Contents

Contents

Chapters

- Chapter 1: The Opening of Hostilities, 1775

- Chapter 2: Naval Administration and Organization

- Chapter 3: Washington’s Fleet, 1775 and 1776

- Chapter 4: The New Providence Expedition, 1776

- Chapter 5: Other Events in the Sea in 1776

- Chapter 6: Lake Champlain, 1776

- Chapter 7: Naval Operations in 1777

- Chapter 8: Foreign Relations, 1777

- Chapter 9: Naval Operations in 1778

- Chapter 10: European Waters in 1778

- Chapter 11: Naval Operations in 1779

- Chapter 12: The Penobscot Expedition, 1779

- Chapter 13: A Cruise Around the British Isles, 1779

- Chapter 14: Naval Operations in 1780

- Chapter 15: European Waters in 1780

- Chapter 16: Naval Operations in 1781

- Chapter 17: The End of the War, 1782 and 1783

- Chapter 18: Naval Prisoners

- Chapter 19: Naval Conditions of the Revolution

- Appendix

The Naval Committee was busy during the winter of 1775 and 1776 fitting out the four vessels which had been purchased in November – the Alfred, Columbus, Andrew Doria, and Cabot. Commodore Hopkins arrived in Philadelphia early in the winter on board the sloop Katy, Captain Whipple, which brought seamen from Rhode Island to man the fleet (Hopkins,81; R.I. Hist. Mag., July, 1885, journal of Lieutenant Trevett.) The Katy was taken into the navy and called the Providence. Three other vessels were added to the fleet – a sloop named the Hornet and two schooners, the Wasp and Fly. The Hornet and Wasp were at Baltimore.

On January 5, 1776, the Naval Committee issued “Orders and Directions for the Commander in Chief of the Fleet of the United Colonies.” These general instructions related to discipline and to matters concerning the management of the fleet. The commodore was to correspond regularly with Congress “and with the commander in chief of the Continental forces in America.” He was to give his orders to subordinate officers in writing, and the captains of the fleet were to make him monthly returns of conditions on board each vessel, the state of the ship and of the crew and the quantity of stores and provisions. He was to give directions for the captains to follow in case of separation; to appoint officers for any vessels that might be captured; to give special attention to the care of the men under his command and to the arms and ammunition; and prisoners were to “be well and humanely treated.” (Am. Arch., IV, iv, 578; Hopkins, 84.)

The committee also gave the commodore special instructions and sailing orders of the same date. He was “to proceed with the said fleet to sea and, if the winds and weather will possibly admit of it, to proceed directly for Chesapeak Bay in Virginia, and when nearly arrived there you will send forward a small swift sailing vessel to gain intelligence of the enemies situation and strength. If by such intelligence you find that they are not greatly superior to your own, you are immediately to enter the said bay, search out and attack, take or destroy all the naval force of our enemies that you may find there. If you should be so fortunate as to execute this business successfully in Virginia, you are then to proceed immediately to the southward and make yourself master of such forces as the enemy may have both in North and South Carolina, in such manner as you may think most prudent from the intelligence you shall receive, either by dividing your fleet or keeping it together. Having compleated your business in the Carolinas, you are without delay to proceed northward directly to Rhode Island and attack, take and destroy all the enemies naval force that you may find there.” He was also ordered to seize transports and supply vessels, advised as to the disposal of prisoners, and directed to fit out his prizes for service when suitable and appoint officers for them, calling on the assemblies and committees of safety of the various colonies for aid, if necessary, in all matters. Notwithstanding these particular orders which it is hoped you will be able to execute, if bad winds or stormy weather or any other unforseen accident or disaster disable you so to do, you are then to follow such courses as your best judgment shall suggest to you as most useful to the American cause and to distress the enemy by all means in your power.” (Hopkins, 94-97.)

In the fall of 1775, Governor Dunmore of Virginia organized a flotilla of small vessels in the Chesapeake with which he ravaged the shores of the bay and of the rivers flowing into it (See infra, and ch. 5.) It was for the purpose of attempting the destruction of this fleet that Hopkins was ordered to begin his cruise by entering Chesapeake Bay.

The Alfred was selected as the flagship of the fleet, and when she was ready to be put into commission the commodore went on board and the Continental colors were hoisted by Lieutenant John Paul Jones, for the first time on any regular naval vessel of the United States, and were properly saluted. This was a yellow flag bearing “a lively representation of a rattlesnake,” with the motto “Don’t tread on me.” The exact date of this ceremony is uncertain (Hopkins, 98; Am. Arch., IV, iv, 360.)

The ice in the river delayed the sailing of the expedition, which it was hoped would get away by the middle of January. Meanwhile on the 4th the following notice was published: “The Naval Committee give possitive orders that every Officer in the Sea and Marine Service, and all the Common Men belonging to each, who have enlisted into the Service of the United Colonies on board the ships now fiting out, that they immediately repair on board their respective ships as they would avoid being deemed deserters, and all those who have undertaken to be security for any of them are hereby called upon to procure and deliver up the men they have engaged for, or they will be immediately called upon in a proper and effectual way.”(Brit. Adm. Rec., A. D. 484, March 8, 1776, No. 5, from a copy sent to the British admiral.) On the same day the four largest vessels cast off from the wharf at Philadelphia, but were unable to make way through the ice until January 17, and then only as far as Reedy Island on the Delaware side of the river. Here they remained until February 11, when, having been joined by the Providence and Fly, they proceeded down to Cape Henlopen. The Hornet and Wasp, having come around from Baltimore, arrived in Delaware Bay on the 13th; these two are believed to have been the first vessels of the Continental navy to get to sea. The fleet sailed from the Delaware February 17, 1776 (Hopkins, 91, 100; Am. Arch., IV, v, 823; Brit. Adm. Rec., A. D. 484, March 8, 1776, No. 10; Ibid., July 8, 1776, inclosing ” A Journal of a Cruse In the Brig Andrew Doria,” taken in a recaptured prize.)

The force was made up as follows: the ships Alfred, 24, flagship, Commodore Hopkins and Captain Saltonstall, and Columbus, 20, Captain Whipple; the brigs Andrew Doria, 14, Captain Biddle, and Cabot, 14, Captain John B. Hopkins, son of the commodore; the sloops Providence, 12, Captain Hazard, and Hornet, 10, Captain Stone; and the schooners Fly, 8, Captain Hacker, and Wasp, 8, Captain Alexander. Each of the first two was manned by a crew of two hundred and twenty, including sixty marines; the Alfred carried twenty and the Columbus eighteen nine-pounders on the lower deck, with ten sixes on the upper deck. The Andrew Doria and the Cabot were armed with six-pounders, the former having sixteen, the latter fourteen, and each carried twelve swivels; the Doria had a crew of a hundred and thirty and the Cabot a hundred and twenty, with thirty marines in each case. The Providence, though sometimes called a brig, was rigged as a sloop, and mounted twelve six-pounders and ten swivels; her crew consisted of ninety men including twenty-eight marines (Brit. Adm. Rec., A. D. 484, March 8, 1777, No. 4, being information collected by agents of the British admiral, a source not always perfectly reliable.)

