Contents

Contents

Pontiac’s Rebellion, also known as Pontiac’s War, was an uprising of the Native American population against settlers in the Thirteen Colonies, which lasted from 1763 to 1766.

Context and causes

From 1754 to 1763, the French and Indian War was fought in North America.

The war was fought between the British and the French, with various Native American tribes supporting either side.

Eventually, the British won the war, seizing the territory of New France – French settlements east of the Mississippi River.

Historically, the French had treated the Native Americans reasonably well, aiming to form alliances with the indigenous groups. However, the British were a lot harsher towards the native population, and once the war was won, they implemented policies that were much less accommodating to indigenous peoples compared to the French.

- British settlers began moving into tribal territories, without offering to buy the land or negotiating access.

- The British curtailed the flow of firearms and supplies to native tribes, breaking alliances established by French traders.

- British forces occupied former French forts without negotiating with local tribes.

- British officials like Jeffrey Amherst dismissed indigenous customs and failed to offer traditional gifts, which were previously essential to maintain alliances.

As a result, Native American tribes, especially those in the Great Lakes region, grew hostile towards the British.

Among the indigenous population, a prophet from the Lenape tribe named Neolin advocated a return to traditional indigenous ways, rejecting European influences, and inspiring resistance movements.

Native American tribes decided to drive British settlers off their land, under the leadership of a man named Pontiac, military leader of the Odawa people.

Summary of the Rebellion

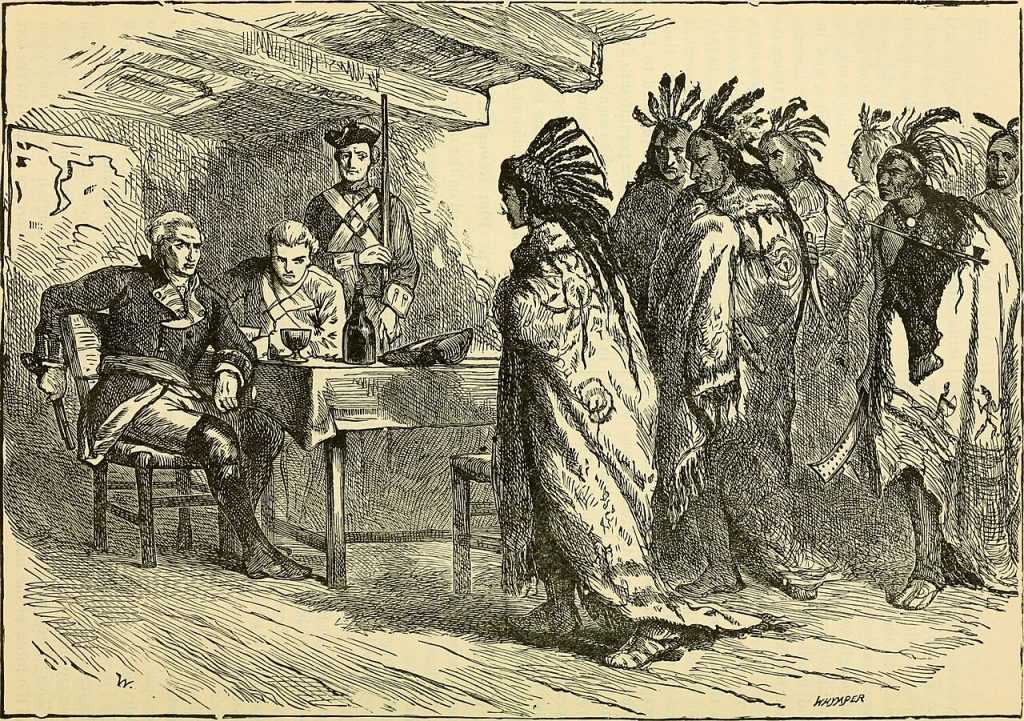

Pontiac’s Rebellion began with the siege of Fort Detroit, Michigan in May 1763, with as many as 900 warriors from numerous tribes joining the fighting.

However, the British defenders were forewarned about the attack, and fortified their position. The siege lasted for months but ultimately failed to capture the fort.

However, Pontiac and his allies were encouraged by the casualties they were able to inflict, and believed they could drive the British settlers from their land.

