above right) is nearby. The hymnal (above left) dated 1778 was likely used by Flohr. It is preserved at Holy Trinity Lutheran Church in Wytheville, Virginia.