It is evident that several days before sailing Hopkins had determined to disregard his instructions and, taking advantage of the discretion allowed him in case of unforeseen difficulties, to abandon the projected cruise along the southern coast. In his first orders to his captains, dated February 14, three days before his departure, he says: “In Case you should be separated in a Gale of Wind or otherwise, you then are to use all possible Means to join the Fleet as soon as possible. But if you cannot in four days after you leave the Fleet, You are to make the best of your way to the Southern part of Abaco, one of the Bahama Islands, and there wait for the Fleet fourteen days. But if the Fleet does not join you in that time, You are to Cruise in such place as you think will most Annoy the Enemy and you are to send into port for Tryal all British Vessels or Property, or other Vessels with any Supplies for the Ministerial Forces, who you may make Yourself Master of, to such place as you may think best within the United Colonies.” (MS. Orders to Captain Hacker.) At the same time the Commodore furnished the Captains with a very complete set of signals. In appointing a rendezvous at Abaco, Hopkins had in mind a descent upon the island of New Providence in the Bahama group, for the purpose of seizing a quantity of powder known to be stored there. Scarcity of powder was a cause of the greatest anxiety to Washington, especially during the first year of the war. Congress in secret session had considered the feasibility of obtaining powder from New Providence (Am. Arch., IV, iv, 1179, 1180; Hopkins, 101; Jour. Cont. Congr., November 29, 1775.)

In his report of the expedition, addressed to the President of Congress and dated April 9, 1776, Hopkins says: “When I put to Sea the 17th Febry. from Cape Henlopen, we had many Sick and four of the Vessels had a large number on board with the Small Pox. The Hornet & Wasp join’d me two days before. The Wind came at N. E. which made it unsafe to lye there. The Wind after we got out came on to blow hard. I did not think we were in a Condition to keep on a Cold Coast and appointed our Rendezvous at Abaco, one of the Bahama Islands. The second night we lost the Hornet and Fly.” (Pap. Cont. Congr., 78, 11, 33; Ain. Arch., IV, v, 823.) From this it would seem to have been the commodore’s purpose to give the impression that the state of the weather after be got to sea had caused him to change his plans; whereas be had fully made up his mind in advance.

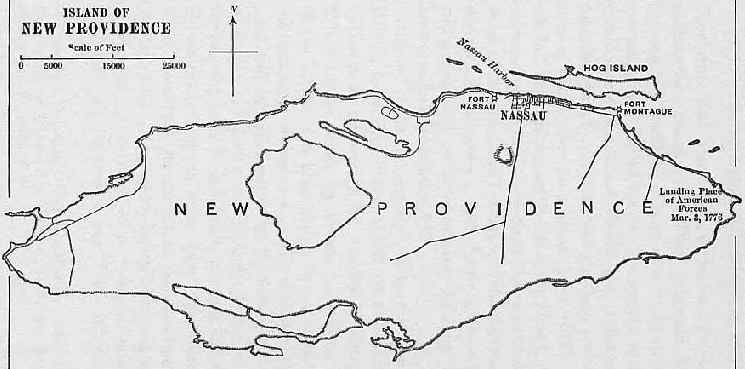

The fleet arrived at Abaco March 1. Hopkins says: “I then formed an Expedition against New Providence which I put in Execution the 3rd March by Landing 200 Marines under the Command of Captn. Nicholas and 50 Sailors under the Command of Lieutt. Weaver of the Cabot, who was well acquainted there.” Two sloops from New Providence had been seized, to be used for transporting the landing party. They embarked Saturday evening March 2. The next morning the fleet got under way and at 10 o’clock came to at some distance from the island. It had been intended to take the place by surprise, but the fleet had been seen and the forts fired alarm guns. “We then ran in,” says Lieutenant Jones of the Alfred, “and anchored at a small key three leagues to windward of the town, and from thence the Commodore despatched the marines, with the sloop Providence and schooner Wasp to cover their landing. They landed without opposition.” (Pap. Cont. Congr., 78, 11, 33; Journal of the Andrew Doria; Sherburne’s life of John Paul Jones, 12. For an account of the expedition, see Hopkins, ch. iv.)

Samuel Nicholas, captain of marines on the Alfred, in a letter dated April 10, says that on March 3, at two o’clock he “landed all our men, 270 in number under my command, at the east end of the Island at a place called New-Guinea. The inhabitants were very much alarmed at our appearance and supposed us to be Spaniards, but were soon undeceived after our landing. Just as I had formed the men I received a message from the Governor desiring to know what our intentions were. I sent him for answer, to take possession of all the warlike stores on the Island belonging to the crown, but had no design of touching the property or hurting the persons of any of the inhabitants, unless in our defence. As soon as the messenger was gone I marched forward to take possession of Fort Montague, a fortification built of stone, about half way between our landing place and the town. As we approached the fort (within about a mile, having a deep cove to go round, with a prodigious thicket on one side and the water on the other, entirely open to their view) they fired three twelve pound shot, which made us halt and consult what was best to be done. We then thought it more prudent to send a flag to let them know what our designs were in coming there; we soon received an answer letting us know that it was by the Governor’s orders that they had fired. They spiked up the cannon and abandoned the fort and retired to the fort within the town. I then marched and took possession of it.” (Mass. Spy, May 10, 1776; Am. Arch., IV, v, 846.) In the fort were found seventeen cannon, thirty-two-pounders, eighteens and twelves, from which the spikes were easily removed. Nicholas and his men spent the night in the fort. In the evening Hopkins, hearing that there was a force of over two hundred men in the main fort at Nassau, published a manifesto addressed to the inhabitants of the island declaring his intention “to take possession of the powder and warlike stores belonging to the Crown and if I am not opposed in putting my design in execution, the persons and property of the inhabitants shall be safe, neither shall they be suffered to be hurt in case they make no resistance.” (Am. Arch., IV, v, 46.) This had a good effect and no opposition was met with.

