Contents

Contents

The first in order visited was SAMUEL DOWNING, and the sketch of his life shall introduce the series.

Mr. Downing lives in the town of Edinburgh, Saratoga County; New York. His age is one hundred and two years. To reach his home, you proceed to Saratoga, and thence by stage some twenty miles to the village of Luzerne, on the upper Hudson. Here you are at once rewarded for your journey thus far. Few spots more beautiful are to be found. The river, flowing above it broad and free, at this point is compressed within a narrow gorge some twelve or fifteen feet in width, through which, after passing over a series of rapids known as Rockwell’s Falls, it rushes with great rapidity and force, the sound of its waters filling the air with music and your heart with freshness, as you listen to them, ceaseless, by day or by night. Around the village tower the mountains of the region, southern spurs of the Adirondacks; one, a solitary, lofty dome, a landmark far and wide. But the gem of the village seemed to me its lake. This lies a little out of and above it, and for completeness and exquisiteness of beauty is not unworthy the vicinity of Lake George, from the head of which, connected with it by a series of lesser lakes, it is distant but twelve miles. I viewed it by moonlight on the evening of my arrival. The night was still, and the smoky haze that brooded over all the region subdued and softened the outlines of the mountain masses which are its setting. And there, in their mingled shadow and the moonlight, lay the lake, the forests fringing it to its very edge, its shores winding in and out among them, a beautiful wooded island rising from its centre, with the dip of oars and the voices of singers from parties of evening voyagers coming sweetly to the land, together forming a scene which for soft and dreamlike effect seemed more befitting the style of Italy than the stern and rugged, scenery of our northern America. Add to this the attraction of a pleasant hotel within near sight and sound of the river rapids, with one of the cheeriest and most obliging of landlords, and it is not strange that Luzerne should be adopted, as it is, as a place of summer resort by many families of wealth and leisure from the cities below.

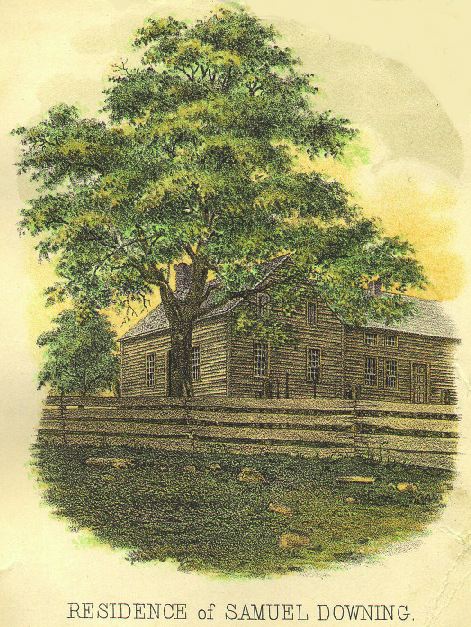

From Luzerne the home of Mr. Downing is distant some twenty-five miles: up the valley of the Sacandaga River, and for it I set out early on the following morning. The Sacandaga is a branch of the Hudson, putting into it from the west just below Luzerne. Its valley is narrow and walled in on both sides by high mountains; those on the southern side, known as the Kayderasseras (the title of an early patent) or Greenfield Mountains, separating it from the valley of the Mohawk. It was through this valley that Sir John Johnson, in 1780, made his incursion from Canada by way of Crown Point into the Mohawk Valley, and by the head of it and the Indian paths west of the Adirondack Mountains that he returned. Near the head of the valley the river makes a broad bend to the southwest round a point of hills, coming up on their western side to Lake Pleasant, its source. At the head of this bend, about midway between the lake and the river, upon the summit of the intervening highlands, stands the house of Mr. Downing, built by himself, the first framed house in the town of Edinburgh, seventy years ago. It was about noon when I reached there; and as I drove up I observed on the eastern side of the house, near the front corner of it, (the corner nearest you in the picture,) seated between two bee-hives, bending over, leaning upon his cane and looking on the ground, an old man, whom I at once concluded to be the object of my search. Indeed, once in the vicinity you have no difficulty in finding him, as all in the region know “Old Father Downing,” and speak of him with respect and affection. The celebration of his one-hundredth birthday, to which the whole country around gathered, served to make him acquainted, with many who might otherwise, in the seclusion of his age, have lost sight of him. On entering the yard l at once recognized him from his photograph, and addressing myself to him, said, “Well, Mr. Downing, you and the bees seem very good friends.” (There was barely room for him between the two hives, and the swarms were working busily on both sides of him.) “Yes,” he replied, “they don’t hurt me and I don’t hurt them.”

