Contents

Contents

Chapters

- Chapter 1: The Opening of Hostilities, 1775

- Chapter 2: Naval Administration and Organization

- Chapter 3: Washington’s Fleet, 1775 and 1776

- Chapter 4: The New Providence Expedition, 1776

- Chapter 5: Other Events in the Sea in 1776

- Chapter 6: Lake Champlain, 1776

- Chapter 7: Naval Operations in 1777

- Chapter 8: Foreign Relations, 1777

- Chapter 9: Naval Operations in 1778

- Chapter 10: European Waters in 1778

- Chapter 11: Naval Operations in 1779

- Chapter 12: The Penobscot Expedition, 1779

- Chapter 13: A Cruise Around the British Isles, 1779

- Chapter 14: Naval Operations in 1780

- Chapter 15: European Waters in 1780

- Chapter 16: Naval Operations in 1781

- Chapter 17: The End of the War, 1782 and 1783

- Chapter 18: Naval Prisoners

- Chapter 19: Naval Conditions of the Revolution

- Appendix

South Carolina and Georgia, far from the seat of the Continental government and from the headquarters of the army, were peculiarly exposed to attack, yet for more than two years after the unsuccessful attempt of the British to take Charleston in 1776, they were not seriously menaced. In December, 1778, however, the English got possession of Savannah, and during the next year they determined upon another effort to capture the whole lower South. Admiral D’Estaing spent more than half of 1779 in the West Indies, where, with the exception of the conquest of Grenada, he reaped little glory in his encounters with the British. Up to this time the actual assistance he had rendered to the American cause was slight and there was general dissatisfaction with the meagre results thus far derived from the French alliance. D’Estaing’s aid being now requested in frustrating the British designs on the South, he appeared off the coast of Georgia, September 1, 1779, with a powerful fleet, although he had been ordered back to France, and joined General Lincoln in an attempt to recapture Savannah. Through delay, however, the opportunity was lost and their assault when made was unsuccessful. D’Estaing then sailed for France and Lincoln fell back on Charleston. General Clinton sailed from New York for South Carolina late in December, 1779 (Mahan, 365-376; Narr. and Crit. Hist., vi, 519-524; Stevens, 1203, 1238, 1246, 1247, 2010, 2011, 2023; Almon, vii, 244-248, viii, 182, 298, ix, 65; Stopford-Sackville MSS., 146-149; Channing, iii, 300.)

The full extent of the benefit derived from the French alliance was not appreciated at that early day in America. Its effect on the British imagination and the potential weight of the French fleet, its mere presence on the ocean, were not inconsiderable. An intercepted letter from General Clinton to Lord George Germain, dated Savannah, January 30, 1780, captured on a British packet by an American privateer, gives a view of the military situation as seen by English eyes and discloses a state of mind not free from apprehension. Clinton seems to have been impressed by the strength of Washington’s army and of its position and devoted his energies before going South to strengthening the defenses of New York. “The violent demonstrations of the rebels,” he wrote, “which threatened a determined attack on the post at New York in conjunction with a large naval and land armament under Count d’Estaing, then directing itself against the garrison at Savannah, necessarily turned our whole endeavours to defeat so alarming a combina tion…. Not a moment was to be lost in such a critical conjuncture, for every moment was important and expected to come with the account of d’Estaing’s appearance before our harbour.” Washington not only had a superior position in the Highlands, but likewise along the shore to the east, where “every advantage of water was also in his power by the Sound and, under protection of the French fleet, exposed us to the most perplexing embarrassments. Assailable in so many points and every instant expecting d’Estaing, we had but time to look towards and take measures for our own defence and the occasion required us to put forward our best exertions. I do not reckon among the lesser misfortunes of the last year the operations of d’Estaing on the American coast, the vast relief thereby given to the Rebel trade and the injury which it brought upon our’s, the impression it carried home to the minds of the people, of our lost dominion of the sea, and the disposition of the French to give them every assistance reconcileable with the general objects of the war, to compleat our ruin on the Continent.” (Almon, x, 36, 37, reprinted from Pennsylvania Journal, April 8, 1780. See Channing, iii, 300, 301.)

Commodore Whipple’s squadron, consisting of the frigates Providence, Boston, and Queen of France, and the Ranger, arrived at Charleston December 23, 1779. An officer of the Providence wrote home: “On our arrival here we found our designs against the enemy frustrated, as they had not attempted nor is it probable they will attempt any thing against this town this season.” This was written January 8, 1780. Three days later he added: “Since writing the above, we have received an account that the enemy are building flat boats and making preparations for another expedition against this town, which they say is to commence as soon as their reinforcement arrives from New York. If they should attempt it, I believe it will terminate as much to their dishonour as their cause and actions deserve, as the town and river are well fortified.” (Independent Chronicle, February 24, 1780.) January 24, the Providence and Ranger went to sea for a short cruise. The same officer says: “On our way to Tybee in Georgia we captured 3 transports, a brig of 14 guns and two armed sloops, which were loaded with cloathing, some military stores, a few infantry, about forty light dragoons of Lord Cathcart’s legion, 7 or 8 officers, as many passengers, two horses, and military furniture for forty others, which they were obliged to throw overboard in some heavy gales on their passage. By these vessels we learn that 140 sail left New-York about 4 weeks before, under convoy of 6 or 7 ships of the line and several frigates, with troops destined for Savannah. Then we proceeded to Tybee, at the bar of which we saw a very considerable number of ships at anchor (five of them appeared to be above 36 guns) and a variety of smaller vessels, &c. The object of our voyage was to take some of their transports, that we might gain intelligence of their strength and make what discoveries we could with respect to their situation at Tybee; this being done we returned on Thursday [January 27]. The force of the enemy must be great, considering the number of vessels employed to transport them. Some say that Sir Henry Clinton commands in person, others Lord Cornwallis. Let it be who it may, I believe we shall have a pretty serious affair of it. There can be no doubt but their intention is to carry this town.” (Independent Chronicle, April 6, 1780.)