“The next morning by daylight,” says Nicholas, we marched forward to the town, to take possession of the Governor’s house, which stands on an eminence with two four pounders, which commands the garrison and town. On our march I met an express from the Governor to the same purport as the first; I sent him the same answer as before. The messenger then told me I might march into the town and if I thought proper into the fort, without interruption; on which I marched into the town. I then drafted a guard and went up to the Governor’s and demanded the keys of the fort, which were given to me immediately; and then took possession of fort Nassau. In it there were about forty cannon mounted and well loaded for our reception, with round, langridge and cannister shot; all this was accomplished without firing a single shot from our side.” (Mass. Spy, May 10, 1776.) The fleet, which had been lying behind Hog Island, soon afterwards came into the harbor; the commodore and captains then landed and came up to the fort. In Fort Nassau were found great quantities of military stores, including seventy-one cannon – ranging in size from nine-pounders to thirty-twos, fifteen brass mortars, and twenty-four casks of powder. The governor had contrived to send off a hundred and fifty casks of powder the night before, thereby defeating in great measure the main object sought in taking the island. The value of the property brought away, however, largely made up for this disappointment. After this the governor was kept under guard in his own house until the fleet was ready to sail. About two weeks were occupied in loading the captured stores on board the fleet, and it was necessary to impress a large sloop in order to carry everything. This vessel, called the Endeavor, was put under the command of Lieutenant Hinman of the Cabot. During this time the Fly rejoined the fleet and “gave an Account that he got foul of the Hornet and carried away the Boom and head of her Mast and I hear since she has got into some port of South Carolina.” It afterwards turned out that the Hornet was driven off the coast of South Carolina by bad weather and finally succeeded in getting back into Delaware Bay about April 1. Hopkins took on board the fleet as prisoners the governor and lieutenant-governor of New Providence and another high official (Mass. Spy, May 10, 1776; Am Arch., IV, v, 407, 823, 824; R.I. Hist. May., July, 1885; Life of Joshua Barney, 31-33.)

The fleet set sail on the return voyage March 17. The next day Hopkins issued orders to his captains: “You are to keep company with the ship I am in if possible, but should you separate by accident you are then to make the best of your way to Block Island Channel and there to cruise in 30 fathom water south from Block Island six days, in order to join the fleet. If they do not join you in that time, you may cruise in such places as you think will most annoy the Enemy or go in Port, as you think fit.” (Am. Arch., IV, v, 47.) The Wasp parted from the fleet soon after sailing. For over two weeks the voyage to Rhode Island was uneventful. April 4 the British six-gun schooner Hawk was captured by the Columbus. The Hawk belonged to the British fleet at Newport. Captain Nicholas says: “We made Block Island in the afternoon [of the 4th] ; the Commodore then gave orders to the brigs to stand in for Rhode-Island, to see if any more of the fleet were out and join us next morning, which was accordingly done, but without seeing any vessels.” At daylight the brig Bolton was taken by the Alfred after firing a few shots; she was a bomb-vessel of eight guns and two howitzers. The fleet cruised all day in sight of Block Island, and in the evening took a brigantine and sloop from New York. 1, We had at sunset 12 sail, a very pleasant evening.” (Mass. Spy, May 10, 1776.)

Of the events of the night Hopkins gives a brief account in his report. Very early in the morning of April 6 the fleet “fell in with the Glascow and her Tender and Engaged her near three hours. We lost 6 Men Killed and as many Wounded; the Cabot had 4 Men killed and 7 Wounded, the Captain is among the latter; the Columbus had one Man who lost his Arm. We received a considerable damage in our Ship, but the greatest was in having our Wheel Ropes & Blocks shott away, which gave the Glascow time to make Sail, which I did not think proper to follow as it would have brought an Action with the whole of their Fleet and as I had upwards of 30 of our best Seamen on board the Prizes, and some that were on board had got too much Liquor out of the Prizes to be fit for Duty. Thought it most prudent to give over Chace and Secure our Prizes & got nothing but the Glascow’s Tender and arrived here [New London] the 7th with all the Fleet. . . . The Officers all behaved well on board the Alfred, but too much praise cannot be given to the Officers of the Cabot, who gave and sustained the whole Fire for some considerable time within Pistol Shott.” (Pap. Cont. Congr., 78, 11, 33.)

Nicholas gives a more minute recital of the affair: ,At 12 o’clock went to bed and at half past one was awaked by the noise of all hands to quarters; we were soon ready for action. The best part of my company with my first Lieut. was placed in the barge on the main deck, the remaining part with my second Lieutenant and myself on the quarter deck. We had discovered a large ship standing directly for us. The Cabot was foremost of the fleet, our ship close after, not more than 100 yards behind, but to windward with all, when the brigantine came close up. The ship hailed and was soon answered by the Cabot, who soon found her to be the Glasgow; the brigantine immediately fired her broadside and instantly received a return of two fold, which, owing to the weight of metal, damaged her so much in her hull and rigging as obliged her to retire for a while to refit. We then came up, not having it in our power to fire a shot before without hurting the brigantine, and engaged her side by side for three glasses as hot as possibly could be on both sides. The first broadside she fired, my second Lieutenant fell dead close by my side; he was shot by a musket ball through the head.” (Mass. Spy, May 10, 1776.)

John Paul Jones’s narrative of the action in the Alfred’s log-book gives a few additional details: “At 2 A.M. cleared ship for action. At half past two the Cabot, being between us and the enemy, began to engage and soon after we did the same. At the third glass the enemy bore away and by crowding sail at length got a considerable way ahead, made signals for the rest of the English fleet at Rhode Island to come to her assistance, and steered directly for the harbor. The Commodore then thought it imprudent to risk our prizes, &c. by pursuing farther; therefore, to prevent our being decoyed into their hands, at half past six made the signal to leave off chase and haul by the wind to join our prizes. The Cabot was disabled at the second broadside, the captain being dangerously wounded, the master and several men killed. The enemy’s whole fire was then directed at us and an unlucky shot having carried away our wheel-block and ropes, the ship broached to and gave the enemy an opportunity of raking us with several broadsides before we were again in condition to steer the ship and return the fire. In the action we received several shot under water, which made the ship very leaky; we had besides the mainmast shot through and the upper works and rigging very considerably damaged.” (Sherburne, 14.)

Captain Whipple of the Columbus reported to the commodore that when the Glasgow was sighted he was to leeward and “hauled up for her,” but the position of the other ships “Instantly kill’d all the wind, which put it out of my Power to get up with her. I strove all in my Power, but in vain; before that I had got close enough for a Close Engagement, the Glasgow had made all Sail for the Harbour of Newport. I continued Chace under all Sail that I had, except Steering Sails and the Wind being before the Beam, she firing her two Stern Chaces into me as fast as possible and my keeping up a Fire with my Bow Guns and now and then a Broadside, put it out of my Power to get near enough to have a close Engagement. I continued this Chace while you thought proper to hoist a Signal to return into the Fleet; I accordingly Obeyed the Signal.” (Hopkins, 130, 131; Am. Arch., IV, v, 1156.)

