Contents

Contents

Quick facts

- Peter Jay, a wealthy trader and merchant, married Mary Van Cortlandt in 1728.

- John Jay, the eighth of ten children (seven of whom survived into adulthood), was born on 12 December 1745 in New York City. But a few months after his birth his family moved to Rye, New York.

- In 1774, Jay married Sarah Van Brugh Livingston (1756 – 1802); she was 18, he was 29.

- He was a delegate to the Second Continental Congress in 1775 and 1776, but, due to absence, was not a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

- He became president of the Continental Congress for a term (10-Dec-1778 to 28-Sep-1779).

- He was one of four (including Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Henry Laurens) who negotiated the peace treaty with Great Britain.

- Though not present at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Jay joined James Madison and Alexander Hamilton to promote its ratification by contributing to The Federalist Papers (1787 – 88).

- Due to illness, he was only able to write four of the 85 essays.

- President Washington appointed Jay the first Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court (26-Sep-1789 to 29-Jun-1795).

- As Chief Justice, Jay set the precedent that the Court does not endorse pending legislation; it only rules on the constitutionality of cases heard before it.

- During the nearly six years that Jay presided, the Court heard just four cases.

- While still Chief Justice, Jay negotiated what became the “Jay Treaty” (1795) — which forestalled a second war with Great Britain for nearly 17 years.

- The Jay Treaty was written by Hamilton, who was Secretary of the Treasury.

- Jay was elected the second Governor of New York State and served two terms (1-Jul-1795 to 30-Jun-1801).

- He retired from public life in 1801. President John Adams tried to appoint him to the Supreme Court again that year, but Jay declined.

- Died: 17 May 1829 in Bedford, New York.

Introduction

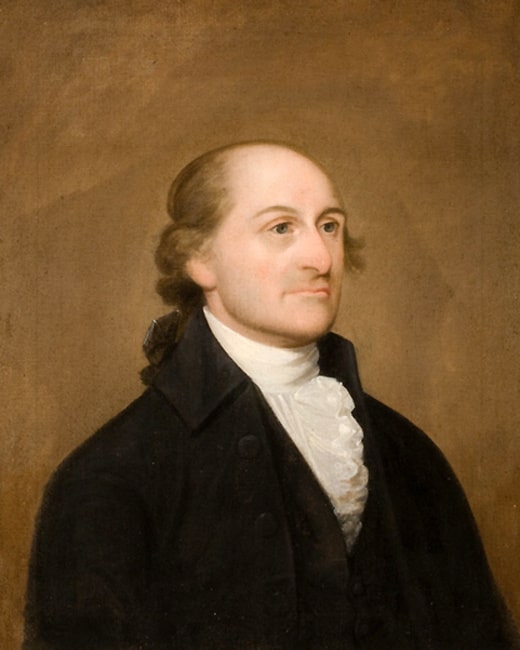

John Jay was an American statesman, diplomat, and first Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. The son of Peter Jay, a descendant of a Huguenot family and a successful New York merchant, he was born in New York City in 1745. Graduating from King’s College (now Columbia University) in 1764, Jay entered the office of Benjamin Kissam, an eminent New York lawyer. He was admitted to the bar in 1768 and rapidly acquired a lucrative practice. He opened his own law office in 1771.

In 1774 Jay married 18-year-old Sarah Van Brugh Livingston, whose father, William Livingston, would become the first governor of New Jersey two years later. Jay thus became connected to one of the most prominent families in New York. He became involved with politics, identifying with the conservative element in the Whig — patriot

— party.

Continental Congress, offices in New York

He became a delegate from New York to the First Continental Congress at Philadelphia in September 1774. One of the youngest members, he was nevertheless entrusted with drawing up an address to the people of Great Britain. He was also a member of the Second Continental Congress, which began meeting on 10 May 1775. Among other duties he prepared an address to the people of Canada and an address to the people of Jamaica and Ireland. In April 1776, while still retaining his seat in the Continental Congress, Jay was chosen as a member of the Third Provincial Congress of New York. Consequently his absence from Continental Congress deprived him of the honor of affixing his signature to the Declaration of Independence.

In 1777 he was chairman of the Committee of the Convention which drafted the first New York State Constitution. After acting for some time as one of the Council of Safety (which administered the state government until the new constitution came into effect), in September 1777 he was made Chief Justice of New York.

A clause in the state constitution prohibited any justice of the State Supreme Court from holding any other post save that of delegate to Congress on a special occasion.

However, in November 1778 the legislature pronounced the secession of what is now the state of Vermont from the jurisdiction of New Hampshire and New York to be such an occasion. It sent Jay to Continental Congress charged with the duty of securing a settlement of the territorial claims for his state. Three days after taking his seat, he was elected President of Congress on 10 December, succeeding Henry Laurens.