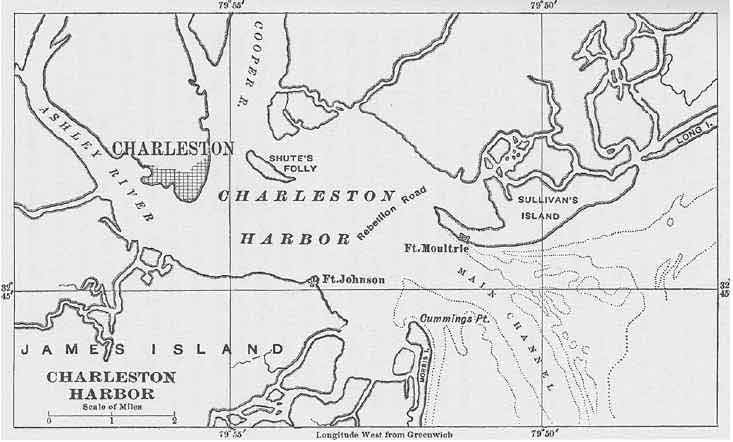

General Lincoln had about four thousand men at Charleston and the defenses of the city were strengthened as far as possible. General Clinton landed, February 11, south of the town and advanced upon it and invested it on the land side with ten thousand troops, while a British fleet under Admiral Arbuthnot, consisting of one fifty-gun ship, two forty-fours, and four thirty-twos, with smaller vessels, lay outside. On account of shallow water inside the bar, there was no practicable anchorage from which the American vessels could operate to advantage in defense of the channel and dispute the passage of the bar by the British. To inquiries of General Lincoln on this point a board of three naval captains and five pilots replied, February 27, that there was no anchorage within three miles of the bar. “In the place where the ships can be anchored, the bar cannot be covered or annoyed . . . Our opinion is that the ships can do most effectual service for the defence and security of the town, to act in conjunction with Fort Moultrie, which we think will best answer the purpose of the ships being sent here . . . Our reasons are that the channel is so narrow between the fort and the middle ground, that they may be moored so as to rake the channel and prevent the enemy’s troops being landed to annoy the fort.” (Tucker, 132-134.) The sinking of hulks or other obstructions in this narrow part of the channel was apparently not attempted. The Americans destroyed the lighthouse and ranges; also Fort Johnson, on the south side of the harbor, to prevent its falling into the hands of the enemy. This work was done by Captain Tucker of the Boston. In addition to the Continental ships the South Carolina navy furnished four vessels for the defense of Charleston, two of which, the Bricole, 44, and the Truite, 26, had been purchased from France; the other two were the General Moultrie, 20, and the Notre Dame, 16. Two French ships in the harbor, L’Aventure, 26, and Polacre, 16, also took part.

In his report of May 14 to the British Admiralty, after telling of landing the army, Admiral Arbuthnot says: “Preparations were next made for passing the squadron over Charles-town bar, where [at] high water spring tides there is only nineteen feet water. The guns, provision and water were taken out of the Renown, Roebuck, and Romulus, to lighten them, and we lay in that situation on the open coast in the winter season of the year, exposed to the insults of the enemy for sixteen days, before an opportunity offered of going into the harbour, which was effected without any accident on the 20th of March, notwithstanding the enemy’s galleys continually attempted to prevent our boats from sounding the channel . . . The rebel naval force . . . made an appearance of disputing the passage up the river at the narrow pass between Sullivan’s island and the middle ground, having moored their ships and galleys in a position to make a raking fire as we approached Fort Moultrie, but on the squadron arriving near the bar and anchoring on the inside, they abandoned that idea, retired to the town, and changed their plan of defence. The Bricole, Notre Dame, Queen of France, Truite and General Moultrie frigates, with several merchant ships, fitted with chevaux de frize on their decks, were sunk in the channel [of the Cooper River] between the town and Shute’s Folly; a boom was extended across, composed of cables, chains and spars, secured by the ship’s masts, and defended from the town by strong batteries of pimento logs, in which were mounted upwards of forty pieces of heavy cannon. . . . As soon as the army began to erect their batteries against the town I took the first favourable opportunity to pass Sullivan’s Island, upon which there is a strong fort and batteries, the chief defence of the harbour; accordingly I weighed at one o’clock on the 9th [of April] with the Roebuck, Richmond, Romulus, Blonde, Virginia, Raleigh, and Sandwich armed ship, the Renown bringing up the rear, and passing through a severe fire, anchored in about two hours under James Island, with the loss of twenty- seven seamen killed and wounded.” The total loss of the British fleet during the operations about Charleston was twenty-three killed and twenty-eight wounded. “The Richmond’s foretop-mast was shot away and the ships in general sustained damage in their masts and rigging; however, not materially in their hulls. But the Acetus transport, having on board a few naval stores, grounded within gun-shot of Sullivan’s Island and received so much damage that she was obliged to be abandoned and burnt.” (Almon, x, 45, 46.)