It is important for us, my brothers, that we exterminate from our lands this nation which seeks only to destroy us. You see as well as I that we can no longer supply our needs, as we have done from our brothers, the French…. Therefore, my brothers, we must all swear their destruction and wait no longer. Nothing prevents us; they are few in numbers, and we can accomplish it…

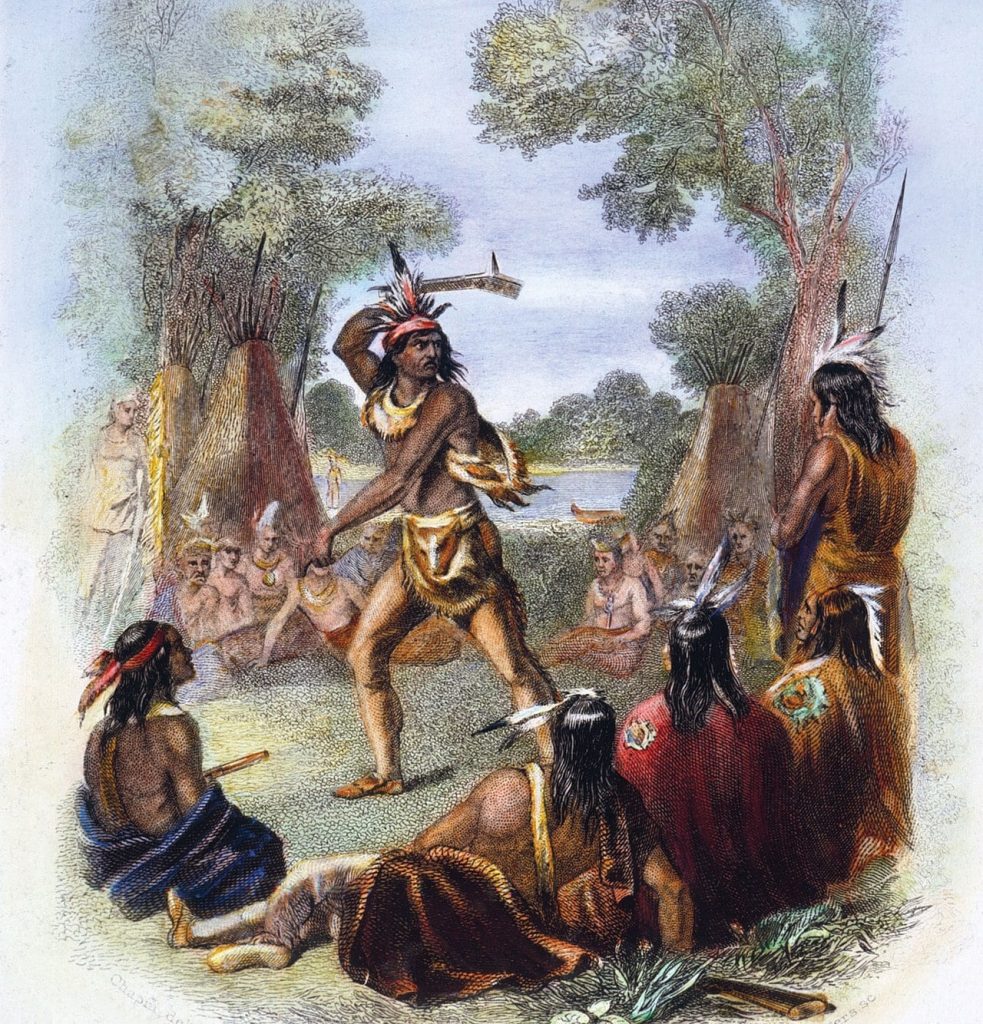

As a result, the rebellion spread rapidly across the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley regions. Tribes launched coordinated attacks on British forts and settlements, capturing key outposts such as Fort Sandusky, Fort Michilimackinac, and Fort Venango by the fall of 1763. By the end of that year, approximately half of the British forts in the region had fallen to indigenous forces.

Native American warriors killed or captured hundreds of settlers and soldiers during their raids on the forts, creating panic in frontier settlements.

