Contents

Contents

Quick facts

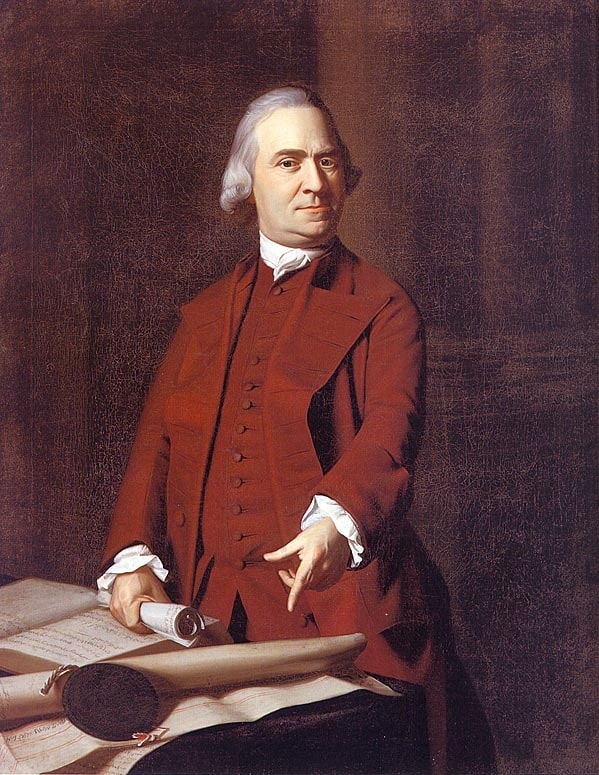

- Born: 27 September 1722 in Boston, Massachusetts.

- Samuel Adams was a Founding Father of the United States, known for his leading role in organizing the American Revolution’s early resistance movements against British policy.

- He was a key organizer of the Boston Tea Party, an iconic protest against British taxation that became a pivotal event leading to the Revolutionary War.

- Adams was a master of propaganda and used his skills to shape public opinion against British rule, making him one of the most influential political leaders of his time.

- He served in the Continental Congress, where he played a crucial role in rallying support for the American cause and in drafting the Articles of Confederation.

- As a politician in Massachusetts, Adams was instrumental in developing the colony’s revolutionary government and later served as its governor.

- He was a cousin of President John Adams and often collaborated with other key figures like John Hancock and Paul Revere in revolutionary activities.

- Died: 2 October 1803 in Boston, Massachusetts.

- Buried in the Granary Burial Ground in Boston, Massachusetts.

Biography

Samuel Adams, American statesman and, according to historian Joseph J. Ellis, the “Lenin of the American Revolution,” was born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1722. He was a second cousin to John Adams. His father, whose Christian name was also Samuel, was a wealthy and prominent citizen of Boston, who took an active part in the politics of the town, and was a member of the Caulker’s Club, from which the political term “caucus” is said to have originated. His mother was Mary Fifield.

Young Adams graduated from Harvard College in 1740, and three years later, on attaining the degree of A.M., chose for his thesis, “Whether it be Lawful to resist the Supreme Magistrate, if the Commonwealth cannot otherwise be preserved.” Which side he took, and how the argument proceeded, is not known, but the subject was a forecast of his career. He began the study of law in response to his father’s advice; he discontinued it in response to his mother’s disapproval. He repeatedly failed in business, notably as manager of a malt house, largely because of his incessant attention to politics; but in the Boston town meeting he became a conspicuous example of the efficiency of that institution for training in statecraft. He has indeed been called the “Man of the Town Meeting.”

About 1748 he began to take an important part in the affairs of the town, and became a leader in the debates of a political club which he was largely instrumental in organizing, and to whose weekly publication, the Public Advertiser, he contributed numerous articles. From 1756 to 1764 he was one of the Boston’s tax collectors. However in this office he was unsuccessful; his easy business methods resulted in heavy arrears.

