Contents

Contents

Quick facts

- Born: 3 July 1738 in Boston, Massachusetts.

- Copley was the first native-born American artist to paint miniatures. Between 1755 and the early 1770s, he produced 37 of them.

- Seeking the “best Swiss crayons” to create pastel portraits, Copley wrote (1762):

You may perhaps be surprised that so remote a corner of the Globe as New England should have any d[e]mand for the necessary utensils for practicing the fine Arts, but I assure You Sir however feeble our efforts may be, it is not for want of inclination that they are not better, but the want of opportunity to improve ourselves…

- By 1774 Copley created at least 58 pastels — though it seems he never did another after leaving America.

- While in New York for 7 months (1771), Copley painted at least 37 oil portraits — a copious five to six a month, on average. However, with the outbreak of the Revolution (1775), most of these vanished as the (mostly) Loyalist owners fled the country.

- Of the approximately 350 portraits Copley painted before he left America, 312 exist today.

- Died: 9 September 1815 in London, England.

- Buried in Croydon, Surrey, England.

Did you know?

Later called America’s first art gallery,

the Boston studio of John Smibert (1688 – 1751) displayed casts and copies of Old Masters that the artist had produced while in Europe. Sitting above the art supplies and prints shop Smibert opened in 1734, his studio provided a valuable early education to not only John Singleton Copley, but also Charles Willson Peale, Gilbert Stuart, and other artists.

Introduction

John Singleton Copley, inarguably the greatest and most successful of the American colonial painters, was born of Irish parents in 1738, at Boston, Massachusetts. Naturally talented, a hard worker, a striver — he was about ten when his father died. His mother, Mary Singleton Copley, married Peter Pelham in 1748.

For young Copley, who had precociously exhibited artistic talent since an early age, the association with Pelham was brief but fortunate. Pelham was a teacher. Whatever education Copley had had previously, he now learned reading, writing, and arithmetic in the school that Pelham conducted out of his home. Also, Pelham was a London-trained engraver. He taught his step-son the art of engraving and connected him to other artists. In addition, Copley now studied the art of English portraitists and European old masters in a trove of prints kept by his step-grandfather.

Pelham died in 1751 — leaving Copley without a mentor (and his mother a widow once again). Yet there were other influencers.

Influences

John Smibert, a Scottish artist who settled in Boston in 1830, had a shop that sold paints, artist supplies, and prints. Even more important for Copley, he displayed copies of the old masters that he had painted while in Europe. Smibert (d. 1751) was very near the end of his career while Copley was just beginning his. So the young artist borrowed where he could: the influence of Smibert’s late 17th-century baroque style is visible in Copley’s early portraits.

A more lasting influence was that of English portrait painter Joseph Blackburn (active in Boston c. 1750 – 65), who brought the mid-18th century rococo style to Boston. Taking a cue from Blackburn, Copley worked toward a style of graceful poses, costumes and jewelry, loose hair, and gorgeous textiles. It became the style that pleased his wealthy merchant-class clientele. As he matured, he was able to seemingly penetrate and reveal the characters of his sitters — in a way that reinforced their own conception of themselves.

The Boston Artist

By the 1760s Copley was famous in Boston and throughout the American colonies. Having mastered oils, he next learned to create portraits with pastels — a very popular medium at the time — and became one of its great practitioners.