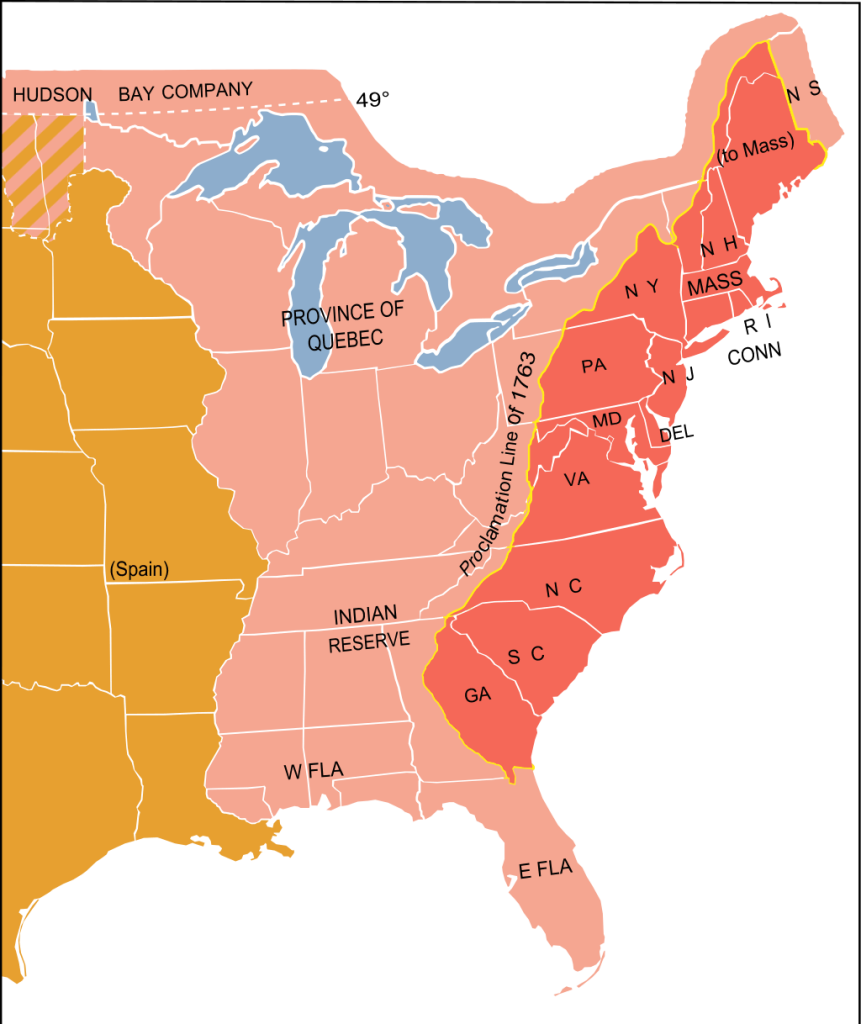

The British responded by issuing the Proclamation of 1763, which restricted westward expansion in the hope of appeasing the native tribes.

However, this measure upset the settlers, who wanted a stronger response against the rebellion, and wanted free reign to settle fertile lands west of the Appalachian Mountains.

In August 1763, the British resisted an indigenous siege at Fort Pitt. By this time, the settlers were getting desperate, employing tactics such as killing any Native Americans captured, to exterminate the population, and reduce their fighting force.

Smallpox was spreading inside the fort, so the British tried to use this against the Native Americans, giving them blankets infected with the disease, in an attempted act of biological warfare.

Historians disagree as to the success of this strategy, but it is commonly thought to have been successful, and responsible for a number of deaths.

Meanwhile, Native American raids continued, especially in Virginia – 1764 was a brutal year for settlers in the colony, with more than 100 killed in Native American raids.

However, by this time, the British began to regroup militarily, and recaptured a series of strategically important forts, before pursuing Native American tribes westward.

