Contents

Contents

Quick facts

- Born: February 1746 in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

- Tadeusz Kościuszko played a significant role in the American Revolution, contributing as a colonel in the Continental Army.

- He was responsible for fortifying West Point, New York, which later became the site of the United States Military Academy.

- After returning to Poland, Kościuszko led the Kościuszko Uprising in 1794 against Russian and Prussian occupation.

- Kościuszko was an advocate for the rights of serfs and sought to end serfdom in Poland.

- He was a close friend of Thomas Jefferson, with whom he shared ideals on human rights and freedom.

- In 1798 Congress granted $18,912 in back-pay to Kosciuszko for his role in the Revolutionary War. In his will, he authorizes his friend Thomas Jefferson

to use the money to purchase slaves, including his own, in order to free them. Jefferson neglects to do so. In 1826 when he dies, the money is still in trust, and Jefferson’s slaves are sold at auction.

- Despite his military and political involvements, Kościuszko maintained a deep interest in agriculture and engineering throughout his life.

- Died: 15 October 1817 in Solothurn, Switzerland.

Biography

Tadeusz Andrzej Bonawentura Kosciuszko, Polish soldier and statesman who participated in the American Revolution as well as the Polish–Russian War of 1792, was born in February 1746 in the village of Mereczowszczyno, Poland. The son of Ludwik Kosciuszko, sword-bearer of the palatinate of Brzesc, and Tekla Ratomska, he was educated at home before entering the corps of cadets in Warsaw.

His unusual ability and energy attracted the notice of Prince Adam Casimir Czartoryski, who used his influence to send Kosciuszko abroad in 1769 — at the expense of the state — to complete his military education. In Germany, Italy, and France he studied diligently, completing his course at Brest, where he learned fortification and naval tactics, returning to Poland in 1774 with the rank of Captain of Artillery.

In 1776, while engaged in teaching drawing and mathematics to the daughters of the Grand Hetman, Sosnowski of Sosnowica, he fell in love with the youngest of them, Ludwika. Not venturing to hope for the consent of her father, the lovers resolved to fly and be married privately. But before they could accomplish their design, the wooer was attacked by Sosnowski’s retainers; Kosciuszko defended himself valiantly till, covered with wounds, he was ejected from the house. Equally unfortunate was Kosciuszko’s wooing of Tekla Zurowska in 1791, the father of the lady in this case also refusing his consent.

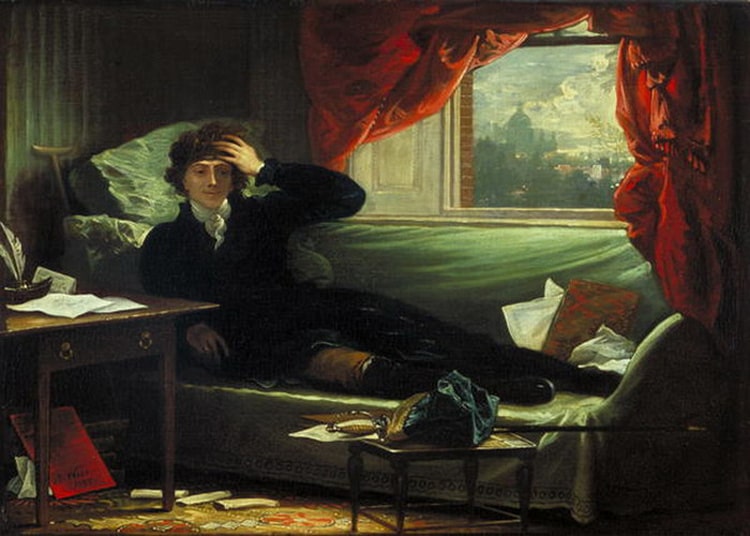

In the interval between these amorous episodes Kosciuszko won his spurs in the New World.

In 1776, he entered the army of the United States as a volunteer and brilliantly distinguished himself, especially during the operations about New York and at Yorktown. Washington promoted Kosciuszko to the rank of Colonel of Artillery and made him his adjutant. His humanity and charm of manner made Kosciuszko one the most popular of the American officers. In 1783 Kosciuszko was rewarded for his services and his devotion to the cause of American independence with the thanks of Congress, the privilege of American citizenship, a considerable annual pension with landed estates, and the rank of Brigadier General, which he retained in the Polish service.