To prevent the British passing up the Cooper River the Americans sunk eleven vessels, including those mentioned in Arbuthnot’s report. Possibly these vessels, or others less valuable than some of them, might have been sunk to better advantage in the channel below Fort Moultrie, before the British crossed the bar. It might also with some reason be maintained that the squadron should have made a more vigorous defense of the channel at that point in conjunction with the fort; when by a lucky chance a few broadsides might have been able to cripple one or more of the British ships while they were passing through the narrowest places under a raking fire and in a disadvantageous position. Instead of that, the Americans retired up the river, which they attempted to block. The Ranger and two galleys were stationed above the obstructions while the guns and crews of the other naval vessels were sent ashore to reinforce the batteries. The British lines gradually drew closer to the town and American batteries on the north side of the Cooper River were taken. A bombardment began April 12. A few entries in the log of the Ranger tell the story of the closing days of the siege. April 15: “Enemy Kept up A Constant Cannonading.” May 7: “At 6 A.M. we could plainly discover that Our people had Evacuated Fort Moultrie & that the enemy had taken Possession of it; at 7 they hoisted their flag on it.” May 8: “This morning the Enemy sent in a Flag of truce, Which Caused a Total cessation of arms.” May 9: “At 9 P.M. the enemy began A most Desperate Cannonading, Throwing Shells, and firing of small arms, [which] Continued all night, with very little loss on our side.” May 10: “The enemy still Keeping A constant firing of Cannon, Throwing of Shells, Carcases, &c.” Here the record abruptly ends. Lincoln capitulated May 11 and Whipple’s squadron fell into the hands of the enemy. The Providence, Boston, and Ranger were taken into the British service, the two latter under the names Charlestown and Halifax. The officers were paroled and sent to Philadelphia (Tucker, ch. vii; Almon, x, 38-53; Andrew Sherburne, 26-29; Log of the Ranger; Stopford-Sackville MSS., 162 (Arbuthnot to Germain, May 15, 1780) ; Penn. Mag. Hist. and Biogr., April, 1891, Journal of Lieutenant Jennison; Mar. Com. Letter Book, 263, 264 (February 22, 1780); Boston Gazette, April 17, July 10, 1780 ; Independent Chronicle, May 11, 1780; Dawson, ch. lix; Narr. and Crit. Hist., vi, 524-527; Channing, iii, 317, 318.)

The frigate Trumbull, which was launched in 1776, remained in the Connecticut River where she was built until 1779, unable to pass over the bar at the mouth of the river. It is said that at the suggestion of Captain Hinman she was finally floated over by means of a number of casks full of water placed along her sides, held together by ropes passing under the keel and then pumped out, which lifted the ship sufficiently to carry her over the bar. She was taken to New London and fitted for sea. Meanwhile another frigate, the Bourbon, was being built on the Connecticut River. It was hoped that she would soon be at sea and Captain Thomas Read was ordered to command her, but for lack of money it was necessary to suspend work on her and she was not finished in time to take part in the war. Captain James Nicholson was appointed to command the Trumbull, September 20, 1779, but it was not until April 17, 1780, that cruising orders were sent to him. The Board of Admiralty, which had succeeded the Marine Committee in the administration of naval affairs, intended that the Trumbull should cruise in company with other Continental ships, but not with privateers; of such joint expeditions the board disapproved. Meanwhile, apparently awaiting an opportunity to get a number of vessels together, the orders of April 17 were repeated May 22 ; they prescribed a cruise for the Trumbull alone until the end of June (Papers New London Hist. Soc., IV, i, 47; Mar. Com. Letter Book, 238, 240, 241, 243, 252, 274, 276, 280, 285, 288 (September 20, October 6, 12, 21, December 18, 1779, April 7, 11, 17, May, 12, 22, 23, 1780)

The Trumbull sailed from New London late in May and had not been long at sea when she fell in with the British letter of marque Watt and was soon engaged in one of the hardest-fought naval actions of the war. In Nicholson’s account of the battle he says: “At half past ten in the morning of June [1st], lat. 35. N. long. 64 W. we discovered a sail from the mast-head and immediately handed all our sails, in order to keep ourselves undiscovered until she came nearer to us, she being to windward. At eleven we made her to be a large ship from the deck, coming down about three points upon our quarter; at half past eleven we thought she hauled a point more astern of us. We therefore made sail and hauled upon a wind towards her, upon which she came right down upon our beams; we then took in our small sails, hauled the courses up, hove the maintop-sail to the mast, got all clear for action, and waited for her.

“At half past eleven we filled the main-top (the ship being then about gun-shot to windward of us) in order to try her sailing, also that by her hauling up after us we might have an opportunity of discovering her broadside. She immediately got her main tack out and stood after us; we then observed she had thirteen ports of a side, exclusive of her briddle ports, and eight or ten on her quarter deck and forecastle. After a very short exhortation to my people they most chearfully agreed to fight her; at twelve we found we greatly outsailed her and got to windward of her; we therefore determined to take that advantage. Upon her observing our intention she edged away, fired three shot at us and hoisted British colours as a challenge; we immediately wore after her and hoisted British colours also. This we did in order to get peaceably alongside of her, upon which she made us a private signal and upon our not answering it she gave us the first broadside, we then being under British colours and about one hundred yards distant. We immediately hoisted the Continental colours and returned her a broadside, then about eighty yards distance, when a furious and close action commenced and continued for five glasses, no time of which we were more than eighty yards asunder and the greater part of the time not above fifty; at one time our yard-arms were almost enlocked. She set us twice on fire with her wads, as we did her once; she had difficulty in extinguishing her’s, being obliged to cut all her larboard quarter nettings away.