Apparently the Andrew Doria was less closely engaged than the others. One of her officers, Lieutenant Josiah, says that the Cabot having fired the first broadside at the Glasgow, “she return’d two fold, which oblig’d ye Cabot to sheer off and had like to have been foul of us, which oblig’d us to tack to gett clear; the Commodore came up next and Discharg’d several Broadside and received as many, which did Considerable Damage in his hull & Riggen, which oblig’d him to sheer off. The Glascow then made all the sail she possible could for Newport & made a running fight for 7 Glases. We receiv’d several shott in ye hull & riggen, one upon the Quarter through the Netting and stove ye arm Chest upon the Quarter Deck and wounded our Drummer in ye Legg.” (Journal of the Andrew Doria.)

The Glasgow was a ship of twenty guns and a hundred and fifty men, commanded by Captain Tyringham Howe, whose report of the engagement says: “On Saturday the 6th of April, 1776, At two A.M. Block Island then bearing N. W. about eight Leagues, we discovered a Fleet on the weather beam, consisting of seven or eight Sail; tacked and stood towards them and soon perceived them to be two or three large Ships and other Square Rigged Vessels. Turned all hands to Quarters, hauled up the Mainsail and kept standing on to the N. W. with a light breeze and smooth Water, the Fleet then coming down before it. At half past two a large Brig, much like the Bolton but larger, came within hail and seemed to hesitate about giving any answer, but still kept standing towards us and on being asked what other Ships were in company with her, they answered ‘the Columbus and Alfred, a two and twenty Gun frigate.’ And almost immediately a hand Grenadoe was thrown out of her top. We exchanged our- Broadsides. She then shot a head and lay on our bow, to make room for a large Ship with a top-light to come on our Broadside and another Ship ran under our Stern, Raked as she passed and then luft up on our Lee beam, whilst a Brig took her Station on our Larboard Quarter and a Sloop kept altering her Station occasionally. At this time the Clerk having the care of the dispatches for the So. Ward to destroy, if the ship should be boarded or in danger of being taken, hove the bag overboard with a shot in it. At four the Station of every Vessel was altered, as the two ships had dropt on each quarter and a Brig kept a stern giving a continual fire. Bore away and made Sail for Rhode Island, with the whole fleet within Musket shot on our Quarters and Stern. Got two Stern chase guns out of the Cabin and kept giving and receiving a very warm fire. At daylight perceived the Rebel fleet to consist of two Ships, two Brigs and a Sloop, and a large Ship and Snow that kept to Windward as soon as the Action began. At half past six the Fleet hauled their Wind and at Seven tacked and stood to the S. S. W. Employed reeving, knotting and splicing and the Carpenters making fishes for the Masts. At half past seven made a Signal and fired several guns occasionally to alarm the fleet at Rhode Island Harbour. The Rose, Swan and Nautilus then being working out. We had one Man Killed and three Wounded by the musketry from the Enemy.” (Brit. Adm. Rec., A. D. 484, April 19,1776; London Chronicle, June 11, 1776; briefer accounts in Brit. Adm. Rec., Captains’ Letters, No. 1902, 22 (April 27, 1776), and Captains’ Logs, No. 398 (April 6, 1776)

An American prisoner on board the Glasgow says that the sloop Providence, joining in the attack, directed her fire at the Glasgows’ “stern without any great effect. The most of her shot went about six feet above the deck; whereas, if they had been properly levelled, they must soon have cleared it of men. The Glasgow got at a distance, when she fired smartly, and the engagement lasted about six glasses, when they both seemed willing to quit. The Glasgow was considerably damaged in her hull, had ten shot through her mainmast, fifty-two through her mizen staysail, one hundred and ten through mainsail, and eighty-eight through her foresail; had her spars carried away and her rigging cut to pieces.” (Constitutional Gazette, New York, May 29, 1776, quoted in Sands, 45, 46.)

The Glasgow was seriously crippled and her escape from a superior force shows a lack of cooperation on the part of the Continental fleet, and perhaps excessive prudence in not carrying the pursuit farther towards Newport. It was an instance of the want of naval training and esprit de corps to be expected in a new, raw service. Moreover, the American vessels, except the Alfred, were inferior sailing craft to begin with, and besides this were too deeply laden with the military stores brought from New Providence to be easily and quickly handled.

Hopkins took his fleet and prizes into New London April 8. Here over two hundred sick men were landed; also the military stores. The next day the Andrew Doria was sent out on a short cruise and recaptured a prize from the British. Some of the heavy guns from New Providence were sent to Dartmouth, on Buzzard’s Bay; and upon the departure of the British from Narragansett Bay soon afterwards, the Cabot, Captain Hinman, was sent to Newport with several of the guns. The prisoners brought from New Providence were paroled. The commodore’s report of April 9 was read in Congress and published in the newspapers. It caused great satisfaction, and Hopkins received a letter of congratulation from John Hancock, the President of Congress. His popularity at this time, both in the fleet and among the people, seems to have been genuine. The Marine Committee suggested the purchase of the prize schooner Hawk for the service, to be renamed the Hopkins. John Paul Jones, who as a lieutenant on the Alfred had had an opportunity to estimate the commodore’s qualifications, wrote of him, April 14: “I have the pleasure of assuring you that the commander-in-chief is respected through the fleet and I verily believe that the officers and men in general would go any length to execute his orders.” (Sherburne, 13.) There was a reaction, however, later on. Upon reflection people came to the opinion that the escape of the Glasgow was unnecessary and discreditable. Captain Whipple was accused of cowardice and demanded a court-martial, by which he was honorably acquitted. Captain Hazard of the Providence was less fortunate; he also was court-martialed and was relieved of his command. (Am. Arch., IV, v, 824, 867, 956, 966, 1005, 1111, 1156, 1168, vi, 409, 552, 553; Hopkins, 125-135 ; Journal of the Andrew Doria.)

The British fleet, consisting of the frigate Rose, the Glasgow, the Nautilus, Swan, and several tenders, had found Newport Harbor an uncomfortable anchorage. April 5 they went to sea, but all except the Glasgow and her tender returned in the evening and anchored off Coddington Point, north of Newport. At daylight the next morning, while the Glasgow was engaged with the American fleet, the Continental troops mounted two eighteen-pounders on the point, opened fire, and drove them from their anchorage. When the Glasgow came in after her battle, she and some of the smaller vessels anchored off Brenton’s Point; the others went to sea. On the morning of the 7th the Glasgow and the vessels with her were fired upon by guns which had been mounted on Brenton’s Point during the night, and driven up the bay. Later they too went to sea and the whole fleet sailed for Halifax. April 11 another British man-of-war, the Phoenix, brought two prizes into Newport, but she was driven out again and the prizes recaptured (Boston Gazette, April 15, 22, 1776; Constitutional Gazette (New York), April 17, May 29, 1776, quoted in Sands, 46-48.) After the Glasgow had arrived at Halifax, Admiral Shuldham, in command of the station, wrote to the Admiralty that he found her “in so shattered a Condition and would require so much time and more Stores than there is in this Yard to put her into proper repair, I intend sending her to Plymouth as soon as she can be got ready.” (Brit. Adm. Rec., A. D. 484, April 19, 1776.)

