The following is a chapter from the book “The Private Soldier Under Washington” written by Charles Knowles Bolton in 1902. The book helps to explain the conditions that Continental soldiers experienced during the American Revolution.

The book contains fascinating letters and notes written by soldiers during the war, which you may find contain some outdated spellings of certain words compared to modern English.

Chapters

- Chapter 1: Origins of the Continental Army

- Chapter 2: How the Continental Army was Maintained

- Chapter 3: Supplying the Continental Army

- Chapter 4: How the Continental Army Armed Itself

- Chapter 5: Camp Duties in the Continental Army

- Chapter 6: Officers vs Privates in the Continental Army

- Chapter 7: Distractions & Passing the Time in the Continental Army

- Chapter 8: Hospitals and Prison Ships in the Continental Army

- Chapter 9: How the Continental Army Moved

- Chapter 10: Continental Army Privates

The Scylla and Charybdis of the soldier were the hospitals of his own army and the prison-ships of the enemy. Perhaps the knowledge of this made the life in camp and on the road more endurable than it would otherwise have been. To see the dawn over a hilltop drove out the depression that comes with the night, and to stand in the full radiance of the warm sun at noonday baffled malaria and stayed the march of disease. But the sun and the stars never came to the sufferer upon his sick-bed, nor often to the half-crazed, half-naked creature in his marine prison-pen.

The health of the men in camp was not forgotten, although the means of checking contagion and alleviating pain were inadequate, and many of the household remedies of to-day were then still to be discovered. In continued bad weather a half gill of rum was issued to each of the men, and they were cautioned against drinking new cider and also the water of streams forded during the heat of the day.1 The air of the huts and tents was purified by burning the powder of a blank musket cartridge daily, or by lighting pitch or tar;2 the hospitals were treated in the same manner.

In many of the hospitals where there were few beds or blankets and no medicine or nurses, the service was not much more than the presence of a doctor until death came. Colonel Wayne, writing to General Gates in December, 1776, said: “Our hospital, or rather house of carnage, beggars all description, and shocks humanity to visit. The cause is obvious; no medicine or regimen on the ground suitable for the sick; no beds or straw to lay on; no covering to keep them warm, other than their own thin wretched clothing.”3 At this time the deaths came so rapidly that the living grew weary of digging graves in the frozen earth. “A scene something diverting, though of a tragic nature,” as Lieutenant Elmer puts it, occurred in consequence. Two graves had been dug with much labor by men of the New Jersey line for their dead; but when they, having gone for the bodies, came back prepared to bury their comrades they found that some Pennsylvanians had come upon the open graves, and finding no one near, deposited their own dead there and covered them with earth. A hot dispute ensued and the New Jersey troops succeeded in digging up the other bodies, which were thrown under a heap of brush and stones.4

Good doctors and faithful ministers were rarely wanting in the camps; and they went about where men lay tossing from side to side on sacks of straw or grass, and did much to comfort the sufferers.

“My heart is grieved,” wrote Rev. Ammi R. Robbins, “as I visit the poor soldiers – such distress and miserable accommodations. One very sick youth from Massachusetts asked me to save him if possible; said he was not fit to die: ‘I cannot die; do, sir, pray for me. Will you not send for my mother? If she were here to nurse me I could get well. O my mother, how I wish I could see her; she was opposed to my enlisting: I am now very sorry. Do let her know I am sorry!'” Mr. Robbins was a devoted chaplain, who had to nerve himself constantly to bear the foul air that injured his health and the tales of sorrow that burdened his heart. He believed that the war was waged in a just cause, and when the men of whole congregations went out to battle, he felt that ministers should be ready to nurse their sick and bury their dead.5

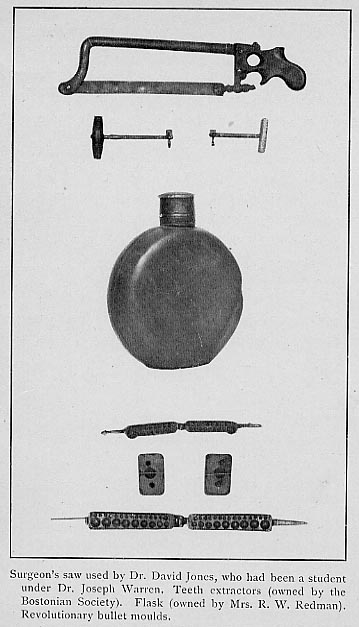

At Saratoga an officer from each regiment was appointed weekly to visit every day the men from his own corps scattered through the hospitals.6 But this care availed little when medicine and surgery were not always represented in camp by able physicians;7 and antisepsis and anaesthetics were unknown. Cleanliness in conducting difficult operations was not insisted upon as it is to-day, and the wounds made by large round bullets moulded by hand needed the very best of treatment.8 Putrefaction and pain ran riot in the emaciated bodies of the soldiers, and many who survived never regained their health.