“At the expiration of the above time my first Lieutenant, after consulting and agreeing with the second, came aft to me and desired I would observe the situation of our masts and rigging, which were going over the side; therefore begged I would quit her before that happened, otherwise we should certainly be taken. I therefore most unwillingly left her, by standing on the same course we engaged on; I say unwillingly, as I am confident if our masts would have admitted of our laying half an hour longer alongside of her, she would have struck to us, her fire having almost ceased and her pumps both going. Upon our going ahead of her she steered about four points away from us. When about musquet shot asunder, we lost our main and mizen topmast and in spite of all our efforts we continued losing our masts until we had not one left but the foremast and that very badly wounded and sprung. Before night shut in we saw her lose her maintopmast. I was in hopes when I left her of being able to renew the action after securing my mast, but upon inquiry found so many of my people killed and wounded and my ship so much of a wreck in her masts and rigging, that it was impossible. We lost eight killed and thirty one wounded; amongst the former was one lieutenant, one midshipman, one serjeant of marines, and one quarter gunner; amongst the latter was one lieutenant, since dead, the captain of marines, the purser, the boatswain, two midshipmen, the cockswain, and my clerk, the rest were common men, nine of which in the whole are since dead. No people shewed more true spirit and gallantry than mine did; I had but one hundred and ninety-nine men when the action commenced, almost the whole of which, exclusive of the officers, were green country lads, many of them not clear of their sea-sickness, and I am well persuaded they suffered more in seeing the masts carried away than they did in the engagement.

“We plainly perceived the enemy throw many of his men overboard in the action, two in particular which were not quite dead; from the frequent cries of his wounded and the appearance of his hull, I am convinced he must have lost many more men than we did and suffered more in his hull. Our damage was most remarkable and unfortunate in our masts and rigging, which I must again say alone saved him; for the last half hour of the action I momently expected to see his colours down, but am of opinion he persevered from the appearance of our masts. You will perhaps conclude from the above that she was a British man of war, but I beg leave to assure you that it was not then, nor is it now my opinion; she appeared to me like a French East-Indiaman cut down. She fought a greater number of marines and more men in her tops than we did, the whole of which we either killed or drove below. She dismounted two of our guns and silenced two more; she fought four or six and thirty twelve pounders, we fought twenty-four twelve and six sixes. I beg leave to assure you that let her be what she would, either letter of marque or privateer, I give you my honour that was I to have my choice tomorrow, I would sooner fight any two-and-thirty gun frigate they have on the coast of America, than to fight that ship over again; not that I mean to degrade the British men of war, far be it from me, but I think she was more formidable and was better manned than they are in general.” (Almon, x, 225-227.)

Some further details are given in a letter of Gilbert Saltonstall, captain of marines on the Trumbull. “As soon as she discovered us she bore down for us. We got ready for action, at one o’clock began to engage, and continued without the least intermission for five glasses, within pistol shot. It is beyond my power to give an adequate idea of the carnage, slaughter, havock and destruction that ensued. Let your imagination do its best, it will fall short. We were literally cut all to pieces; not a shroud, stay, brace, bowling or any other of our rigging standing. Our main top-mast shot away, our fore, main, mizen, and jigger masts gone by the board, two of our quarter-deck guns disabled, thro’ our ensign 62 shot, our mizen 157, main-sail 560, foresail 180, our other sails in proportion. Not a yard in the ship but received one or more shot, six shot through her quarter above the quarter deck, four in the waste, our quarter, stern, and nettings full of langrage, grape and musket ball. We suffered more than we otherwise should on account of the ship that engaged us being a very dull sailer. Our ship being out of command, she kept on our starboard quarter the latter part of the engagement. After two and a half hours action she hauld her wind, her pumps going; we edged away, so that it fairly may be called a drawn battle.” (Independent Chronicle, July 6, 1780.)

In another letter, of June 19, Saltonstall says: “Our troubles ceased not with the engagement. The next day, the 2nd, it blew a heavy gale of wind, which soon carried away our main and mizen masts by the board, the fore topmast followed them and had it not been for the greatest exertions, our foremast must have gone also, it being wounded in many places, but by fishing and propping it was saved. . . . We remained in this situation till the next day, the 3rd, our men having got a little over the fatigue of the engagement and the duty of the ship; the gale abating we got up jury masts and made the best shift. In the night the gale increased again and continued from that time till we got soundings on George’s Banks in 45 fathoms of water the 11th instant. We got into Nantasket the 14th, the day following into the harbor.” (Papers New London Hist. Soc., IV, i, 55.)

The Watt, greatly shattered, got into New York June 11. The accounts of her force vary somewhat. She seems to have mounted twenty-six twelve-pounders and from six to ten sixes. Her crew was reported to number two hundred and fifty, but one New York paper made it one hundred and sixty-four. Her commander, Captain Coulthard, describing the action, says: ” Saw a large ship under the lee bow, bearing N. W. by W., distant about three or four miles; supposed her to be a rebel vessel bound to France and immediately bore down upon her. When she perceived we were standing for her she hauled up her courses and hove too. We then found her to be a frigate of 34 or 36 guns and full of men and immediately hoisted our colours and fired a gun; she at the same time hoisted Saint George’s colours and fired a gun to leeward. We then took her for one of his Majesty’s cruizing frigates and intended speaking to her, but as soon as she saw we were getting on her weather quarter, they filled their topsails and stood to the eastward. We then fired five guns to bring her to, but she having a clean bottom and we foul and a cargo in, could not come up with her. Therefore, finding it a folly to chace, fired two guns into her and wore ship to the westward; at the same time she fired one gun at us, loaded with grape shot and round, and wore after us. Perceiving this, we immediately hauled up our courses and hove too for her.