Commodore Hopkins received one hundred and seventy men from the army to take the place of those he had lost through sickness. He then sailed, April 19, for Newport, but “the Alfred got ashore near Fisher’s Island and was obliged to be lightened to get her off, which we did without much damage.” They went back to New London and sailed again April 24; they went up to Providence the next day. There Hopkins landed over a hundred more sick men. Just at this time he received an order from Washington to send back to the army the men who had been loaned to him, as they were needed in New York. It was practically impossible to get recruits in Providence, because the attractions of privateering were so superior to those of the regular naval service. Delay in getting their pay for the first cruise also caused discontent and tended to make the service unpopular. The commodore had received information from the Marine Committee of two small British fleets in southern waters. A force organized by Governor Dunmore in Virginia consisted of the frigate Liverpool, 28, two sloops of war, and many small. vessels. “It is said & believed that both the Liverpool & Otter are exceedingly weak from the Want of Hands, their Men being chiefly employed on Board a Number of small Tenders fitted out by Lord Dunmore to distress the Trade on the Coast of Virginia & Bay of Chesepeak. His Lordship has now between 100 & 150 Sail of Vessels great & small, the most of which are Prizes & many of them valuable. Those, so far from being any Addition in point of Strength will rather weaken the Men of War, whose Hands are employed in the small Vessels.” The British had another naval force at Wilmington, North Carolina. “Whether you have formed any Expedition or not, the Execution of which will interfere with an Attempt upon either or both of the above Fleets we cannot determine; but if that should not be the Case, there is no Service from the present Appearance of things in which You could better promote the Interest of your Country than by the Destruction of the Enemie’s Fleet in North Carolina or Virginia; for as the Seat of War will most probably be transferred in the ensuing Campaign to the Southern Colonies, such a Maneuvre attended with Success will disconcert or at least retard their Military Operations for a Length of Time, give Spirits to our Friends & afford them an Opportunity of improving their Preparations for resistance.” (MS. Letter of Marine Committee, April, 1776.) Apparently because the Marine Committee became convinced that this plan was impracticable in view of the weak condition of the fleet, it was given up and, May 10, Hopkins was ordered. to send a squadron against the Newfoundland fishery. He himself had already been preparing for a four months’ cruise, but all such schemes now had to be abandoned for lack of seamen to man his fleet. Three vessels, however, were fitted out and sent away. The command of the Providence was given to Jones, May 10, and he was ordered to New York with the men who were to be returned to the army. The Andrew Doria and Cabot were sent off on a cruise May 19. The Fly was kept for a while on the lookout for British men-of-war off the entrance of Narragansett Bay. The Alfred and Columbus remained at Providence waiting for fresh crews. (Am; Arch., IV, v, 1001, 1005, 1079, 1140,1168, vi, 409, 410, 418, 430, 431, 551; Hopkins, 135-140; Journal of the Andrew Doria.)

Dissatisfaction with the conduct of Commodore Hopkins and some of his officers gradually increased in and out of Congress. Complaints of ill treatment on board the fleet, as well as instances of insubordination and desertion, came to the ears of the Marine Committee. All this of course still further increased the difficulty of manning the ships, with consequent delay apparently endless and the increasing probability of nothing important being accomplished. A committee of seven was appointed by Congress to investigate, and June 14 the commodore and Captains Saltonstall and Whipple were ordered to Philadelphia to appear before the Marine Committee and be interrogated in regard to their conduct. Saltonstall and Whipple were examined in July and were exonerated by Congress. The inquiry into Hopkins’s case came in August and he was questioned on three points: his alleged disobedience of orders in not visiting the southern coast during the cruise of his fleet; his poor management in permitting the escape of the Glasgow; and his inactivity since arriving in port. His defense was that, as he did not sail until six weeks after his orders were issued, conditions had changed, especially in regard to the force of the British, which had increased in Virginia and the Carolinas; but there is no mention of this in his report of April 9. He had written to his brother before the inquiry: “I intended to go from New Providence to Georgia, had I not received intelligence three or four days before I sailed that a frigate of twenty-eight guns had arrived there, which made the force in my opinion too strong for us. At Virginia they were likewise too strong. In Delaware and New York it would not do to attempt. Rhode Island I was sensible was stronger than we, but the force there was nearer equal than anywhere else, which was the reason of my attempts there.” (Hopkins, 154.) Hopkins was doubtless justified in using the discretion allowed him in his orders to depart from those orders in case of apparent necessity or expediency, and being on the spot he was presumably the best judge of the course to be pursued; but in order to establish his naval reputation it was incumbent upon him to convince others of the necessity or expediency. As to the second point, relating to the Glasgow, Hopkins seems to show a disposition to shift the blame upon his subordinates; no doubt some of his officers were not to be depended upon for prompt and efficient action. On the third point, the excessive amount of sickness in the fleet and the practical impossibility of obtaining recruits in sufficient numbers should have extenuated his shortcomings. There appears to have been a strong prejudice against Hopkins in Congress and it fared hard with him, although he was zealously and ably defended by John Adams. August 15, Congress resolved “that the said Commodore Hopkins, during his cruize to the southward, did not pay due regard to the tenor of his instructions, whereby he was expressly directed to annoy the enemy’s ships upon the coasts of the southern states; and that his reasons for not going from [New] Providence immediately to the Carolinas are by no means satisfactory.” The next day it was further resolved “that the said conduct of Commodore Hopkins deserves the censure of this house and the house does accordingly censure him.” Three days later he was ordered back to Rhode Island to resume command of his fleet (Am. Arch., IV, v, 1698, vi, 764, 885, 886,1678,1705, V, i, 994; Jour. Cont. Congr., August 15, 16, 1776; Hopkins, ch. v.)

Of the result of this inquiry John Adams wrote: “Although this resolution of censure was not in my opinion demanded by justice and consequently was inconsistent with good policy, as it tended to discourage an officer and diminish his authority by tarnishing his reputation, yet as it went not so far as to cashier him, which had been the object intended by the spirit that dictated the prosecution, I had the satisfaction to think that I had not labored wholly in vain in his defense.” (Hopkins, 160.) When John Paul Jones heard of the outcome he wrote a friendly and sympathetic letter to his commander, saying: “Your late trouble will tend to your future advantage by pointing out your friends and enemies. You will thereby be enabled to retain the one part while you guard against the other. You will be thrice welcome to your native land and to your nearest concerns.” (Ibid., 162.)