Minister plenipotentiary to Spain

On 27 September 1779 Jay was appointed Minister Plenipotentiary to negotiate a treaty between Spain and the United States. He was instructed to try to bring Spain into the treaty that already existed with France, by a guarantee that Spain should have the Floridas — while reserving to the U.S. the free navigation of the Mississippi — in the event that independence would be a success. He was also to solicit a subsidy in consideration of that guarantee, as well as rquest a loan for five million dollars.

His task was difficult. Though Spain had joined France in the war against Great Britain, she didn’t want to imperil her own colonial interests by directly encouraging and aiding the United States. To date, she had refused to recognize the former British colonies as an independent power.

Jay landed at Cadiz on 22 January 1780 and was told that he would not be received in a formal diplomatic capacity. And in the months that followed it became clear that the court was employing a tactic of delay. In May a minister to King Charles III, Count de Florida Blanca, intimated to him that the one obstacle to a treaty was the question of the free navigation of the Mississippi. But when Congress in February 1781 instructed Jay that he might make concessions regarding the navigation of the river, further delays were interposed. With the Americans winning a decisive victory at Yorktown (October 1781), however, Jay realized that signing a treaty at such a cost was no longer advisable or necessary.

His efforts to procure a loan were not much more successful. He was embarrassed by Congress in drawing bills upon him for large sums. By importuning the Spanish minister and by pledging his personal responsibility, Jay was able to meet some of the bills, but not others. Ultimately, only a timely subsidy from France saved the credit of the United States.

Negotiating peace with Britain

In 1781 Jay was commissioned to act with Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Henry Laurens in negotiating a peace with Great Britain. He arrived in Paris on 23 June 1782, and jointly with Franklin had proceeded far with the negotiations when Adams arrived late in October. The instructions of the American negotiators were as follows:

You are to make the most candid and confidential communications upon all subjects to the ministers of our generous ally, the king of France; to undertake nothing in the negotiations for peace or truce without their knowledge and concurrence; and ultimately to govern yourselves by their advice and opinion, endeavoring in your whole conduct to make them sensible how much we rely on his majesty’s influence for effectual support in every thing that may be necessary to the present security, or future prosperity, of the United States of America.

Jay, however, in a letter written to the president of Congress from Spain, had expressed in strong terms his disapproval of such dependence upon France. So on arriving in Paris he demanded that Great Britain should treat with his country on an equal footing by first recognizing its independence — despite the counsel of the French minister, comte de Vergennes, who contended that an acknowledgment of independence as an effect of the treaty was as much as could reasonably be expected. Finally, owing largely to Jay, who suspected the good faith of France, the American negotiators decided to deal separately with Great Britain.

The provisional articles — so favorable to the United States and of great surprise to the courts of France and Spain — were signed on the 30 November 1782. Nine months later, on 3 September 1783 the Treaty of Paris was adopted with no significant changes to the articles.

Jay returned to the United States and landed at New York on 24 July 1784, seeing firsthand the now-freed city that the British had held for seven years and recently evacuated. Two and a half months earlier, on 7 May, Congress had chosen Jay to be secretary for foreign affairs; in December he resigned his seat in Congress and accepted the office. He continued in that capacity until 1790 when Thomas Jefferson became Secretary of State in the Washington administration.

Chief Justice of the Supreme Court

Jay had taken a keen interest in the new Constitution. As an advocate for its ratification he contributed — along with James Madison and Alexander Hamilton — to the series later known as the Federalist Papers. He wrote four early essays (Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5) and then fell ill, finally writing just one more (No. 64). He anonymously published a vindication of the Constitution in An Address to the People of New York (though he failed in concealing his authorship); and at the State Convention in Poughkeepsie he ably seconded Hamilton in securing its ratification by New York (26 July 1788).

In making his first appointments to federal offices President Washington asked Jay to become Secretary of State, which he declined. Then Washington asked Jay to choose his position; subsequently Jay became Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. He was confirmed by the Senate and began the position in September 1789, serving until June 1795.

The most famous case that came before him was that of Chisolm v. Georgia (1793), in which the question was whether a state could be sued by a citizen of another state. Georgia argued that it could not be so sued, on the ground that it was a sovereign state, but Jay decided against Georgia, on the ground that sovereignty in America resided with the people. This decision led to the adoption of the 11th amendment to the federal constitution (effective February 1795), which provides that no suit may be brought in the federal courts against any state by a citizen of another state or by a citizen or subject of any foreign state.

Despite being Chief Justice, Jay consented to stand for the governorship of New York State in 1792. A partisan returning-board found the returns of three counties technically defective, and though Jay had received an actual majority of votes, his opponent, George Clinton, was declared elected.