“She still kept English colours flying till she came within pistol shot on our weather quarter; she then hauled down English colours and hoisted rebel colours, upon which we instantly gave her three cheers and a broadside. She returned it and we came alongside one another and for above seven glasses engaged yard arm and yard arm; my officers and men behaved like true sons of Old England. While our braces were not shot away, we box-hauled our ship four different times and raked her through the stern, shot away her main topmast and main yard and shattered her hull, rigging and sails very much. At last all our braces and rigging were shot away and the two ships lay along-side of one another, right before the wind; she then shot a little ahead of us, got her foresail set and run. We gave her t’other broadside and stood after her; she could only return us two guns. Not having a standing shroud, stay or back- stay, our masts wounded through and through, our hull, rigging and sails cut to pieces, and being very leaky from a number of shot under water, only one pump fit to work, the other having been torn to pieces by a twelve pound shot, after chasing her for eight hours, lost sight and made the best of our way to this port. We had eleven men killed, two more died the next day, and seventy-nine wounded.” (Almon, x, 142, 143; Massachussetts Spy, August 17, 1780; Boston Gazette, June 5, 19, July 24, August 28, 1780; Independent Chronicle, July 6, September 7, 1780; Papers New London Hist. Soc., IV, i, 51-56; Williams, 273.)

The Board of Admiralty continued to develop plans for a cruise by a squadron under Nicholson, who was the senior captain of the navy. The Confederacy, Captain Harding, which had been temporarily repaired at Martinique after her dismasting and had returned to Philadelphia about May 1, the Deane, Captain Samuel Nicholson, brother of the commodore, and the Saratoga, a new eighteen-gun sloop of war commanded by Captain Young, were, with the Trumbull, to make up the squadron. These ships were all that remained of the Continental navy, in commission at this time, except the Alliance. The Deane had made a successful cruise early in the year, taking a number of prizes. She and the Saratoga were ready for sea in June, but the Confederacy and Trumbull were in need of extensive repairs. Nicholson received a Letter from the Board of Admiralty, dated June 30, congratulating him upon “the gallantry displayed in the Defence” of his ship in his recent action with the Watt and urging “exertions in Speedily refitting” her. The long-looked-for reinforcement from France, consisting of five thousand troops under General Rochambeau, sailed from Brest May 1, convoyed by seven ships of the line commanded by Admiral de Ternay, and arrived at Newport July 12; this place had been evacuated by the British in October, 1779. It was intended by Congress that the Continental squadron should keep a lookout for an expected second division of the French fleet from Brest and warn them of the situation of the British fleet, and should also cooperate with De Ternay; this was in accordance with the wish of General Washington, but no union of these forces took place. All the French ships were blockaded by the British – the second division in Brest, and De Ternay in Newport by a superior force under Arbuthnot, who had returned from Charleston (Mar. Com. Letter Book, 259, 262, 266, 281, 284, 285, 298, 312, 815, 322 (January 31, February 15, 28, May 2, 12, June 30, August 11, 14, 28, 1780) ; Pap. Cont. Congr., 78, 12, 5 (February 4, 1780), 37, 223, 287, 311 (April 11, August 1, 6, 1780); Boston Post, April 20, 1780; Boston Gazette, May 1, 1780; Mahan, 382, 383.)

The Mercury, a packet in the employ of Congress which had been stationed in Delaware Bay, set sail in August for Holland under the command of Captain Pickles, having on board as passenger Henry Laurens, who was sent on an important mission to the Dutch government. The Mercury was convoyed for a short distance by the Saratoga and early in September was captured by a British frigate off the Banks of Newfoundland. The dispatches, including a draft of a treaty with Holland, were thrown overboard, but unfortunately did not sink and were recovered by the British. Laurens was confined about a year in the Tower of London (Mar. Com. Letter Book, 295, 311, 315 (June 19, August 11, 14,1780); Pap. Cont. Congr., 37, 431 (July 18,1780); Stevens, 930, 931.)