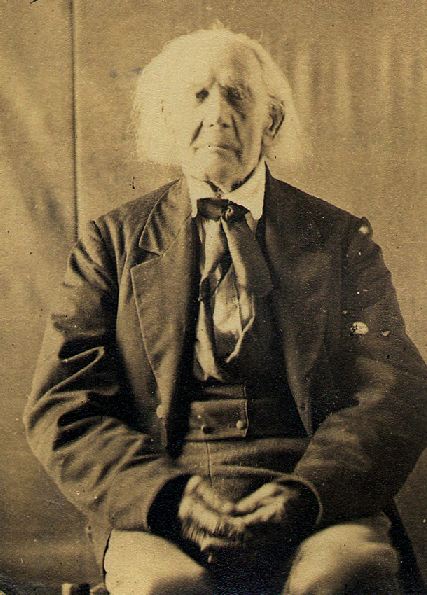

On telling him that I had come a long way to see an old soldier of the Revolution, he invited me to walk into the house, himself leading the way. The day was extremely warm. I inquired of him which suited him best, warm weather or cold. “If I had my way about it”‘ he answered, “I should like it about so. But we can’t do that: we have to take it as it comes.” The day before had been one of the hottest of the season, so, much so that coming up by stage from Saratoga, we could scarcely endure the journey. Yet in the middle of it, the old man, they told me, walked some. two miles and a half over a very tedious road to the shoemaker’s, got his boots tapped, and walked home again. Mr. Downing is altogether the most vigorous in body and mind of the survivors. Indeed, judging from his bearing and conversation, you would not take him to be over seventy years of age. His eye is indeed dim, but all his other faculties are unimpaired, and his natural force is not at all abated. Still he is strong, hearty, enthusiastic, cheery: the most sociable of men and the very best of company. He eats his full meal, rests well at night, labors upon the farm, “hoes corn and potatoes, and works just as well as anybody.” His voice is strong and clear, his mind unclouded, and he seems, as one of his. neighbors said of him, “as good for ten years longer as he ever was.” Seated in the house, and my errand made known to him, he entered upon the story of his life, which I will give as nearly as possible in the old man’s own words.

“I was born said he, “in the town, of Newburyport, Mass., on the 31st of November, 1761. One day, when I was a small boy, my parents, went across the bay in a sailboat to a. place called Joppa. They left me at home; and I went out into the street to play marbles with the boys. As we were playing, a man came along and asked if we knew of any boy who would like to go and learn the trade of spinning-wheel making. Nobody answered; so I spoke up, and said, ‘Yes, I want to go.’ ‘Where are your parents?’ asked he. ‘They aint at home,’ said I; ‘but that wont make no odds; I will go.’ So he told me that if I would meet him that afternoon at Greenleaf’s tavern, (I remember the tavern keeper’s name,) he would take me. So I did. They asked me at the tavern where I was going. I told them I was going off. So we started; he carried me to Haverhill, and the next day to Londonderry, where we stayed over Sunday. It was the fall of the year. I remember the fruit was on the ground, and I went out and gathered it. I was happy yet. From Londonderry he carried me to Antrim, where he lived. His name was Thomas Aiken. Antrim was a wooded country then. When I got there I was homesick; so I went into the woods and sat down on a hemlock log, and cried it out. I was sorry enough I had come. When I went back to the house they accused me of it; but I denied it. I staid with Mr. Aiken till after the breaking out of the war, working at wheels during the day and splitting out spokes at night. I had lived with him so six years. He didn’t do by me as he agreed to. He agreed to give me so much education, and at the end of my time an outfit of clothes, or the like, and a kit of tools. So I tells aunt, (I used to call Mr. Aiken uncle an his wife aunt,) ‘Aunty, Uncle don’t do by me. as he agreed to. He agreed to send me to school, and he hasn’t sent me a day;’ and I threatened to run away. She told if I did they’d handcuff me and give me a whipping. ‘But,’ said I, ‘You’ll catch me first, won’t you, Aunty?’ ‘O,’ she said, ‘they’d advertise me.”