Jay’s Treaty with Britain

In 1794 Washington appointed Jay Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Great Britain, charged with negotiating a new treaty with the former mother country.

Ever since the end of the Revolutionary War there had been continued friction between the United States and Great Britain. The British refused to withdraw its troops from the forts on the northwestern frontier, as was required by the Treaty of Paris; she refused to pay compensation for slaves carried away by the British army at the close of the War; and Britain restricted American commerce and refused to enter into any commercial treaty with its former colony.

After war broke out between France and Great Britain in 1793, there were added grievances. These included the anti-neutral naval policy, according to which British naval vessels were authorized to search American merchantmen and impress American seamen, provisions were treated as contraband of war, and American vessels were seized for no other reason than that they had on board goods which were the property of the enemy or were bound for a port which, though not actually blockaded, was declared to be blockaded. The anti-British feeling in the House of Representatives became so strong that on 7 April 1794 a resolution was introduced to prohibit commercial intercourse between the United States and Great Britain until the northwestern posts should be evacuated and Britain’s anti-neutral naval policy should be abandoned.

Washington feared another war; hence his appointment of Jay, which the Senate confirmed on 19 April.

Jay landed at Falmouth in June 1794, signed a treaty with Lord Grenville on the 19 November, and returned to New York on the 28 May 1795.

The treaty, known to history as the Jay Treaty or Jay’s Treaty, provided that the northwestern posts should be evacuated by 1 June 1796; that commissioners should be appointed to settle the northeast and the northwest boundaries; and that the British claims for British debts as well as the American claims for compensation for illegal seizures be referred to commissioners. More than one-half of the clauses in the treaty related to commerce, and though they contained only small concessions to the United States, they were about as much as could reasonably be expected under the circumstances.

One clause, the operation of which was limited to two years from the close of the existing war, provided that American vessels not exceeding 70 tons burden might trade with the West Indies, but should carry only American products there and take away to American ports only West Indian products. Moreover, the United States was to export in American vessels no molasses, sugar, coffee, cocoa, or cotton to any part of the world. Jay consented to this prohibition under the impression that the articles named were peculiarly the products of the West Indies, not being aware that cotton was rapidly becoming an important export from the southern states. The operation of the other commercial clauses was limited to twelve years. By them the United States was granted limited privileges of trade with the British East Indies; some provisions were made for reciprocal freedom of trade between the United States and the British dominions in Europe; some articles were specified under the head of contraband of war

; it was agreed that whenever provisions were seized as contraband they should be paid for, and that in cases of the capture of a vessel carrying contraband goods such goods only and not the whole cargo should be seized; it was also agreed that no vessel should be seized merely because it was bound for a blockaded port, unless it attempted to enter the port after receiving notice of the blockade.

The treaty was laid before the Senate on the 8 June 1795, and, with the exception of the clause relating to trade with the West Indies, was ratified on the 24th by a vote of 20 to ten. Since the Senate had enjoined secrecy on its members — even after the treaty had been ratified — the public was ignorant of its contents. But days after ratification, Senator George Mason of Virginia gave out a copy for publication.

The Republican party, sympathizing with France and disliking Great Britain, had been opposed to Jay’s mission from the beginning and had denounced Jay as a traitor, guillotining him in effigy when they heard that he was actually negotiating. The publication of the treaty only heightened their fury. They filled newspapers with articles denouncing it, wrote virulent pamphlets against it, and burned Jay in effigy. The British flag was insulted. Hamilton was stoned at a public meeting in New York while speaking in defense of the treaty and Washington was grossly abused for signing it. In the House of Representatives the Republicans endeavored to prevent the execution of the treaty by refusing the necessary appropriations, and a vote (on 29 April 1795) on a resolution that it ought to be carried into effect stood 49 to 49; but on the next day the opposition was defeated by a vote of 51 to 48. Once in operation the treaty slowly grew in favor.

Two days before landing on his return from the English mission, Jay had been elected Governor of New York. Three years later, notwithstanding his unpopularity nationally, he was re-elected in 1778 to a another term.

Retirement

With the close of his second term, Jay ended his public career. Not yet 57 years old, he refused all offers of office and retired to his country estate near Bedford, New York. There he spent the rest of his life in rarely interrupted seclusion, though from 1821 until 1828 he was president of the American Bible Society.

Among the most important of the Founding Fathers, Jay’s life was one of integrity, his contributions integral to the birth of the American republic. In politics he inclined toward conservatism. After the rise of political parties he stood with Alexander Hamilton and John Adams as one of the foremost leaders of the Federalist party.

Jay died in May 1829 at his home in Bedford. He was 83.