Many instructions were issued for the movements of the Continental squadron. August 11, the Trumbull was ordered on a two weeks’ cruise off the coast, in a letter which required of Commodore Nicholson that “all such prizes as you may take and send into this port are to be directed to the care of the Board of Admiralty, the prizes which you may be Obliged through necessity to send into Other Ports you are to direct to the care of the Continental Agent of the district. You are always to Observe that you are to give the preference to this port as a place to which you are to direct your prizes when winds, weather and Other circumstances will admit of it without being more hazardous than elsewhere. The Deane and Saratoga will Sail in Company with you and under your Orders; you will therefore prepare and give to the Captains or commanding Officer of each of those Ships such instructions as may be necessary for regulating the Cruize . . . You will also when at the Capes employ some of your Crew in catching Fish, which will Afford a healthful variety of food to them and save your flesh Provisions. You are to see that the Ships company of the little fleet under your command frequently are disciplined in the exercise of the great Guns and Small Arms, to render them more expert in time of Battle, and that OEconomy, frugality, neatness and good Order are punctually Observed.” (Mar. Com. Letter Book, 312.) August 19, the Saratoga was ordered to sea with sealed instructions “of a Secret Committee of Conferrence with the Minister of France,” which the Board of Admiralty surmised might take her to the West Indies. On the 29th the Trumbull was ordered on a three weeks’ cruise on the Atlantic coast with the Deane, and two weeks later this cruise was extended and the Saratoga was to endeavor to join them. Renewed instructions as to cooperation with the French were included in nearly all the board’s letters. As late as August 31, the Confederacy was still unfit for active service, being “the only Continental frigate now within Harbour, but neither manned Or victualed for the Sea.” The Deane made a three weeks’ cruise off the coast of South Carolina in September, but “without taking anything worth naming,” according to Richard Langdon, son of the president of Harvard College, who was on board. This caused disappointment, for success had been depended upon “to equip three quarters of our navy, which is now in this river, viz: the Confederacy, Trumbull and Deane frigates.” (Independent Chronicle, January 25, 1781.) The Saratoga took four valuable prizes, at least one of which was more heavily armed than herself ; they were all recaptured, however. The ships were in port a large part of the time preparing for sea under difficulties which caused endless delay. These difficulties as might be expected were mostly financial and not only hindered repairs on the vessels in commission, but prevented the completion of those under construction, the frigate Bourbon in the Connecticut River and the seventy-four-gun ship America still on the stocks at Portsmouth. The Board of Admiralty appealed to the governors of the New England States and to other persons of influence for help, but at this period of the war money had become the scarcest of all commodities. William Vernon, of the Eastern Navy Board, writing, November 10, about naval matters to William Ellery, then a member of the Board of Admiralty, says that Captain Samuel Nicholson had recently “arrived from Phila. having leave of absence . . . to come to Boston, his younger Brother John Nicholson being appointed to the Command of his ship the Deane Frigate, which he is to resume the Command of at the end of her present Cruise; he further informs that all the Continental Ships were to sail from the Delaware in consequence. That it was reported, when their Cruise was up, they were to go into the Chesapeake to recruit their Stores and Men; this message he verily believes was agreed upon. Which if true we are extreem sorry to hear, not that we as a Board can receive any injury, on the contrary shall get clear of a great deal of Trouble and Fatigue, but are fearful the Public are in much danger of Looseing the small remains of their Navy, at least of their being rendered useless for a Time, as it certainly cannot be difficult for British ships of superior Force to block up if not Capture them; moreover if this should not be the case, can stores of every kind be supplied in Virginia or Maryland, can Men be obtained to Mann the Deane and Trumbul, whose Time must be expired at their Arrival in the Chesapeake ? Indeed we think they were entitled to their discharge upon their Arrival in the Delaware from their last Cruise; they certainly were shiped for a Cruise only, upon no other Terms have we at any Time been able to Mann our ships. If we do not keep faith with the Seamen, our expectations are at an end of even Manning the Ships. I speak in regard to the Trumbul and Deane; perhaps it may be otherwise with the Confederacy and Saratoga, they may be shiped upon the New invitation of Entering for 12 Months. I have given you these hints not officially, meerly as my private opinion and that of my Colleage and make no doubt they will have their proper weight with you and that upon your joining the board of Admiralty at Phila., will suggest to them what shall in your judgment appear consonant to the benefit and Interest of the Public.” (Publ. R. I. Hist. Soc., viii, 268.) Another matter taken up by the Board of Admiralty in 1780 was the systematic attempt to obtain, through navy boards and other agents, all the information possible as to the numbers, character, and movements of the British naval forces at all points between Newfoundland and the West Indies (Mar. Com. Letter Book, 265, 289, 290, 291, 294, 300, 303, 304, 308, 310, 312, 313, 314, 315, 317, 318, 319, 321, 322, 331 (February 22, May 30, June 16, July 7, 21, August 4, 11, 14, 19, 22, 29, 31, September 14,1780); Pap. Cont. Congr., 37, 265, 269, 273, 517 (July 21, November 6, 1780); Penn. Packet, October 24, 1780; Publ. R. I. Hist. Soc., viii, 264-269; Barney, 84-86.)

The Massachusetts navy, which had lost all of its vessels in commission in the ill-fated Penobscot expedition, was about this time reinforced by the largest and most powerful ship in the state service during the Revolution. This was the twenty-six-gun frigate Protector, which was built on the Merrimac River and launched in 1779, but not ready for sea until the spring of 1780. In December, 1779, she narrowly escaped destruction by a fire at the wharf where she was moored. March 21, 1780, the following action was taken by the Massachusetts General Court: “Whereas it is absolutely necessary to increase the Naval Force of this State to defend the Trade and Sea Coasts thereof, Therefore Resolved, that the Board of War be and they are hereby directed to procure and fit for the Sea with all possible dispatch Two Armed Vessels to carry from Twelve to Sixteen Guns each.” Under this and supplementary acts a ship called the Mars was purchased in April and another was built and named the Tartar; the latter, however, was not finished until 1782. Captain Williams was put in command of the Protector; among her midshipmen was Edward Preble, who afterwards became famous. In January it had been intended to send her to Europe, but in May, after having made a short cruise, Williams was ordered by the Board of War on another, as far east as the Banks of Newfoundland and south to the thirty-eighth parallel and to the track of vessels from the West Indies, meanwhile making occasional visits to the coast of Maine. Captain Sampson was appointed to command the Mars, and in June was ordered to Nantes for goods needed by the army; he sailed early in August. On June 22, the General Court expressed disapproval of robberies said to have been committed along the Nova Scotia shore by Massachusetts privateers and resolved that in the future privateers must give bonds for the abolition of such evils (Mass. Court Rec., March 15, 21, April 20, May 5, June 22; Mass. Archives, cli, 506, cliii, 320, 345; Massachusetts Mag., July, October, 1910; Amer. Hist. Rev., x, 69; Boston Post, April 20, 1780.)