“Well, the war broke out. Mr. Aiken was a militia captain; and they used to be in his shop talking about it. I had ears, and I had eyes in them days. They was enlisting three years men and for-the-war men. I heard say that Hopkinton was the enlisting place. One day aunt said she was going a-visiting. So I said to myself, ‘That’s right, Aunty; you go, and I’ll go too.’ So they went out, and I waited till dinner time, when I thought nobody would see me, and then I started. I had a few coppers, but I darsn’t lake any of my clothes, for fear they’d have me up for a thief. It was eighteen miles, and I went it pretty quick. The recruiting officer, when I told him what I’d come for, said I was too small. I told him just what I’d done. ‘Well,’ said he, ‘you stay here and I’ll give you a letter to Col. Fifield over in Charlestown and perhaps he’ll take you.’ So, I stayed with him; and when uncle. and aunt came home that night they had no Sam. The next day I went and carried the letter to Col. Fifield, and he accepted me. But he wasn’t quite ready to go: he had his haying to do; so l stayed with him and helped him through it, and then I started for the war. Uncle spent six weeks in looking for me, but he didn’t find me.”

“But did your parents hear nothing of you all this time?”

“Yes Mr. Aiken wrote to them about a year after he stole me. They had advertised me and searched for me, but at last concluded I had fallen off the dock and been drowned.

“The first duty I ever did was to guard wagons, from Exeter to Springfield. We played the British a trick; I can remember what I said as well as can be. We all started off on a run, and as I couldn’t see anything, I said, ‘I don’t see what the devil we’re running after or running away from; for I can’t see anything.’ One of the officers behind me said, ‘Run, you little dog, or I’ll spontoon you.’ ‘Well’ I answered, ‘I guess I can run as fast as you can and as far.’ Pretty soon I found they were going to surprise a British train. We captured it; and among the stores were some hogsheads of rum. So when we got back to camp that night the officers had a great time drinking and gambling; but none for the poor soldiers. Says one of the sergeants to me, ‘We’ll have some of that rum.’ It fell to my lot to be on sentry that night; so I couldn’t let ’em in at the door. But they waited till the officers got boozy; then they went in at the windows and drew a pailful, and brought it out and we filled our canteens, and then they went in and drew another. So we had some of the rum; all we wanted was to live with the officers, not any better.

Afterwards we were stationed in the Mohawk Valley. Arnold was our fighting general, and a bloody fellow he was. He didn’t care for nothing; he’d ride right in. It was ‘Come on, boys!’ ’twasn’t ‘Go, boys!’ He was as brave a man as ever lived. He was dark-skinned, with black hair, of middling height. There wasn’t any waste timber in him. He was a stern looking man, but kind to his soldiers. They didn’t treat him right: he ought to have had Burgoyne’s sword. But he ought to have been true. We had true men then; twasn’t as it is now. Everybody was true: the tories we’d killed or driven to Canada.”

“You don’t believe; then, in letting men stay at their homes and help the enemy?”

“Not by a grand sight!” was his emphatic reply, “The men that caught Andre were true. He wanted to get away, offered them everything. Washington hated to hang him; he cried, they said.”

The student of American history will remember the important part which Arnold performed in the battle connected with the surrender of Burgoyne. Mr. Downing was engaged.

“We heard,” he said, “Burgoyne was coming. The tories began to feel triumphant. One of them came in one morning and said to his wife, “Ty (Ticonderoga) is taken, my dear.’ But they soon changed their tune. The first day at Bemis Heights both claimed the victory. But by and by we got Burgoyne where we wanted him, and he gave up. He saw there was no use in fighting it out. There’s where I call ’em gentlemen. Bless your body, we had gentlemen to fight with in those days. When they was whipped they gave up. It isn’t so now.

“Gates was an ‘old granny’ looking fellow. When Burgoyne came up to surrender his sword, he said to Gates, ‘Are you a general? You look more like a granny than you do like a general.” ‘I be a granny,’ said Gates, ‘and I’ve delivered you of ten thousand men today.’