The fleet of Commodore Hopkins performed no further service collectively, but the fortunes of the various vessels composing it, during the remainder of the year 1776, may be conveniently followed here. The sloop Providence, having taken to New York the soldiers who had been borrowed from the army, returned to Providence, and in June was occupied for a while convoying vessels back and forth between Narragansett Bay and Long Island Sound. “In performing these last services Captain Jones found great difficulty from the enemy’s frigates then cruising round Block Island, with which he had several rencontres in one of which he saved a brigantine that was a stranger from Hispaniola, closely pursued by the Cerberus and laden with public military stores. That brigantine was afterwards purchased by the Continent and called the Hampden.” (Sands, 38 (Jones’s journal prepared at request of the king of France.) Jones was then ordered to Boston, where he collected a convoy which he conducted safely to Delaware Bay, arriving August 1. At this time the British fleet and army were on their way from Halifax to New York. Jones saw several of their ships, but was able to avoid them (Sands, 37, 38; Am. Arch., IV, vi, 418, 511, 820, 844, 972, 980.)

The Andrew Doria and Cabot sailed on a short cruise to the eastward May 19. Soon after getting to sea they were chased by the Cerberus and became separated. May 29, in latitude 41° 19′ north, longitude 57° 12′ west, the Andrew Doria captured two Scotch transports of the fleet bound to Boston. “At 4 A.M. saw two Ships to ye North’d, Made Sail and Hauld our Wind to ye North’d. At 6 Do. Brought the Northermost too, a Ship from Glascow . . . with 100 Highland Troops on Board & officers; made her hoist her Boat out & the Capt. came on board. Detained the Boat till we Brought the other too, from Glascow with ye same number of troops. [Lieutenant James Josiah, the writer of the journal] went on board and sent ye Capt. and four Men on board ye Brig [Andrew Doria], receiv’d orders for sending all the troops on board the other ship and went Prize master with Eleven Hands. Sent all the Arms on board ye Brig from both Ships, two Hundred & odd.” (Journal of the Andrew Doria.) These transports were the Crawford and Oxford. All the soldiers, two hundred and seventeen in number, with several women and children, were put on the Oxford. The Andrew Doria cruised with her prizes nearly two weeks and then, being to windward of Nantucket Shoals, they were chased by five British vessels. Captain Biddle signaled the transports to steer different courses and lost sight of them. The Crawford, in command of Lieutenant Josiah as prizemaster, was retaken by the Cerberus, but was captured again by the General Schuyler of Washington’s New York fleet (See ch. 3.) Josiah while a prisoner was treated with such severity as to occasion threats of retaliation, but he was eventually exchanged. On board the Oxford, containing the soldiers, the prize crew was overcome by the prisoners, who got possession of the ship and carried her into Hampton Roads. Their triumph was brief, however, for she was soon recaptured by Captain Barron of the Virginia navy. The next year the Oxford again fell into the hands of the British. The Andrew Doria put into Newport June 14 and soon went out again. She cruised most of the time during the rest of the year, taking several prizes. In October she changed her captain. The Columbus also went to sea in June and on the 18th had a brush with the Cerberus, losing one man. At this time there were three British frigates around Block Island. The Columbus took four or five prizes before the end of the year and the Cabot made a few captures. (Am. Arch., IV, vi, 430, 431, 539, 551, 902, 931, 972, 979, 998, 999, V, i, 659, 832, 1094, 1095, ii, 115, 132, 378, 1226, iii, 667, 848; Boston Gazette, June 24, July 29, September 16, 30, October 7, 28, 1776; N. E. (Independent) Chronicle, July 4, October 10, 1776; Military and Naval Mag. of U. S., June, 1834; So. Lit. Messenger, February, 1857; R. I. Hist. Mag., October, 1885; Brit. Adm. Rec., A. D. 484, July 8,1776, inclosing Journal of the Andrew Doria; Williams, 202.)

Captain Jones in the Providence sailed from Delaware Bay August 21. In the latitude of Bermuda he fell in with the British frigate Solebay, 28. “She sailed fast and pursued us by the wind, till after four hours chase, the sea running very cross, she got within musket shot of our lee quarter. As they had continued firing at us from the first without showing colours, I now ordered ours to be hoisted and began to fire at them. Upon this they also hoisted American colors and fired guns to leeward. But the bait would not take, for having everything prepared, I bore away before the wind and set all our light sail at once, so that before her sails could be trimmed and steering sails set, I was almost out of reach of grape and soon after out of reach of cannon shot . . . Had he foreseen this motion and been prepared to counteract it, he might have fired several broadsides of double-headed and grape shot, which would have done us very material damage. But he was a bad marksman, and though within pistol shot, did not touch the Providence with one of the many shots he fired.” (Sands, 49 (letter of September 4, 1776.) After cruising about two weeks longer, being short of water and wood, Jones decided to run into some port of Nova Scotia or Cape Breton. “I had besides,” he says, “a prospect of destroying the English shipping in these parts. The 16th and 17th [of September] I had a very heavy gale from the N. W. which obliged me to dismount all my guns and stick everything I could into the bold. The 19th I made the Isle of Sable and on the 20th, being between it and the main, I met with an English frigate [the Milford.], with a merchant ship under her convoy. I had hove to, to give my people an opportunity of taking fish, when the frigate came in sight directly to windward, and was so good natured as to save me the trouble of chasing him, by bearing down the instant he discovered us. When he came within cannon shot, I made sail to try his speed. Quartering and finding that I had the advantage, I shortened sail to give him a wild goose chase and tempt him to throw away powder and shot. Accordingly a curious mock engagement was maintained between us for eight hours,” until nightfall. “He excited my contempt so much by his continued firing at more than twice the proper distance, that when he rounded to, to give his broadside, I ordered my marine officer to return the salute with only a single musket. We saw him next morning, standing to the westward.” Jones then went into Canso and got a supply of wood and water; also several recruits. About a dozen fishing vessels were seized there and at the Island of Madame, three of which were released and as many more destroyed. “The evening of the 25th brought with it a violent gale of wind with rain, which obliged me to anchor in the entrance of Narrow Shock, where I rode it out with both anchors and whole cables ahead. Two of our prizes, the ship Alexander and [schooner] Sea Flower, had come out before the gale began. The ship anchored under a point and rode it out; but the schooner, after anchoring, drove and ran ashore. She was a valuable prize, but as I could not get her off, I next day ordered her to be set on fire. The schooner Ebenezer, taken at Canso, was driven on a reef of sunken rocks and there totally lost, the people having with difficulty saved themselves on a raft. Towards noon on the 26th the gale began to abate.” (Sands, 50, 51, 52 (September 30, 1776).) To remain longer in these waters, with so many prizes to protect, seemed an unwarrantable risk, and Jones therefore turned homeward. September 30 he was off Sable Island and just a week later in Newport Harbor. On this cruise he had ruined the fishery at Canso and Madame and had taken sixteen prizes; half of them were sent into port and the others destroyed or lost. (Am. Arch., V, i, 784, ii, 171-174, 624, 1105, 1226, 1303, 1304; Sands, 39, 48-54; Independent Chronicle, October 17, 1776; Boston Gazette, October 28, 1776.)