The kind of medicine recommended by a doctor’s wife may prove of interest. From a soldier’s description of his sick friend’s condition she thought the trouble might be “gravels in the kitteney,” as the diarist wrote the name, and she ordered a “quart of ginn and a tea dish of muster seed, and a hand full of horseradish roots – steep them togather and take a glass of that every morning.” The gallant fellow submitted to this new affliction, and happily was able to report that “he found benefit by it.”9 The truth is that much of the illness came from a longing to be at home, from hunger, and from cold. Referring to the first of these causes of army sickness, General Schuyler once said: “Of all the specifics ever invented there is none so efficacious as a discharge, for as soon as their faces turn homeward nine out of ten are cured.”10 For the other tenth, just referred to, the remedy used at Valley Forge, mutton and grog,11 proved to be as useful as anything to aid in resisting the germs of disease that everywhere threatened the camp with pestilence. In the Quebec expedition, when exposure and hunger had prepared the way, a fourth or third of the men in some regiments died of small-pox.12

From the records of the general hospital at Sunbury, Penn., for 1777-80, it appears that about four-tenths of the patients (not counting the convalescents) were the wounded; about three-tenths suffered from diarrhoea or dysentery, and one-tenth from rheumatism.13 To state this in another form, lack of proper food and shelter crippled the army as much as did the fire of the enemy. The number of cases treated, however, was not large enough to give very accurate statistics.

The sick suffered from crowding and from an insufficient supply of medical stores; those on the upper floors of hospitals had little or no ventilation, and at Bethlehem four or five invalids, one by one, occupied the unchanged straw until death came like an angel of mercy.14 It is perhaps not very strange that communities did not want army hospitals, and the arrival of open wagons in which lay groaning soldiers, wet with rain and snow, was the signal for vigorous protests from the populace. As soon as the patients were able to walk they were told that there was too little food to make a longer stay desired, and they were sent out penniless and weak to walk the country roads, begging from house to house.15 This in itself was an objection to the presence of a hospital in a neighborhood.

In such a state of poverty, the support of a minister seemed an expense that could be avoided, and few were found in the hospitals at New Windsor, West Point barracks, Morristown, Albany, Philadelphia, Fishkill, Yellow Springs, Williamsburg and Trenton, where many were often needed.16

Sickness and inadequate hospital facilities had a very direct effect upon the conduct of the war. Every haggard soldier who returned to the village of his birth was a silent force, decreasing enlistments and increasing the amount of bounty to be wrung from the taxpayers; this was particularly true at the South in the winter of 1776-77.17 The commissariat was the great arbiter of events during the Revolution; insufficient food caused disease and desertion, crippling the army until Washington was forced to keep to a Fabian policy that irritated those who were unfamiliar with the obstacles in his path.

If the Continental soldier in the hospital of his countrymen had reason for discontent, he might well believe that he would fare even less happily in the hands of the British, who rarely were able to make adequate provision for their prisoners. After the retreat from New York in 1776 the churches of the town were crowded with starving Americans; some with dull eyes and parched, speechless lips sat upright and sucked bits of leather or wood-the last act of a reason almost extinct, and others lay upon the bodies of their comrades, gnawing bones and begging their keepers to kill them.18 While the helpless creatures were in this condition the sentries were said to have annoyed them needlessly.19 The description of prison-life in Philadelphia during the British occupation is too ghastly to be credible in all its details. Dr. Albigence Waldo, of Washington’s army, who has been quoted frequently in these pages, complained that the enemy did not knock their prisoners in the head, or burn them with torches, or flay them alive, or dismember them as savages do, but they starved them slowly in a large and prosperous city. One of these unhappy men, driven to the last extreme of hunger, is said to have gnawed his own fingers up to the first joint from the hand before he expired; others ate the mortar and stone which they chipped from their prison-walls, while some were found with bits of wood and clay in their mouths which in their death-agonies they had sucked to find nourishment.20

One must keep in mind the fact that nearly all contemporary authorities were influenced by the bitter spirit of the times to over-color their pictures of the suffering which came with war. There were frequent complaints of cruel treatment of prisoners from the commanders of both armies, British and American, and each side hoped to profit by the publicity given to harrowing details. At about the time Americans were enduring privation in New York, in the autumn of 1776, an event occurred at the north which proves that the British could show a magnanimity that might become dangerous to the cause of independence. Arnold’s brave attempt to check the advance of Sir Guy Carleton on Lake Champlain had ended in a furious naval fight and Arnold’s retreat. The American sailors taken by Carleton were treated like friends by the commander and his men. News came to Gates that they had been sent down the lake in boats to his camp, and Colonel Trumbull was accordingly instructed to meet them. Trumbull soon found that the men were enthusiastic over their reception by Carleton and loudly praised the generosity of the British. In alarm he hastened back to tell Gates that the men would work mischief with their tales of a bountiful enemy if allowed to mingle with the soldiers of the army. Trumbull’s view was approved, and the surviving captives were at once ordered southward to Skenesboro on the way to their homes.21

