Contents

Contents

Quick facts

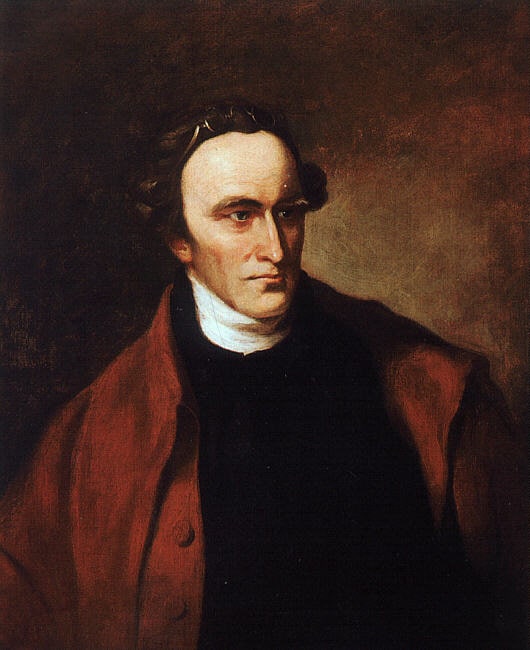

- Born: 29 May 1736 in Studley (in Hanover County), Virginia.

- Patrick Henry was a prominent figure in the American Revolution, best known for his declaration “Give me liberty, or give me death!” which he made during the Second Virginia Convention in 1775.

- He served as the first post-colonial Governor of Virginia and was a key advocate for American independence from Britain.

- Henry was a leading orator and a prominent voice in the anti-federalist movement, opposing the ratification of the U.S. Constitution in its original form.

- He played a significant role in the development of the Bill of Rights, insisting on the incorporation of amendments to safeguard individual liberties.

- Henry’s legal career was marked by his defense of individual rights, including his famous “Parson’s Cause” case, which challenged the British Crown’s authority over the colonies.

- He was influential in the establishment of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, which later inspired parts of the U.S. Constitution.

- Died: 6 June 1799 at his plantation, Red Hill, in Charlotte County, Virginia.</.li>

- Buried at Red Hill, Charlotte County, Virginia.

Biography

Patrick Henry, American statesman and orator, was born at Studley, Hanover County, Virginia, in 1736. He was the son of John Henry, a well-educated Scotsman, among whose relatives was the historian William Robertson, and who served in Virginia as county surveyor, colonel, and judge of a county court. His mother was from a family named Winston, of Welsh descent, noted for conversational and musical talent.

At the age of ten Patrick was making slow progress in the study of reading, writing, and arithmetic at a small country school, when his father became his tutor and taught him Latin, Greek, and mathematics for five years, but with limited success. His school days then terminated and he was employed as a store clerk for one year. During the next seven years he failed twice as a storekeeper and once as a farmer; in tandem he also acquired a taste for reading — of history especially — and he read and re-read the history of Greece and Rome, of England, and of her American colonies.

Poor but not discouraged, Henry resolved to be a lawyer, and after reading Coke upon Littleton and the Virginia laws for a few weeks only, he strongly impressed one of his examiners, and was admitted to the bar at the age of twenty-four, on condition that he spend more time in study before beginning to practice. He rapidly acquired a considerable practice, his fee books showing that for the first three years he charged fees in 1185 cases. In 1763 he delivered an popular speech in The Parson’s Cause

— a suit brought by the Reverend James Maury, in the Hanover County Court, to secure restitution for money considered by him to be outstanding from his salary (which was calculated at 16,000 pounds of tobacco) having been paid in money which was less than the current market price of tobacco. This speech, which, according to reports, was extremely radical and denied the right of the king to disallow acts of the colonial legislature, made Henry the idol of the common people of Virginia and procured for him an enormous practice.

In 1765 he was elected a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses, where he became in the same year the author of the Virginia Resolutions,

which were no less than a declaration of resistance to the Stamp Act and an assertion of the right of the colonies to legislate for themselves independently of the control of the British Parliament, and it gave a most powerful impetus to the American Revolution. In a speech urging their adoption are the often-quoted words: Tarquin and Caesar had each his Brutus, Charles the First his Cromwell, and George the Third

— here he was interrupted by cries of Treason — and George the Third may profit by their example! If this be treason, make the most of it.

Until 1775 he continued to sit in the House of Burgesses as a leader during that eventful period. He was prominent as a radical in all measures in opposition to the British government, and was a member of the first Virginia committee of correspondence.

In 1774 and 1775 he was a delegate to the First Continental Congress and the Second, serving on three of its most important committees: that on colonial trade and manufactures, that for drawing up an address to the king, and that for stating the rights of the colonies.

In 1775, in the second revolutionary convention of Virginia, Henry, regarding war as inevitable, presented resolutions for arming the Virginia militia. The more conservative members strongly opposed them as premature, whereupon Henry supported them in a speech, familiar to any American schoolchild, which closed with the words, Is life so dear or peace so sweet as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!

The resolutions were passed and their author was made chairman of the committee for which they provided. In addition, the chief command of the newly organized army was also given to him, but his military appointment required obedience to the Committee of Public Safety, and this body, largely dominated by Edmund Pendleton, so restrained him from active service that he resigned on 28 February 1776.

In the Virginia convention of 1776 he favored the postponement of a declaration of independence, until a firm union of the colonies and the friendship of France and Spain had been secured. In the same convention he served on the committee which drafted the first constitution for Virginia, and was elected governor of the state — to which office he was re-elected in 1777 and 1778, thus serving as long as the new constitution allowed any man to serve continuously. As governor he gave Washington able support and sent out an expedition into the Illinois country. In 1778 he was chosen a delegate to Congress, but declined to serve.

From 1780 to 1784 and from 1787 to 1790 he was a member of the Virginia Assembly; and from 1784 to 1786 was again governor. Until 1786 he was a leading advocate of a stronger central government but when chosen a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in Philadelphia, he had become cold to the cause and declined to serve. Moreover, in the state convention called to decide whether Virginia should ratify the Federal Constitution, he led the opposition, contending that the proposed Constitution, because of its centralizing character, was dangerous to the liberties of the country. This change of attitude is thought to have been due chiefly to his suspicion of the North aroused by John Jay’s proposal to surrender to Spain for twenty five or thirty years the navigation of the Mississippi.

From 1794 until his death he declined in succession the following offices: United States Senator (1794), Secretary of State in Washington’s cabinet (1795), Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court (1795), Governor of Virginia (1796), and envoy to France (1799). In 1799 he did agree to serve again in the State Assembly — where he wished to combat the Virginia Resolutions; he never took his seat; he died on his Red Hill estate in Charlotte County, Virginia, of that year.

Henry was twice married, first to Sarah Skelton and then to Dorothea Spotswood Dandridge, a grand-daughter of Governor Alexander Spotswood.