Contents

Contents

The wife of Benedict Arnold was Margaret Shippen, of Philadelphia. One of her ancestors – Edward Shippen, who was Mayor of the city in the beginning of the eighteenth century, suffered severe persecution from the zealots in authority at Boston for his Quakerism; but, successful in business, amassed a large fortune, and according to tradition, was distinguished for “being the biggest man, having the biggest house, and the biggest carriage in Philadelphia.” His mansion, called “the governor’s house ” – “Shippen’s great house” – and “the famous house and orchard outside the town,” – was built on an eminence, the orchard overlooking the city; yellow pines shaded the rear, a green lawn extended in front, and the view was unobstructed to the Delaware and Jersey shores; – a princely place, indeed, for that day – with its summer-house, and gardens abounding with tulips, roses and lilies! It is said to have been the residence, for a few weeks, of William Penn and his family. An account of the distinguished persons who were guests there at different times would be curious and interesting.

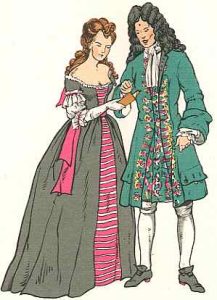

Edward Shippen, afterwards Chief Justice of Pennsylvania, was the father of Margaret. His family, distinguished among the aristocracy of the day, was prominent after the commencement of the contest among those known to cherish loyalist principles – his daughters being educated in these, and having their constant associations and sympathies with those who were opposed to American independence. The youngest of them – only eighteen years of age – beautiful, brilliant and fascinating, full of spirit and gaiety – the toast of the British officers while their army occupied Philadelphia – became the object of Arnold’s admiration. She had been one of the brightest of the belles of the Mischianza; “and it is somewhat curious that the knight who appeared in her honor on that occasion, chose for his device a bay-leaf – with the motto: “Unchangeable.” This gay and volatile young creature, accustomed to the display connected with “the pride of life” – and the homage paid to beauty in high station, was not one to resist the lure of ambition, and was captivated, it is probable, through her girlish fancy, by the splendor of Arnold’s equipments, and his military ostentation. These appear to have had their effect upon her relatives; one of whom, in a manuscript letter still extant, says: “We understand that General Arnold, a fine gentleman, lays close siege to Peggy;” – thus noticing his brilliant and imposing exterior, without a word of information or inquiry as to his character or principles.

A letter from Arnold to Miss Shippen, which has been published – written from the camp at Raritan – February 8th, 1779 – not long before their marriage, shows the discontent and rancor of his heart, in the allusions to the President and Council of Pennsylvania. These feelings were probably expressed freely to her, as it was his pleasure to complain of injury and persecution; while the darker designs, of which no one suspected him till the whole community was startled by the news of his treason, were doubtless buried in his own bosom.

Some writers have taken delight in representing Mrs. Arnold as another Lady Macbeth – an unscrupulous and artful seductress, whose inordinate vanity and ambition were the cause of her husband’s crime; but there seems no foundation even for the supposition that she was acquainted with his purpose of betraying his trust. She was not the being he would have chosen as the sharer of a secret so perilous, nor was the dissimulation attributed to her consistent with her character. Arnold’s marriage, it is true, brought him more continually into familiar association with the enemies of American liberty, and strengthened distrust of him in the minds of those who had seen enough to condemn in his previous conduct; and it is likely that his propensity to extravagance was encouraged by his wife’s taste for luxury and display, while she exerted over him no saving influence. In the words of one of his best biographers: “He had no domestic security for doing right – no fireside guardianship to protect him from the tempter. Rejecting, as we do utterly, the theory that his wife was the instigator of his crime – all common principles of human action being opposed to it – we still believe that there was nothing in her influence or associations to countervail the persuasions to which he ultimately yielded. She was young, gay and frivolous; fond of display and admiration, and used to luxury; she was utterly unfitted for the duties and privations of a poor man’s wife. A loyalist’s daughter, she had been taught to mourn over even the poor pageantry of colonial rank and authority, and to recollect with pleasure the pomp of those brief days of enjoyment, when military men of noble station were her admirers. Arnold had no counsellor on his pillow to urge him to the imitation of homely republican virtue, to stimulate him to follow the rugged path of a Revolutionary patriot. He fell, and though his wife did not tempt or counsel him to ruin, there is no reason to think she ever uttered a word or made a sign to deter him.”