The prison-ships were perhaps less oppressive in summer than the city places of confinement; but at best they were unclean, strictly guarded, and insufficiently supplied with food and medicine.22 Many deaths occurred daily, and on board the Jersey (popularly known as Hell) the morning salutation of the officer was: “Rebels, turn out your dead!”23 The horrors of those days have been pictured so often that it is unnecessary to resketch the sickening details. The living and the dead lay together in the stifling holds of the ships until the time came to bury the latter. These were put beneath the sand on the beach near by, and in the next severe storm they were washed back into the sea to float for days in the hot sun near the port-holes of the prison-ships. In warm weather one man was allowed on deck each night, and the prisoners crowded about the grating at the hatchway to get a breath of air and to be ready when their turn came to go out. The sentinels thrust their bayonets through the grating in sport, and sometimes, it is said, killed one of their prisoners.24

Lest these scenes in the lives of the captive soldiers seem too incredible, it may be well to add the experiences of a man of letters who was famous in his day and is not altogether forgotten in our time – Philip Freneau, the poet of the Revolution. Freneau spent some time in the prison-ship Scorpion which lay in the North River in 1780. The conditions there were so terrible, according to the poet, that any plan of escape, however likely to fail, was tried; while every attempt increased the brutality of the Hessian jailers who were held responsible for their detention. When a number of men had rushed upon the sentries, disarmed them, boarded a vessel near by and escaped, the guards in their chagrin vented their anger upon the remaining prisoners by firing into the hatchways.

Freneau soon came down with a fever and was transferred to the hospital-ship Hunter. Some convalescents on board waited one day the coming of the doctor; when he had gone below they slipped into his boat as it lay alongside, and made a successful escape. The doctor was annoyed and after that, regardless of the sick and dying who had no part in the plan, he passed by the Hunter at a distance on his rounds. An appeal for “blisters,” too loud to be ignored, one day caused him to rest on his oars; he looked up at the eager faces, suggested pleasantly that the sufferers plaster their backs with tar, and rowed on to the ill-famed Jersey.25

In a characteristic letter, written in 1780, from Passy, Dr. Franklin told Mr. Hartley, a peace-loving Englishman, that Congress had investigated these barbarities and had instructed him to prepare a school-book, to be illustrated by thirty-five good engravings, each one to picture a “horrid fact” that would impress the youthful posterity in America with the enormity of British malice and wickedness.26

While patriot soldiers were suffering in city prisons and on the water many captives were beginning years of confinement in Old Mill prison near Plymouth, England, and at Forton Gaol, outside Portsmouth. Usually they fared reasonably well, although forty days in a black hole, with half-rations and no resting-place but the damp stones, seems a severe penalty for attempting to escape, or for commenting unfavorably on the quality of the meat.27 Isolated cases of barbarity were condemned in London newspapers, and the frequent visits of Mr. Hartley, M.P., and Rev. Thomas Wren, of Portsmouth, to American prisoners, kept punishment within proper bounds. The people of London in December, 1777, subscribed £3,815 17s. 6d. to provide clothing and other necessities. A weekly allowance of two shillings from the American envoys was invaluable so long as it could be maintained, but in 1778 this was unavoidably reduced. The fare occasioned comparatively little protest, although Franklin, in his letters, complains that those who were not sold into service under the African or East India Companies were cheated by public prison contractors.28 In 1780 he provided sixpence per week for each of the four hundred or more Americans, and as his countrymen were not permitted an equal allowance with the French and Spanish prisoners (being rebels), the money was very welcome. In the following year English generals sent home great numbers of captives; and Franklin’s efforts to effect an exchange were thwarted by the caprice of British officials.

Many remained captive in England for as long a period as four years, and when the general act for an exchange was passed, in the winter of 1782, there were more than a thousand Americans held for high treason in England and Ireland.29

The prisoners in some cases were allowed to make trinkets, which they sold to visitors, and they occasionally succeeded in sending letters to their friends. The news which was allowed to filter in was usually bad news, such as the final defeat of the Continentals, or the death of Washington.

In considering the British treatment of American prisoners in America some allowances must be made. The British army managed to cling to the sea-coast of the continent, but could not provide a suitable place in which to confine able-bodied captives who were ready at any time to effect an escape or to co-operate with an attempt made by the rebels to rescue them. The length of the war, also, bore hard upon the British soldiers, three thousand miles from home, and increased an irritation which perhaps received its first impulse from the regular’s natural contempt for the volunteer in rebellion against the King.