Jones proposed an expedition with three vessels to the west coast of Africa, where he was sure it would be possible to reap a rich harvest of prizes. Commodore Hopkins, however, determined to send a small squadron to Cape Breton in order to inflict further injury upon the fishery, and to attempt the capture of the coal fleet and the release of American prisoners working in the mines. The Alfred, with Jones in command of the expedition, and the Hampden, Captain Hacker, sailed towards the end of October. Jones wished to take the Providence also, but could not enlist a crew for her. At the outset, however, the Hampden ran on a ledge and was so injured that she was left behind, her crew being transferred to the Providence. The expedition, with the Alfred and Providence, made a fresh start November 1. On that day Jones issued instructions for Captain Hacker, saying: “The wind being now fair, we will proceed according to Orders for Spanish River near Cape North on the Island of Cape Briton”; and prescribing signals for foggy weather (MS. Letter.) On his way through Vineyard Sound, Jones boarded a Rhode Island privateer, acting under the orders of Commodore Hopkins, and impressed some deserters from the navy. Thence he proceeded directly for his cruising grounds and soon after his arrival, took three prizes off Louisburg. These were a brig and snow, which were sent back to American ports, and a large armed ship called the Mellish, with so rich a cargo of soldiers’ clothing that Jones kept her under convoy. He wrote to the Marine Committee, November 12: “This prize is, I believe, the most valuable that has been taken by the American arms. She made some defence, but it was trifling. The loss will distress the enemy more than can be easily imagined, as the clothing on board of her is the Last intended to be sent out for Canada this season and all that has preceded it is already taken. The situation of Burgoyne’s army must soon become insupportable. I shall not lose sight of a prize of such importance, but will sink her rather than suffer her to fall again into their hands.” (Sands, 56.) Jones afterwards recommended that the Mellish be armed and taken into the service.

A few days after this, during a stormy night, the Providence parted company and returned to Rhode Island; there had been discontent on this vessel among both officers and men, who represented that she leaked badly and was unsafe. Jones says that “previous to this step there had been an Unaccountable murmering in the Sloop for which I could see no Just foundation and in Vain had I represented to them how much humanity was concerned in our endeavours to relieve our Captive, ill treated Brethern from the Coal Mines. Since my arrival here I understand that as soon as Night came on they Put before the Wind. Being thus deserted the Epedemical discontent became General on Board the Alfred; the season was indeed Severe and everyone was for returning immediately to port, but I was determined at all hazards, while my provision lasted, to persevere in my first plan. When the Gale abated I found myself in sight of the N. E. Reef of the Isle of Sable & the wind continuing Northerly obliged me to beat up the South side of the Island. After exercising much Patience I weathered the N. W. Reef of the Island and on the 22d [of November], being off Canso, I sent my Boats in to Burn a Fine Transport with Irish Provision Bound for Canada., she having run aground within the Harbour; they were also ordered to Burn the Oil warehouse with the Contents and all the Materials for the Fishery, which having effected I carried off a small, fast sailing schooner which I purposed to Employ as a Tender instead of the Providence. On the 24th off Louisburg, it being thick weather, in the Afternoon I found myself surrounded by three Ships. Everyone Assured me that they were English Men of War and indeed I was of that opinion myself, for I had been informed by a Gentleman who came off from Canso that three Frigates on that Station had been Cruising for [me] ever since my expedition there in the Providence. Resolving to sell my liberty as dear as possible, I stood for and . . . Took the nearest; I took also the other two, tho’ they were at a Considerable distance assunder. These three Ships were . . . Transports Bound from the Coal Mines of Cape Briton for N. York Under Convoy of the Flora Frigate; they had Seen her a few hours before, and had the weather been clear she would then have been in sight. They left no Transports behind them at Spanish River, but they said the Roe Buck man of War was stationed there and that if there had been any Prisoners of ours there they had entered [the British service]. I made the best of my way to the Southward to prevent falling in with the Flora the next day, and on the 26th I fell in with and took a Ship of Ten Guns from Liverpool for Hallifax.” She was a letter of marque called the John. “I had now on Board an Hundred and Forty Prisoners, so that my Provision was consumed very Fast; I had the Mellish, the three Ships from the Coal Mines and the last taken Ship under Convoy; the best of my Sailors were sent on Board [these] Five Ships and the number left were barely sufficient to Guard the Prisoners. So that all circumstances considered, I concluded it most for the interest and Honor of the Service to Form the Prizes into a Squadron and proceed with them into Port. I was unfortunate in meeting with high Winds and Frequent Gales from the Westward. I however kept the Squadron together till the 7th of December on St Georges Bank, when a large Ship [the frigate Milford] Gave us chace. As she came so neare before Night that we could distinguish her as a Ship of War, I ordered the Mellish . . . and the rest of the Fastest Sailers to Crowd Sail and go a Head. I kept the Liverpool Ship with me, as She was of some Force and her Cargo by invoice not worth more than £1100 Sterling. In the Night I tacked and afterwards carried a Top light in order to lead the Enemy away from the Ships that had been ordered ahead. In the Morning they were out of Sight and I found the Enemy two points on my lee Quarter at the same distance as the night before. As the Alfred’s Provisions and Water were by this time almost entirely consumed, so that She sailed very ill by the Wind, and as the Ship I had by me, the John, made much less lee way, I ordered her to Fall a Stern to Windward of the Enemy and make the Signal Agreed on, if She was of Superiour or inferiour Force; that in the one Case we might each make the best of our way, or in the other come to Action. After a considerable time the Signal was made that the Enemy was of Superiour Force, but in the intrim the wind had encreased with Severe Squalls to a Hard Gale, so that in the Evening I drove the Alfred thro’ the Water Seven and Eight Knots under two Courses, a point from the Wind. Towards Night the Enemy Wore on the other Tack, but before that time the Sea had risen so very high that it was impossible to Hoist a Boat, so that had he been near the John it would have been impossible for him to have Taken her, unless they had wilfully given her up and continued voluntarily by the Enemy through the whole of the very dark and Stormy night that ensued.” Yet the John, however unnecessarily, surrendered to the Milford. Admiral Howe in reporting this affair says that the Alfred was chased “without effect, by means of the thick weather that critically happened and secured her Escape.” According to the log of the Milford a boat was lowered from the frigate and took possession of the John (Brit. Adm. Rec., A. D. 487, March 31, 1777, and Masters’ Logs, No. 1865 (log of Milford.) The report of Captain Jones goes on to say that in the evening of December 14, being then in Massachusetts Bay and fearing to be driven out, “I resolved to run into Plymouth, but in working up the Harbour the Ship missed Stays in a Violent Snow Squall on the South side, which obliged me to Anchor immediately in little more than three Fathom. She grounded at low water and Beat considerably, but we got her off in the morning and Arrived the 15th in the Nantasket Road with a tight ship and no perceptible damage whatever. I had then only two days provision left and the Number of my Prisoners brought in equalled the Number of my whole Crew when I left Rhode Island.” (Pap. Cont. Congr., 58, 107 (Jones to Marine Committee, January 12, 1777.) The John was apparently the only prize lost. The Mellish ran through Nantucket Shoals and got safely into Dartmouth. It was fortunate for Jones and for his valuable prize that fate did not lead them to Rhode Island, for a powerful British fleet had taken possession of Newport December 7 (Am. Arch., V, i, 1106, ii, 454, 1194, 1195, 1226, 1277, 1303, iii, 490, 491, 659, 668, 738, 789, 1162, 1281, 1282, 1283, 1284, 1356; Sands, 40-42, 54-57; Independent Chronicle, November 28, December 26, 1776; Boston Gazette, December 2, 23, 30, 1776; R.I. Hist. Mag., October, 1885. For experience of Lieutenant Trevett, as a spy in Newport soon after this, see Ibid., January, 1886.)