Her instrumentality in the intercourse carried on while the iniquitous plan was maturing, according to all probability, was an unconscious one. Major Andrè, who had been intimate in her father’s family while General Howe was in possession of Philadelphia, wrote to her from New York, in August, 1779, to solicit her remembrance, and offer his services in procuring supplies, should she require any, in the millinery department, in which, he says playfully, the Mischianza had given him skill and experience. The period at which this missive was sent – more than a year after Andrè had parted with the “fair circle” for which he professes such lively regard, and the singularity of the letter itself, justified the suspicion which became general after its seizure by the Council of Pennsylvania – that its offer of service in the detail of capwire, needles, and gauze, covered a meaning deep and dangerous. This view was taken by many writers of the day; but, admitting that the letter was intended to convey a mysterious meaning, still, it is not conclusive evidence of Mrs. Arnold’s participation in the design or knowledge of the treason, the consummation of which was yet distant more than a year. The suggestion of Mr. Reed seems more probable – that the guilty correspondence between the two officers under feigned names having been commenced in March or April, the letter to Mrs. Arnold may have been intended by Andrè to inform her husband of the name and rank of his New York correspondent, and thus encourage a fuller measure of confidence and regard. The judgment of Mr. Reed, Mr. Sparks, and others who have closely investigated the subject, is in favor of Mrs. Arnold’s innocence in the matter.

It was after the plot was far advanced towards its denouement, and only two days before General Washington commenced his tour to Hartford, in the course of which he made his visit at West Point, that Mrs. Arnold came thither, with her infant, to join her husband, travelling by short stages, in her own carriage. She passed the last night at Smith’s house, where she was met by the General, and proceeded up the river in his barge to head-quarters. When Washington and his officers arrived at West Point, having sent from Fishkill to announce their coming, La Fayette reminded the Chief, who was turning his horse into a road leading to the river, that Mrs. Arnold would be waiting breakfast; to which Washington sportively answered: “Ah, you young men are all in love with Mrs. Arnold, and wish to get where she is as soon as possible. Go, breakfast with her – and do not wait for me.”

Mrs. Arnold was at breakfast with her husband and the aids-de-camp – Washington and the other officers having not yet come – when the letter arrived which bore to the traitor the first intelligence of Andrè’s capture. He left the room immediately, went to his wife’s chamber, sent for her, and briefly informed her of the necessity of his instant flight to the enemy. This was, probably, the first intelligence she received of what had been so long going on; the news overwhelmed her, and when Arnold quitted the apartment, he left her lying in a swoon on the floor.

Her almost frantic condition – plunged into the depths of distress – is described with sympathy by Colonel Hamilton, in a letter written the next day: “The General,” he says, “went to see her; she upbralded him with being in a plot to murder her child, raved, shed tears, and lamented the fate of the infant. . . . All the sweetness of beauty – all the loveliness of innocence – all the tenderness of a wife, and all the fondness of a mother, showed themselves in her appearance and conduct.” He, too, expresses his conviction that she had no knowledge of Arnold’s plan, till his announcement to her that he must banish himself from his country for ever. The opinion of other persons qualified to judge without prejudice, acquitted her of the charge of having participated in the treason. John Jay, writing from Madrid to Catharine Livingston, says: “All the world here are cursing Arnold, and pitying his wife.” And Robert Morris writes: “Poor Mrs. Arnold ! was there ever such an infernal villain !”

Mrs. Arnold went from West Point to her father’s house; but was not long permitted to remain in Philadelphia. The traitor’s papers having been seized, by direction of the Executive Authorities, the correspondence with Andrè was brought to life; suspicion rested on her; and by an order of the Council dated October 27th, she was required to leave the State, to return no more during the continuance of the war. She accordingly departed to join her husband in New York. The respect and forbearance shown towards her on her journey through the country, notwithstanding her banishment, testified the popular belief in her innocence. M. de Marbois relates that when she stopped at a village where the people were about to burn Arnold in effigy, they put it off till the next night. And when she entered the carriage on her way to join her husband, all exhibition of popular indignation was suspended, as if respectful pity for the grief and shame she suffered for the time overcame every other feeling.

Mrs. Arnold resided with her husband for a time in the city of St. Johns, New Brunswick, and was long remembered by persons who knew her there, and who spoke much of her beauty and fascination. She afterwards lived in England. Mr. Sabine says that she and Arnold were seen by an American loyalist in Westminster Abbey, standing before the cenotaph erected by command of the king, in memory of the unfortunate Andrè. With what feelings the traitor viewed the monument of the man his crime had sacrificed, is not known; but he who saw him standing there turned away with horror.

Mrs. Arnold survived her husband three years, and died in London in 1804, at the age of forty-three. Little is known of her after the blasting of the bright promise of her youth by her husband’s crime, and a dreary obscurity hangs over the close of her career; but her relatives in Philadelphia cherish her memory with respect and affection.

Hannah, the sister of Arnold, whose affection followed him through his guilty career, possessed great excellence of character; but no particulars have been obtained, by which full justice could be done to her. Mr. Sabine says: “That she was a true woman in the highest possible sense, I do not entertain a doubt;” and the same opinion of her is expressed by Mr. Sparks.