Back home, Kosciuszko took a leading part in the war that followed the adoption by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth of the Constitution of 3 May 1791 — and the subsequent formation of the reactionary Confederation of Targowica. As the commander of a division under Prince Joseph Poniatowski, he distinguished himself at the Battle of Zielence and at Dubienka (1792). With only 4,000 men and 10 guns, he defended the line of the Bug for five days against the Russians, who had 18,000 men and 60 guns — subsequently retiring to Warsaw unmolested.

When the King acceded to the Targowicians, Kosciuszko, with many other Polish generals, threw up his commission and retired to Leipzig, which speedily became the center of the Polish emigration. In January 1793, provided with letters of introduction from the French agent Perandier, Kosciuszko went on a political mission to Paris to induce the revolutionary government to espouse the cause of Poland. In return for assistance, he promised to make the future government of Poland as close a copy of the French government as possible.

But the Jacobins, already intent on detaching Prussia from the anti-French coalition, had no serious intention of fighting Poland’s battles. The fact that Kosciuszko’s visit synchronized with the execution of King Louis XVI, subsequently gave the enemies of Poland a plausible pretext for accusing her of Jacobinism, and thus prejudicing Europe against her.

On his return to Leipzig, Kosciuszko was invited by the Polish insurgents to take the command of the national armies — with dictatorial power. He hesitated at first, well aware that a rising in the circumstances was premature. I will have nothing to do with Cossack raiding,

he replied; if war we have, it must be a regular war.

He also insisted that the war must be conducted on the model of the American War of Independence, and settled down in the neighborhood of Kraków to await events. When, however, he heard that the insurrection had already broken out, and that the Russian armies were concentrating to crush it, Kosciuszko hesitated no longer. He hastened to Kraków, which he reached on 23 March 1794.

On the following day his arms were consecrated according to ancient custom at the Church of the Capucins — giving the insurrection a religious sanction incompatible with Jacobinism. The same day, amidst a vast concourse of people in the marketplace, Kosciuszko took an oath of fidelity to the Polish nation and swore to wage war against the enemies of his country. At the same time, he protested that he would fight only for the independence and territorial integrity of Poland.

The insurrection had from the first a purely popular character. We find none of the great historic names of Poland in the lists of the original confederates. For the most part the confederates of Kosciuszko were small squires, traders, peasants, and men of low degree generally. Yet the comparatively few men who joined the movement sacrificed everything to it. To take a single instance, Karol Prozor sold the whole of his ancestral estates to contribute 1,000,000 thalers to the cause.

From 24 March to 1 April, Kosciuszko remained at Kraków organizing his forces. On 3 April at Raclawice, with 4,000 regulars and 2000 peasants armed only with scythes and pikes (and next to no artillery), he defeated the Russians, who had 5,000 veterans and 30 guns. This victory had an immense moral effect, and brought into the Polish camp crowds of waverers to what had at first seemed a desperate cause.

For the next two months Kosciuszko remained on the defensive near Sandomir. He dared not risk another engagement with the only army which Poland so far possessed, and he had neither money, officers, nor artillery. The country, harried incessantly during the last two years, was in a pitiable condition. There was nothing to feed the troops in the very provinces they occupied, and provisions had to be imported from Galicia. Money could only be obtained by such desperate expedients as the melting of the plate of the churches and monasteries, which was brought into Kosciuszko’s camp at Pinczow and subsequently coined at Warsaw, minus the royal effigy, with the inscription: Freedom, Integrity and Independence of the Republic, 1794.

Moreover, Poland was unprepared. Most of the regular troops were incorporated in the Russian army, from which it was very difficult to break away, and until these soldiers came in, Kosciuszko had principally to depend on the valor of his scythe-men. But in the month of April the situation improved. On the 17th, 2,000 Polish troops in Warsaw expelled the Russian garrison after days of street fighting, chiefly through the ability of General Mokronowski, and a provisional government was formed. Five days later Jakob Jasinski drove the Russians from Wilna.

By this time Kosciuszko’s forces had risen to 14,000, of whom 10,000 were regulars, and he was thus able to resume the offensive. He had carefully avoided doing anything to provoke Austria or Prussia. The former was described in his manifestoes as a potential friend; the latter he never alluded to as an enemy. Remember,

he wrote, that the only war we have upon our hands is war to the death against the Muscovite tyranny.