On her cruise to the eastward the Protector fought a hard battle on the Banks of Newfoundland of which the captain gives an account in his journal. “Friday, June 9, 1780, wind W. S. W. At 7 A.M. saw a large ship to windward bearing down for us under English colours; she hauled up her courses in order for action. At 11 A.M. we came along-side of her under English colours, hail’d her; she answered from Jamaica. I shifted my colours & gave her a broadside. She soon returned us another. The action was heavy for near 3 glasses, when unfortunately she took fire and soon after blew up; got out our boats to save the men, took up 55 of them. Among them was the 3d mate and the only officer sav’d; the greatest part of them very much wounded and burnt. She was called the Admiral Duff, a large ship of 32 guns, commanded by Richard Stranger, from St. Kitts and St. Eustatia laden with sugar and tobacco, bound to London.” (Boston Gazette, July 24, 1780.) The Protector lost one killed and five wounded out of her complement of two hundred.

This event was narrated in greater detail many years later by Luther Little, a midshipman on the Protector and brother of the first lieutenant, George Little. The midshipman says that on the morning of the battle there was a fog and when it “lifted, saw large ship to windward under English colors, standing down before the wind for us, we being to leaward. Looked as large as a 74. Concluded she was not a frigate. All hands piped to quarters. Hammocks brought up and stuffed in the nettings, decks wet and sanded &c . . . We stood on under cruising sail. She tried to go ahead of us and then hove to under fighting sail. We showed English flag. She was preparing for action. We steered down across her stern & hauled up under her lee quarter, breeching our guns aft to bring them to bear. Our first It. hailed from the gangboard . . . Our capt. ordered broadside and colors changed. She replied with 3 cheers and a broadside. Being higher, they overshot us, cutting our rigging. A regular fight within pistol range. In a hf hour a cannon shot came thro’ our side, killing Mr. Scollay, a midshipman who commanded the 4th 12-pounder from the stem. His brains flew over my face and my gun, which was the third from the stern. In an hour all their topmen were kld by our marines, 60 in no. and all Americans. Our marines kld the man at their wheel & the ship came down on us, her cat-head staving in our quarter galley. We lashed their jib-boom to our main shrouds. Our marines firing into their port holes kept them from charging. We were ordered to board, but the lashing broke & we were ordered back. Their ship shooting alongside nearly locked our guns & we gave a broadside, wh. cut away her mizen mast and made gt havoc. Saw her sinking and her maintopgallantsail on fire, wh run down her rigging and caught a hogshead of cartridges under her quarter deck and blew it off. A charge of grape entered my port hole. One passed between my backbone and windpipe and one thro’ my jaw, lodging in the roof of my mouth & taking off a piece of my tongue, the other thro’ my upper lip, taking away part, and all my upper teeth. Was carried to cockpit; my gun was fired only once after. I had fired it 19 times. Thinking I was mortally wounded they dressed first those likelier to live. Heard the surgeon say ‘he will die.’ The Duff sunk, on fire, colors flying. Our boats had been injured, but were repaired as well as possible & sent to pick up the swimmers; saved 55, one half wounded. Then first It confided to me that many were drowned rather than be made captives. Some tried to jump from the boats. Our surgeons amputated limbs of 5 of them. One was sick with W. India fever and had floated out of his hammock between decks. The weather was warm and in less than 10 days 60 of our men had it. Among those saved were 2 American captains & their crews, prisoners on board the Duff. One of the Am. captains told us that Capt. Strang had hoped we were a Continental frigate, when he first saw us.” (Manuscript in Harvard College Library.) While cruising off Nova Scotia with a great deal of sickness on board, the Protector fell in with the Thames, a British frigate of thirty-two guns. After a running fight of several hours the Protector escaped. She returned to Boston August 15. In the fall she made another cruise, first running to the eastward and then to the West Indies (Mass. Archives, cliii, 385; Boston Gazette, July 17, 24, August 21, 1780; Adventures of Ebenezer Fox, ch. iv, v; Clark, i, 102,103; Sabine’s Life of Preble, ch. i.)

Captain Elisha Hart, of the private armed sloop Retaliation, ten guns and fifty men, wrote from New London, September 29, 1780, to Governor Trumbull of Connecticut, that he had sailed on the 22d along the south side of Long Island to Sandy Hook and towards the Narrows, in New York Harbor. Several sloops were seen coming down from New York. The Retaliation chased them and overhauled one that was standing for Staten Island. “I discovered She Had no Guns,” says Hart, “but appeared full of Men Elligantly Dressed. I then Supposed her to be a Pleasure Boat from the fleet, which I then Saw Lying In the Narrows and was within One League of them and in full View of the City and More than a League within the Guard Ships.” Captain Hart got out sweeps, came up fast on the chase and hailed her, but her commander was very suspicious and refused to come on board the Retaliation. “I then ordered Down my English Colours, Ran out my Bow Guns and Told him if He did not Come on Board I would Sink Him Immediately. He then Hove out his Boat and Come on Board. I Immediately Man’d the Prize and Took out the Prisoners.” They were forty-seven in number, including a captain, a lieutenant, and two sergeants; they were a captain’s guard, sent to relieve guard at the lighthouse. An armed sloop from near the guardship approached, but bore away upon the Retaliation’s heaving to for her. The prize was brought safely into New London (Trumbull MSS., xiii, 41 ; Continental Journal, October 5, 1780; Papers New London Hist. Soc., IV, i, 18.)