“Once, in the Mohawk Valley, we stopped in William Johnson’s great house. It would hold a regiment. Old Johnson appeared to us: I don’t know as you’ll believe it. The rest had been out foraging. One had stolen a hive of honey; some others had brought in eight-quarters of good mutton, and others, apples and garden sauce, and so forth. Ellis and I went out to get a sack of potatoes, some three pecks. When we got back to Johnson’s, as we were going through the hall, I looked back, and there was a man. I can see now just how he looked. He had on a short coat. What to do with the potatoes we didn’t know. It wouldn’t do to carry them into the house; so I ran down cellar. When the man got to the middle of the hall, all at once he disappeared. I could see him as plain – O, if I could see you as plain!

” By and by they began to talk about going to take New York. There’s always policy, you know, in war. We made the British think we were coming to take the city. We drew up in line of battle: the British drew up over there, (pointing with his hand.) They looked very handsome. But Washington went south to Yorktown. La Fayette laid down the white sticks, and we threw up entrenchments by them. We were right opposite Washington’s headquarters. I saw him every day.”

“Was he as fine a looking man as he is reported to have been?”.

“Oh!” he exclaimed, lifting up both his hands and pausing, “but you never got a smile out of him. He was a nice man. We loved him. They’d sell their lives for him.” I asked, “What do you think he would say if he was here now?”

“Say!” exclaimed he, “I don’t know, but he’d be mad to see me sitting here. I tell ’em if they’ll give me a horse I’ll go as it is. If the rebels come here, I shall startingly take my gun. I can see best furtherest off.”

“How would Washington treat traitors if he caught them?”

“Hang ’em to the first tree!” was his reply.

He denounces the present rebellion, and says he only wishes to live to see it crushed out. His father and his wife’s father were in the French War. His brother was out through the whole war of the Revolution. He has a grandson now in the army, an officer in the Department of the Gulf, – a noble looking young man, as represented by his photograph. He has been in the service from the beginning of the war.

‘”When peace was declared,” said the old man, concluding his story of the war, “we burnt thirteen candles in every hut, one for each State.”

I have given his narrative in his own words, because to me, as I listened, there was an unequaled charm in the story of the Revolution, broken and imperfect though it was, from the lips of one who was a living actor in it. The very quaintness and homeliness of his speech but added to the impression of reality and genuineness. I felt as I listened to him that the story which he told was true.

At the close of the war, Mr. Downing returned to Antrim, “too big,” as he said, “for Aunty to whip.” Soon after his return, he married Eunice George, aged eighteen years. She died eleven years ago. By her he had thirteen children. Three of these are now living. The one with whom he resides is his youngest son, and, though himself seventy-three years old, his father addresses him still as “Bub.” He came from Antrim to Edinburgh in 1794, “And to show you,” said he, “that there was one place I didn’t run away from, I will give you this,” handing me the following certificate

TO ALL WHOM IT MAY CONCERN.

This may certify that the bearer, Samuel Downing, with his wife, have been good members of society; has received the ordinance of baptism for their children in our church; and is recommended to any church or society, where Providence is pleased to fix them, as persons of good moral character. Done in behalf of the Session.

ISAAC COSHRAN, Session Clerk.

Antrim, Feb. 27, 1794.

“It must have been a pretty wild country when you came here?”

“O, there wasn’t a marked tree; it was all a wilderness.”

“How came you to come?”

They said in Antrim we could live on three days’ work here as easy as we could on six there. So we formed a company to come. There were some twenty, but I was the only one that came. I sold my farm there, one hundred and ten acres, for a trifle; and my brother and I came out here to look. As soon as we got here and saw the country I said to my brother, ‘I’ve given my farm away, and have nothing to buy another with: so I’ve got to stay here. But you’ve sold well: so you go right back and buy another.” All the land round here was owned by old Domine Gross. I took mine of a Mr. Foster; and when I’d chopped ten acres and cleared it and fenced it, I found my title wasn’t good: that Mr. Foster hadn’t fulfilled the conditions on which he had it of Mr. Gross. So we went down together to see the Domine about it. I told him I’d paid for the land. ‘No matter,’ said he, ‘it isn’t yours.’ ‘But,’ said I, ‘Mr. Gross, I’ve chopped ten acres and cleared it and fenced it; aint I to have anything for my labor?’ ‘I don’t thank you’,’ he replied, ‘for cutting my timber.’ Then I began to be scared. So says I, ‘Mr. Foster, I guess we’d better be getting along towards home.’ ‘O, you can have the land,’ says the old Domine, ‘only you must give me fifty pounds more; and you can make me a little sugar now and then.’ ‘Well,’ said I, ‘I will go over to your agent and get the papers.’ ‘O, I can do the writing,’ said he. So I paid the money and got the land.”