Nevertheless, Austria remained suspicious and obstructive; and the Prussians, while professing neutrality, very speedily effected a conjunction with the Russian forces. Misled by the treacherous assurances of Frederick William’s ministers, Kosciuszko never anticipated this and on 4 June he marched against General Denisov. He encountered the enemy on 5 June at Szczekociny when he discovered that his 14,000 men were vastly outnumbered by the combined forces of Russia and Prussia, numbering 25,000 men.

Yet the Poles acquitted themselves manfully; at dusk they retreated in perfect order to Warsaw, unpursued. But their losses had been terrible. Of the six Polish generals present, three, whose loss proved to be irreparable, were slain, and two of the others were seriously wounded. A week later another Polish division was defeated at Kholm. Kraków was taken by the Prussians on the 22 June and the mob at Warsaw broke into the jails and murdered the political prisoners in cold blood. Kosciuszko summarily punished the ringleaders of the massacres and had 10,000 of the rank and file drafted into his camp, which measures had a quieting effect.

But now dissensions broke out among the members of the Polish government, which required all the tact of Kosciuszko to restore order amidst this chaos of suspicions and recriminations. At the same time, he had need of all his ability and resources to meet the external foes of Poland.

On 9 July 1794, Warsaw was invaded by Frederick William of Prussia with an army of 25,000 men and 179 guns — along with the Russian General Fersen with 16,000 men and 74 guns. A third force of 11,000 occupied the right bank of the Vistula. Kosciuszko, for the defense of the city and its outlying fortifications, could dispose of 35,000 men, of whom 10,000 were regulars. But the position, defended by 200 inferior guns, was still a strong one, and the valor of the Poles and the engineering skill of Kosciuszko, who was now in his element, frustrated all the efforts of the enemy. Two unsuccessful assaults were made upon the Polish positions on the 26 August and 1 September; on the 6th, the Prussians, alarmed by the progress of the Polish arms in Great Poland — where Jan Henryk Dabrowski captured the Prussian fortress of Bydogoszcz and compelled General Schwerin with his 20,000 men to retire upon Kalisz — raised the siege.

Elsewhere, after a brief triumph, the Poles were everywhere thrashed. Suvarov, after driving them before him out of Lithuania, was advancing by forced marches upon Warsaw. Even now, however, the situation was not desperate, for the Polish forces were still numerically superior to the Russian. But the Polish generals proved unequal to carrying out the plans of the dictator; they allowed themselves to be beaten in detail and could not prevent the Suvarov and Fersen joining forces. Kosciuszko himself, relying on the support of Poninski’s division, attacked Fersen at Maciejowice on 10 October. But Poninski never appeared, and after a bloody encounter, the Polish army of 7,000 was almost annihilated by the 16,000 Russians. Kosciuszko, seriously wounded and insensible, was made a prisoner on the field of battle.

Kosciuszko was conveyed to Russia. There he remained until the death of Catherine the Great and the accession of her son, Paul, in 1796.

On his return on 19 December 1796, he paid a second visit to America, living in Philadelphia until May 1798, when he went to Paris, where Napoleon earnestly invited his cooperation against the Allies. But he refused to draw his sword unless the First Consul undertook to give the restoration of Poland a leading place in his plans; and to this, as he no doubt foresaw, Bonaparte would not consent.

Again and again, he received offers of high commands in the French army, but he kept aloof from public life in his house at Berville (near Paris), where the Emperor Alexander visited him in 1814. At the Congress of Vienna his importunities on behalf of Poland finally wearied Alexander, who preferred to follow the counsels of Czartoryski. Kosciuszko lived the remainder of his life retired to Solothurn, Switzerland, where he lived with his friend Franz Zeltner.

Shortly before his death on 15 October 1817, Kosciuszko emancipated his serfs, insisting only on the maintenance of schools on the liberated estates. His remains were carried to Kraków and buried in the cathedral; and the people, reviving an ancient custom, raised a huge mound to his memory near the city.

Kosciuszko was essentially a democrat, but a democrat of the school of Jefferson and Lafayette. He maintained that the republic could only be regenerated on the basis of absolute liberty and equality before the law; but in this respect he was far in advance of his age, and the aristocratic prejudices of his countrymen compelled him to resort to half measures.