Alexander Murray, who was afterwards a lieutenant in the Continental navy, commanded the letter of marque Revenge in 1780; she carried eighteen six-pounders and fifty men and was fitted out at Baltimore for a voyage to Holland. Having collected a convoy of fifty sail in Chesapeake Bay, some of them armed, Murray attempted to get to sea, but upon the appearance of a squadron of British privateers, consisting of an eighteen-gun ship, a sixteen-gun brig, and three schooners, his convoy, with the exception of two vessels, deserted him and fled. The Revenge alone engaged the ship and brig with both broadsides, lying between them, and beat them both off after a hard-fought action of more than an hour. The two vessels with him kept the three schooners occupied until the convoy had time to escape into Hampton Roads. Murray returned to port to repair damages and then once more set sail. On the Banks of Newfoundland he captured a letter of marque brig. He pursued his voyage, but unluckily fell in with a large British fleet of men-of-war and transports, was chased by a frigate and captured. Not long afterwards Murray was exchanged (Clark, i, 117; Port Folio, May, 1814. For further accounts of privateering and prizes in 1780, see Boston Gazette, March 6, 20, May 1, July 3, 24, 31, September 4, November 6, 1780; Massachusetts Spy, August 17, 1780; Continental Journal, October 19, 1780; Penn. Gazette, July 19, 1780; London Post, May 1, August 4, 1780; Pickering MSS., xxxiii, 280; Almon, x, 55, 60, 265-267; Clark, i, 116,119; Virginia Hist. Register, July, 1853; Tucker, ch. viii; Papers New London Hist. Soc., IV, i, 16; R. I. Hist. Mag., July, 1884.)

A source of embarrassment to British naval administration during the war was jealousy and ill feeling among the officers of the navy. One instance was a bitter quarrel between Admirals Keppel and Palliser in 1778. Admiral Rodney came out to the West Indies early in 1780 and remained there most of the time until 1782. His relations with other officers seem seldom to have been pleasant, and lust of prize money interfered at times with the discharge of duty. His first exploit was an encounter with a French fleet under the Comte de Guichen, which led to contentions with his captains due to misunderstanding about signals. In September, Rodney went to New York for a short stay, arriving just in time to fall into a large amount of prize money, which came to him as senior officer on the station and would otherwise have gone to Admiral Arbuthnot. This occasioned a disagreeable quarrel between them. In a letter dated October 19, 1780, Rodney says to Arbuthnot: “I am honoured with your letter of the 16th Instant and am sorry that my Conduct has given you offence; none was intended on my part … It was not inclination or Choice that brought me to America; it was the Duty I owed my King and Country. I had flattered myself it would have met with your approbation. I am sorry it has not, but I own I have the vanity to think it will meet with His approbation whose it is the greatest Honor a Subject can receive. Your Anger at my partial interfering (as you term it) with the American War not a little surprises me. I came to Interfere in the American War, to Command by Sea in it and do my best Endeavours towards the putting an end thereto. I knew the Dignity of my own Rank and the power invested in me by the Commission I bear entitled me to take the supreme Command, which I ever shall do on every Station . . . unless I meet a Superior Officer … Your having detached the Raisonable to England without my knowledge, after you had received my orders to put your self under my command, is I believe unprecidented in the Annals of the British Navy.” (Brit. Adm m. Rec., A. D. Leeward Islands, vii.)

On October 30, Rodney wrote to the Admiralty: Vice Admiral Arbuthnot having taken it into his head to be highly Offended at me for doing what I thought my duty to His Majesty and the Public and acquainting me by letter dated the 16th Instant that he would remonstrate to their Lordships against my Conduct, I think it a duty I owe myself to transmit to the Admiralty Board Copies of My Orders and Letters to Mr. Arbuthnot with his answers to Me (His Superior officer), that their Lordships may Judge which of us has most cause to trouble them with Complaints. . . . That I have been extremely tender in issuing Orders to Vice Admiral Arbuthnot and been attentive towards paying him every respect due to his Rank, the inclos’d letters I am sure will convince their Lordships. If in his Answers to me his letters have not been penn’d with that Cordiality which ought to pass between Officers acting in the Public Service, I am sorry for him, they effect not Me. I am ashamed to mention what appears to Me the real cause and from whence Mr. Arbuthnot’s chagrene proceeds, but the proofs are so plain that Prize Money is the Occasion that I am under the necessity of transmitting them . . . On my arrival at New York I found it necessary . . . to give Mr. Arbuthnot Orders to put himself under My Command, not only for the better carrying on the Public Service, but likewise to prevent any Litigious Suits relative to Prize Money, which Mr. Arbuthnot had given me but too much reason to expect . . . I can solemnly assure their Lordships that I had not the least conception of any other Prize Money on the Coast of America but that which would be most honourably obtain’d by the destruction of the Enemy’s Ships of War and Privateers, but when Prize Money appear’d predominant in the mind of my Brother Officer, I was determin’d to have my Share of that Bounty so graciously bestow’d by His Majesty and the Public . . . I flatter’d myself I should have had the honour even of Mr. Arbuthnot’s approbation of my Conduct. I am sorry I have not, but if I am so happy as to meet with that of their Lordships, it will more than fully compensate.” (Brit. Adm. Rec., A. D. Leeward Ids., vii; Mahan, 377-382; Hannay, ii, 226-229, 244-251; Belcher, i, 293, 301, 302; Channing, iii, 824; Nav. Rec. Soc., iii, 1, 2. For Arbuthnot’s complaints against Rodney, see Brit. Adm. Rec., A. D. 486, September 30, October 29, 1780.) Rodney returned to the West Indies in December.