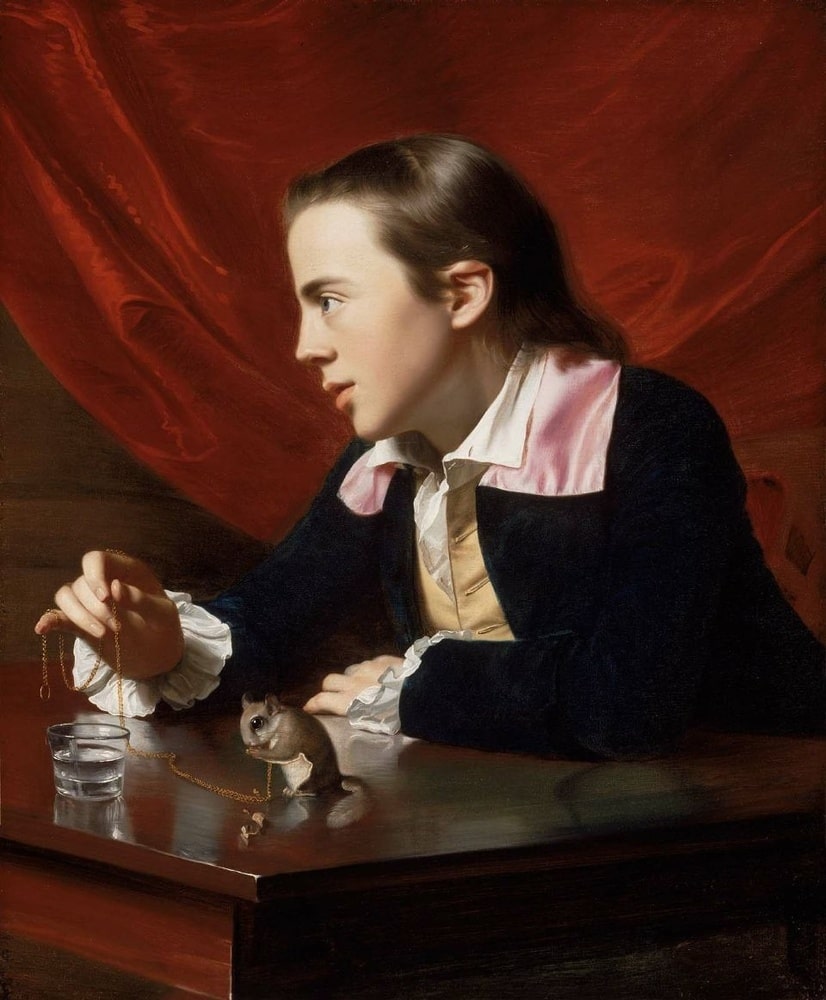

In spring 1766, A Boy with a Flying Squirrel — Copley’s portrait of his half-brother, Henry Pelham — was included in the London exhibition of the Incorporated Society of Artists. Winning praise from Joshua Reynolds and Benjamin West, it was the beginning of his reputation in England, and it earned him election to the Society.

Despite encouragement from both West and Reynolds to go to London to improve his craft, Copley, having as much work as he could handle — and also earning very good money — remained in Boston. He created images of Samuel Adams and Paul Revere (among his very best paintings). He painted revolutionaries John Hancock and Joseph Warren, as well as commander-in-chief of the North American British Army, General Thomas Gage and his wife. While doing so, Copley achieved a level of success that gave him social status and a lifestyle comparable to his patrons. He married the daughter of one of Boston’s richest merchants, Susanna Farnham Clarke in 1769, and they moved into a house on Beacon Hill, not far from Hancock and other wealthy merchants. (The marriage, lasting 45 years, produced six children.)

Except for a seven month stint in New York in 1771, Copley worked exclusively in Boston. However, as conflict with Britain intensified — and especially after the Boston Tea Party (16-Dec-1773), where the tea consigned to his father-in-law was dumped into the harbor, bringing him to the brink of bankruptcy — Copley’s position there became increasingly difficult. His wife’s family were all Loyalists. And while he tried to stay neutral, his commissions shriveled. So on 10 June 1774 he sailed for England, without his family, intending to return to Boston after tensions with Britain ceased.

Europe and England

Almost immediately Copley traveled to Paris, then to Italy, studying and painting. After seven months in Rome, where he completed his immense (7 foot-wide) painting of Mr. and Mrs. Ralph Izard, he returned to London. There in July 1775 — participating in the exodus of Loyalists who fled Boston after the British were forced to evacuate in March — he found his wife and children waiting for him.

In London, Copley began a successful portrait studio, and, as his reputation widened, he earned commissions from British aristocrats and royalty. At the same time he began to put his creative energies into history paintings, a genre popularized by West. In 1778 he had his first major success with Watson and the Shark, which he displayed at the Royal Academy.

He followed up with The Death of the Earl of Chatham (1783), to even greater critical and popular acclaim, which secured his reputation as an historical painter. Unusually, he chose not to exhibit his painting at the Royal Academy, but in separate quarters, charging an admission fee — to the consternation of his fellow Academy members. Yet, during the ten weeks that the painting was displayed some 20,000 people saw it. Having been made an Associate of the Royal Academy in 1777, he was now made an Academician.

Copley was 62. Although he hoped to repeat the success and popularity of Watson

and The Death of Chatham,

he never did. In 1790, his Defeat of the Floating Batteries at Gibraltar drew enormous crowds but the critical response was lukewarm. His portrait commissions dwindled. When Joshua Reynolds died in 1792, Copley had hoped he would be elected president of the Academy; instead Academicians voted for his compatriot, Benjamin West. Openly disagreeing with West on most Academy issues he lost many of his friends.

In his last 15 years Copley produced few notable artworks, suffered bouts of depression, and increasingly needed money. At age 77, 1815, Copley died of a stroke in his London home. Twelve years later, his son, John, was appointed Lord Chancellor and elevated to the peerage as 1st Baron Lyndhurst.