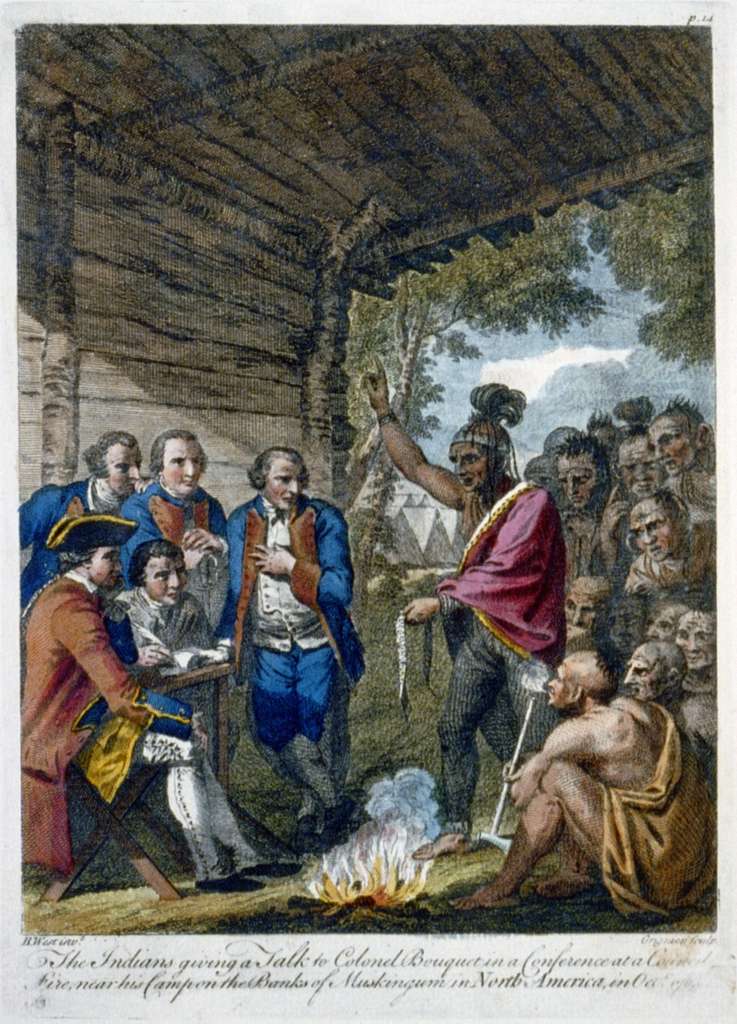

Pontiac’s forces, facing supply shortages, and unable to sustain prolonged resistance, began negotiating peace treaties. By the end of 1764, most of the fighting had stopped.

Pontiac himself formally made peace on July 25, 1766, traveling to New York to officially end his rebellion. From this point, his influence waned significantly, and he was assassinated by a Peoria warrior in 1769.

Significance and effects

Pontiac’s Rebellion underscored the deep tensions between indigenous peoples and European settlers over land, resources, and sovereignty in America.

It exposed flaws in British colonial policies, and set the stage for future conflicts between indigenous tribes and settlers, such as Tecumseh’s Confederacy during the War of 1812.

The war also led to increased colonial fear and hatred of indigenous groups, and heightened tensions between settlers and the British Crown.

Those living in the Thirteen Colonies resented the government’s half-hearted response to the conflict, and blamed them for the number of casualties that the Native forces were able to inflict.

They even set up vigilante groups, such as the Paxton Boys, who hunted down and murdered peaceful tribespeople, because they were unsatisfied with the British response, and also out of hatred of the Native Americans.

The Rebellion forced the British to create the Proclamation Line in 1763, in an attempt to limit tensions with Native populations, which led to even greater resentment from those living in the Thirteen Colonies.

At the time, people from many different social classes were eyeing up lands west of the Appalachian Mountains for farming and settlement.

For example, in colonies that relied on tobacco exports, such as Virginia, new farmland was in constant demand, as tobacco crops stripped the soil of its nutrients. As a result, the Proclamation Act upset everyone from small-scale subsidence farmers looking to support themselves, to large-scale plantation owners looking to expand their farming enterprises westwards.

Pontiac’s War also demonstrated the resilience and agency of indigenous peoples in defending their homelands.

However, colonial forces were stronger than the tribal warriors, leading Native populations to be increasingly driven westwards as the 18th century continued. The Proclamation Line was largely ignored due to poor enforcement, leading to constant encroachment by the colonists onto Native Indian land.