Samuel Adams first came into wider prominence at the after the Stamp Act was passed in 1764, when as author of Boston’s instructions to its representatives in the general court of Massachusetts he urged strenuous opposition to taxation by act of parliament. The next year he was for the first time elected to the lower house of the general court, in which he served until 1974 (after 1766 as clerk). As the vigor and influence of James Otis declined, Adams took an increasingly prominent place in the revolutionary councils; and, contrary to the opinion of Otis and Benjamin Franklin, he declared that colonial representation in parliament was out of the question and advised against any form of compromise. Many of the Massachusetts revolutionary documents, including the famous “Massachusetts Resolves” and the circular letter to the legislatures of the other colonies are from his pen; but owing to the fact that he usually acted as clerk to the House of Representatives and to the several committees of which he was a member, documents were written by him which expressed the ideas of the committee as a whole. There can be no question, however, that Samuel Adams was one of the first, if not the first, American political leader to deny the legislative power of parliament and to desire and advocate separation from the mother country.

To promote the ends he had in view he suggested non-importation, instituted the Boston committees of correspondence, urged that a continental congress be called, sought out and introduced into public service such allies as John Hancock, Joseph Warren and Josiah Quincy, and wrote a vast number of articles for the newspapers, especially the Boston Gazette, over a multitude of signatures. He was, in fact, one of the most voluminous and influential political writers of his time. His style is clear, vigorous and epigrammatic; his arguments are characterized by strength of logic, and, like those of other patriots, are, as the dispute advances, based less on precedent and documentary authorities and more on “natural right.” Although he lacked oratorical fluency, his short speeches, like his writings, were forceful; his plain dress and unassuming ways helped to make him extremely popular with the common people, in whom he had a much greater faith than his cousin John. Above all, he was an eminently successful manager of men. Shrewd, wily, adroit, unfailingly tactful, an adept in all the arts of the politician, he is considered to have done more than any other one man, in the years immediately preceding the War of Independence, to mold and direct public opinion in his community.

Adams skillfully used the intense excitement which followed the Boston Massacre to secure the removal of the soldiers from the town to a fort in the harbor. He also managed the proceedings of the Boston Tea Party and later he was moderator of the convention of Massachusetts towns called to protest against the Boston Port Bill.

One of the objects of the military expedition sent by Governor Thomas Gage to Lexington and Concord on 18 – 19 April 1775, was the capture of John Hancock, and Adams, who was temporarily staying with him. When Gage issued his proclamation of pardon on 12 June he excepted these two, whose offenses, he said, were “of too flagitious a Nature to admit of any other Consideration than that of condign Punishment.”

As a delegate to both the First Continental Congress and the Second, from 1774 to 1781, Samuel Adams continued vigorously to oppose any concession to the British government; strove for harmony among the several colonies in the common cause; served on numerous committees, among them that to prepare a plan of confederation; and signed the Declaration of Independence. But he was rather a destructive than a constructive statesman, and though he shepherded the Articles of Confederation through Congress, his most important service was in organizing the forces of revolution before 1775.

In 1779 he was a member of the convention which framed the Constitution of Massachusetts that was adopted in 1780, and is still, with some amendments, the organic law of the state and one of the oldest fundamental laws in existence. He was one of the three members of the sub-committee which drafted it.

In 1788, Samuel Adams was a member of the Massachusetts convention to ratify the Constitution of the United States. When he first read it he was very much opposed to the consolidated government which it provided, but was induced to support it by resolutions which were passed at a mass meeting of Boston tradesmen — his firmest supporters — and by the suggestion that its ratification should be accompanied by amendments to supply the omission of a bill of rights. Without his aid it is probable that the constitution would not have been ratified by Massachusetts. From 1789 to 1794 Adams was Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts, and from 1794 to 1797 he was Governor.

After the formation of parties he became allied with the Democratic Republicans rather than with the Federalists. Samuel Adams was 81 when he died in 1803 in Boston.