There were two ways of relief open to the prisoner in British hands, one at the sacrifice of his honor, another by the injury of his own cause: he could enlist under the crown, stifle his conscience, and take his chance of capture as a deserter; or he could – if fortunate – be exchanged for the redcoat in an American prison. Few of the better soldiers of native birth were willing thus to obtain freedom by service under the King; and the exchange of privates for privates operated so strongly to the advantage of the British forces that conference after conference could find no mutually satisfactory basis of agreement, and the prison-ships kept their burden. These prisoners, who had all the claims of humanity upon their side, were for the most part too enfeebled to be fit for further service, and some were levies called into the field for short periods. When exchanged, therefore, the sick would have to be discharged by Washington, and many of the able-bodied men, having reached the end of their terms of enlistment, would go home. The British captives, on the other hand, were better nourished, and less subject to disease; as they were in the regular army, they would remain in America, or be sent to do garrison duty in the place of troops that were being trained for service in the Colonies.30 So it happened in this way that when Congress was hard pressed to keep in the field a force not too conspicuously inferior to the enemy, an exchange of prisoners was clearly a misfortune. for every reason except that of humanity. As an exchange was a most practical means of “giving comfort to the enemy,” the privates who endured year after year the hardships of prison and prison-ship, instead of going free, were serving their country as truly as if they had been in the field.

Footnotes

- Colonel William Henshaw’s Orderly Book, p. 75.

- Washington’s Orderly Book, May 26, 1778; Orderly Book of the Northern Army at Ticonderoga, p. 126,

- American Archives V., vol. 3, col. 1031.

- E. Elmer’s Journal; in New Jersey Historical Society Proceedings, vol. 3 (1849), p. 93.

- Robbins’s Journal, p. 39.

- Orderly Book of the Northern Army at Ticonderoga, p. 123.

- American Archives V., vol. 3, col. 1584; Massachusetts Historical Society Proceedings, May, 1894, p. 88.

- G. L. Goodale’s British and Colonial Army Surgeons, p. 10.

- Elijah Fisher’s Journal, p. 5.

- Schuyler to Congress, November 20, 1775; Lossing’s Schuyler (1872), vol. I, p. 466. Dr. Rush held to the view that many New Englanders deserted on account of homesickness. When Gates met Burgoyne’s army the excitement was a strong power that overweighed fear and longing for home, so that desertions for a few weeks almost ceased. (Massachusetts Magazine for 1791, p. 284.)

- Dr. A. Waldo’s Diary; in Historical Magazine, May, 1861, p. 133.

- Charles Cushing, in American Archives V., vol. I, cols. 128-132. See also letter of Council of Massachusetts to Ward, July 9, 1776, ibid., col. 146.

- Pennsylvania Magazine, April, July, 1899, pp. 36, 210.

- Dr. William Smith; in Pennsylvania Magazine, July, 1896, pp. 149, 150.

- Director-General Cochran; in Magazine of American History, September, 1884, p. 249.

- Ibid., p. 257.

- Washington to Congress; in his Writings (Ford), vol. 5, p. 241.

- E. Allen’s Narrative, p. 334.

- American Archives V., vol. 4, col. 1234. See also E. Fisher’s Journal, p. 23.

- Dr. A. Waldo’s Diary; in Historical Magazine, May, 1861, p. 132.

- John Trumbull’s Autobiography (New York, 1841), pp. 34-36.

- American Archives V., vol. 3, col. 1138.

- Pennsylvania Packet, September 4, 1781; in F. Moore’s Diary of the American Revolution, vol. 2.

- Martyrs of the Revolution in the British Prison-Ships in the Wallabout Bay, p. 19.

- Philip Freneau’s Capture of the Ship Aurora (1899), pp. 31-43.

- Franklin’s Works (Bigelow), vol. 7, p. 5.

- Charles Herbert’s journal, edited by Livesey, p. 84.

- Franklin’s Works (Bigelow), vol. 9, pp. 108, 109. See also American Archives V., vol. I, col. 754-756; Timothy Connor’s Journal, edited by W. R. Cutter, in New England Historical and Genealogical Register, July, 1876, p. 345, July, 1878, pp. 280, 284; Gentleman’s Magazine for 1778, p. 43.

- Franklin’s Works (Bigelow), vol. 7, pp. 96, 306, 307, 451.

- Washington’s Writings (Ford), vol. 8, p. 340; vol. 9, p. 445. Officers could be exchanged readily, and Washington at one time showed some anxiety to send back General Burgoyne lest ill-health should carry him off and deprive Congress of an opportunity to obtain in exchange for him 1,040 privates, or their equivalent in officers. – Ibid., vol. 9, p. 219.