Contents

Contents

The Molasses Act of 1733 was a tax on imported sugar and molasses imposed by Great Britain in the Thirteen Colonies.

The law targeted sugar and molasses from foreign sources, such as the French West Indies.

Why was the Molasses Act passed?

The Molasses Act was designed not to raise tax revenue, but to increase trade with British merchants, in locations such as the British West Indies.

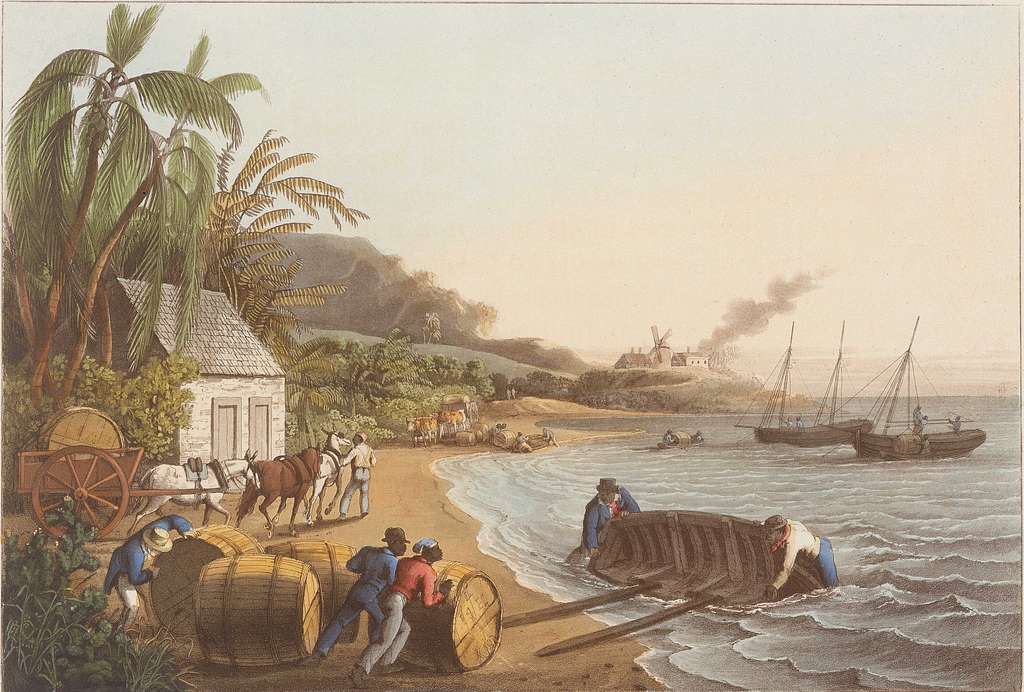

In the early 18th century, molasses was in high demand in the New World, especially in New England, where it was used to produce rum.

Sugar, including in its liquid form, molasses, was imported from the Caribbean, and distilled into rum in the colonies. Then, it was exported back to the West Indies, Europe, and Africa. The New England economy was heavily reliant on the rum trade.

Most of the rum imported into the colonies came from non-British overseas territories. Rum was often cheaper when purchased from French or Dutch colonies in the West Indies like Martinique and Sint Maarten, compared to British West Indies territories like Barbados and Jamaica.

Powerful British plantation owners in the West Indies complained that they were being undercut by foreign suppliers. As a result, the British government stepped in to try and prevent American colonial trade with foreign sources of molasses.

What was the Molasses Act?

The Molasses Act introduced a tax of six pence per gallon on foreign sugar and molasses imported into the American colonies. Imports from British colonial territories were exempt from the tax.

The Molasses Act also targeted rum imports from foreign sources, at a rate of nine pence per gallon, to try and stimulate trade with British rum producers in the Caribbean.

While New England produced a significant quantity of rum, it was not sufficient to meet domestic demand given the quantity exported, and Great Britain wanted the colonists to rely on other British merchants to make up the shortfall.

The taxes were to be collected by British customs officers in the Thirteen Colonies.

From and after the Twenty-fifth Day of December, One thousand Seven hundred and thirty three, there shall be raised, levied, collected, and paid… upon all Molasses or Syrups of such Foreign Produce or Manufacture… the Sum of Six pence of like Money, for every Gallon thereof…

Effects

The Molasses Act threatened to significantly disrupt the colonial economy, especially in New England. However, the Act was ultimately ineffective as the colonists found workarounds to the new law.

Rather than paying the import duty required, or importing British molasses, most colonial merchants began illegally smuggling rum ingredients into the Thirteen Colonies from the same suppliers as before.

It was normally straightforward to bribe or intimidate a customs officer to avoid the tax, and in general, the regulations were not strictly enforced, partly due to the scale of noncompliance among colonial merchants.

Many historians consider the act economically counterproductive, as it disrupted colonial economies without significantly benefiting British plantations.

Colonial reaction

The Molasses Act did not lead to widespread outrage and mass protests in the Thirteen Colonies, but it did significantly upset certain demographic groups, especially in New England.

Those involved in the rum industry, as well as people working in key port cities like Boston, felt that the tax was extremely unfair, as it threatened to wipe out their livelihoods, seemingly just for the sake of enriching British plantation owners in the West Indies.

The Act was one of the first actions of the British government that significantly broke colonial trust, and threatened the colonists’ autonomy that they had largely enjoyed uninterrupted for much of the 17th century, under a British policy known as salutary neglect.

Eventually, after the end of the French and Indian War in 1763, the British began implementing new taxes with the intent to enforce them more strictly, leading to widespread resistance, and eventually all-out war.

For example, the Molasses Act was replaced by the Sugar Act of 1764. Although the taxes were reduced under the new law, it saw significant resistance from colonial merchants and politicians, leading to its repeal in 1766.