And on it he has lived and labored for seventy years. Its neighborhood to his old battle-grounds might have had its influence in determining his selection of it for a home.

At the age of one hundred, Mr. Downing had never worn glasses, or used a cane. The fall before, he had pulled, trimmed, and deposited in the cellar, in one day, fifteen bushels of carrots. His one hundredth birthday was celebrated by his neighbors and friends, upon his farm, with a large concourse, estimated at a thousand persons, the firing of one hundred guns, and an address by George S. Batcheller, Esq., of Saratoga. On this occasion the old man cut down a hemlock tree five feet in circumference, and later in the day a wild cherry tree near his house, of half this size. He says he could do it again, and it is likely that he could. The trees were sold upon the ground, and stripped of their branches by those present for canes and other mementoes of the occasion. The stump of the larger one was sawed off and carried to Saratoga by Robert Bevins, of that place. The axe with which the trees were cut was sold for seven dollars and a half.

Mr. Downing lives very comfortably with his son, James M. Downing. His health has always been good. His pension, formerly eighty dollars a year, was increased at the last session of Congress to one hundred and eighty dollars; He pays no particular attention to his diet; drinks tea and coffee, and smokes tobacco. He gets tired sometimes, his son says, during the day; but his sleep at night restores him like a child. It is a curious circumstance that his hair, which until lately has been for many years silvery-white, is now beginning to turn black. In a lock of it, lying before me as I write, there are numerous perfectly black hairs.

By religious persuasion, Mr. Downing is a Methodist. “Why,” said he, “I’ll tell you: because they are opposed to slavery, and believe in a free salvation.”

He is as staunch in his religious belief as he is in his personal character; expounds his faith intelligently and forcibly; believes thoroughly what he believes, and rejects earnestly what he rejects. Among the latter is the doctrine of reprobation, concerning which he tells the story of a controversy which he had with an old Methodist preacher, who held and preached the doctrine.

“‘You believe,’ said he, ‘that God from eternity has elected a part and reprobated a part of mankind ?’

‘Yes,’ replied the preacher, ‘that is my belief.’ ‘Have you wicked children?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Do you pray for them ?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Have you wicked neighbors?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Do you pray for them?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘But how do you know but they are reprobated?’ He didn’t say anything in reply then. A while after I met him, and asked him if he still believed in reprobation. ‘No.’ he answered, ‘I’ve thrown away that foolish notion.”‘

Mr. Downing’s faith in the Invisible is firm and clear, and his anticipation of the rest and reward of Heaven strong and animating. He greatly enjoys religious conversation, invokes a blessing at the table; and when prayer was offered, at his request, responded intelligently and heartily, in true Methodist style. Doubtless, when the earthly house of this tabernacle is dissolved, he will find awaiting him “a building of God, an house not made with hands, eternal in the heavens.”

The sun was drawing low as I left him, to return to Luzerne. My interview with him had been most interesting and delightful. I parted from him with regret. His eyes filled with tears as, in bidding him good-bye, I mentioned that better country where I should hope again to meet him. As I rode away, I turned my eyes southward over the valley of the Mohawk, bounded in the dim distance by the Catskill Mountains. I felt anew how great the change which a hundred years has wrought, which a single lifetime covers. I had just parted from a man still living who had hunted the savage through that I valley now thronged with cities and villages – in place of the then almost unbroken wilderness, now fair fields and pleasant dwellings – in place of constant peril and mortal conflict, now security and peace; and my heart swelled afresh with gratitude to the men who had rescued their land from the tyrant and the savage, and had made it for their children so fair and happy a home.