After Jones had sailed on this cruise in November, Hopkins received orders from the Marine Committee, dated October 10, 23, and 30, to proceed southward with the Alfred, Columbus, Cabot, Providence, and Hampden, or as many of them as were available; one or both of the new frigates under construction in Rhode Island might be joined to the squadron if they could be got ready for sea. He was to cruise in the neighborhood of Cape Fear, North Carolina, where he would find three British men-of-war with a large number of prizes and other vessels under their protection; and later perhaps still farther south. On the way to the Carolinas he was to look for two other British cruisers, the Galatea, 20, and Nautilus, 16, said to be off the Virginia capes. All these vessels, it was thought, might be captured or destroyed. “As this Service to the Southward is of much publick importance, we expect from Your Zeal and Attachment to the Interest of the United States that you proceed on and execute this Service with all possible Vigor and despatch.” (MS. Letter to Hopkins, October 23, 1776; Mar. Com. Letter Book, 38.)

Two of the vessels it was proposed to send were with Jones and others could not be manned without great delay; so the enterprise fell through. Some of the small vessels of Hopkins’s original fleet, however, were in more southern waters and performed what little service they could. In the spring of 1776 the Wasp and Hornet were in Delaware Bay and the former took part in an action with two British frigates (See ch, 5.) The Fly was sent to New York in June and after that, cruised along the New Jersey shore. The Wasp was ordered to Bermuda and the West Indies in August; she sent a valuable prize into Philadelphia and later joined the Fly. They were instructed by the Marine Committee, November 1 and 11, to keep a lookout for vessels going into and out of New York, now occupied by the British. Hopkins and Jones had also been ordered to intercept, when possible, storeships from Europe bound to New York. “We immagine there must be Transports, Store Ships and provision vessels daily arriving or expected to arrive at that place for supplying our enemies with provisions and other Stores, and the design of your present Cruize is to intercept as many of those Vessels and supplies as you possibly can.” The Fly and Wasp, if chased, were to run into some river or inlet on the New Jersey coast. Prizes were to be sent to Philadelphia, or into Egg Harbor, or any other safe place, as seemed most expedient. “You must be careful not to let any british frigate get between you and the land and then there’s no danger, for they cannot pursue you in shore and they have no boats or Tenders that can take you; besides, the country people will assist in driving them off shore, if they should attempt to follow you in . . . Altho’ we recommend your taking good care of your Vessel and people, yet we should deem it more praiseworthy in an officer to loose his vessel in a bold enterprise than to loose a good Prize by too timid a Conduct.” (Mar. Com. Letter Book, 42 (to Captain Warner of the Fly, November 1, 1776.) November 11 the committee wrote: “We have received intelligence that our enemies at New York are about to embarque 15,000 Men on board their Transports, but where they are bound remains to be found out. The Station assigned you makes it probable that we may best discover their destination by your means, for it will be impossible this fleet of Transports can get out of Sandy hook without your seeing them.

When you discover this fleet, watch their motions and the moment they get out to Sea and shape their course, send your boat on Shore with a Letter to be dispatched by express informing us what course they steer, how many sail they consist of, if you can ascertain their numbers, and how many Ships of war attend them . . . If this fleet steer to the Southward either the Fly or Wasp, whichever sails fastest, must precede the fleet, keeping in shore and ahead of them . . . The dullest sailer of the Fly or Wasp must follow after this fleet and watch their motions . . . In short we think you may by a spirited execution of these Orders prevent them from coming by Surprize on any part of this Continent, and be assured you cannot recommend yourself more effectually to our friendship. If you could find an opportunity of attacking and taking one of the fleet on their coming out, it might be the means of giving us ample intelligence.” (Mar. Com. Letter Book, 43 (to Warner.) This was the fleet which soon afterwards occupied Newport; it sailed from New York December 1, the transports passing through Long Island Sound, the larger men-of-war outside. About the end of November the Fly returned to Philadelphia and on December 21 was sent down the Delaware to watch some British vessels cruising off the capes. The Wasp continued on the New Jersey shore for a while and then watched these vessels from the outside. The Hornet cruised during the summer and in December was ordered to the West Indies; but she did not go, being in Christiana Creek and unable to get out through a British fleet in Delaware Bay (Am. Arch., V, i, 137, 1118, 1181, ii, 970, 1199, 1200, 1292, iii, 461, 507, 637, 904, 1148, 1175, 1176, 1213, 1331, 1332, 1458, 1484; Pennsylvania Gazette, October 16, 1776; Mar. Com. Letter Book. 17, 30, 38, 41, 42, 43, 47, 48 (August 23, October 10, 23, 30, November 1, 11, 29, December 14, 25, 1776).)

According to Admiral Howe’s letter of February 20, 1777, the British vessels employed in Delaware and Chesapeake Bays during 1776, some or all of them being stationed part of the time in one bay and part in the other and occasionally cruising off the capes, were the Roebuck of forty-four guns, the frigates Liverpool and Fowey, and the sloop of war Otter; while the frigate “Orpheus appears to have been rather appointed for the necessary and more general purpose of cruising between the port of New York and Entrance of the Delaware, than confined to the particular Guard of the last.” (Brit. Adm. Rec., A. D. 487, No. 24.)