Contents

Contents

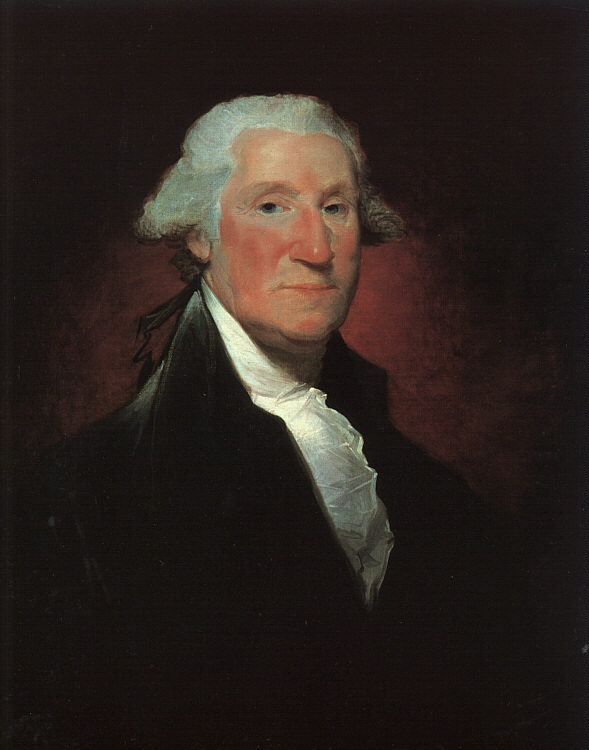

Altogether, Stuart painted Washington a total of three times, and yet there are literally scores, perhaps hundreds, of genuine, original Stuart portraits of him, and probably ten times that number of forgeries, some of which have become almost as famous as the real McCoy.

Paradoxical, you say? The explanation is long, so you may want to take a break here to get some chips and salsa before you read on. It will also, as you’ll see, give you a glimpse into the human side of both Stuart and Washington that your history books won’t give you.

Even before he met Stuart, Washington had been besieged by painters for years. During the making of his first portrait he had rebelled at the drudgery. “Inclination having yielded to importunity,” he had moaned in 1772, “I am now, contrary to all expectation, under the hands of Mr. [C. W.] Peale, but in so grave, so sullen a mood, and now and then under the influence of Morpheus when some critical strokes are making, that I fancy the skill of this gentleman’s pencil will be put to it in describing to the world what manner of man I am.”

In 1785, when he was submitting to the efforts of the English artist Robert Edge Pine, Washington wrote: “In for a penny, in for a pound is an old adage. I am so hackneyed to the touches of the painter’s pencil that I am now altogether at their beck, and sit like Patience on a monument, whilst they are delineating the lines of my face. It is a proof, among many other, of what habit and custom can effect. At first I was as impatient at the request, and as restive under the operation, as a colt is of the saddle. The next time I submitted very reluctantly, but with less flouncing; now, no dray moves more readily to the thrill than I do to the painter’s chair.”

When Stuart undertook his first Washington portrait in September 1795, he had no interest in depicting “Patience on a monument.” A skilled conversationalist, he relied on keeping the faces of his sitters animated by talking to them about their interests. “To military men,” a biographer tells us, “he spoke of battles by sea and land; with the statesman on Hume’s and Gibbon’s histories; with the lawyer on jurisprudence or remarkable criminal trials; with the merchant in his way; with the man of leisure in his way; with the ladies in all ways. When putting the rich farmer on the canvas, he would go along with him from seed to harvest time; he would descant on the nice points of horse, ox, cow, sheep, or pig, and surprise him with his just remarks in the progress of making cheese and butter, or astonish him with his profound knowledge of manures…. He had wit at will, always ample, sometimes redundant.”

Stuart complained that the moment Washington started to sit, “an apathy seemed to seize him, and a vacuity spread over his countenance most appalling to paint.” Stuart remarked: “Now, sir, you must let me forget that you are General Washington and that I am Stuart the painter.” “Mr. Stuart,” Washington replied politely, “need never feel the need of forgetting who he is, or who General Washington is.”

Stuart resolved “to awaken the heroic spirit in him by talking of battles.” The General looked up in surprise for a moment and then sank back into his boredom, for he had no intention of discussing military tactics with an artist.

On only one recorded occasion did the painter strike a spark from the General. As Stuart was allowing his tongue to idle on, no longer in hopes of rousing his sitter, but merely to keep the silence down, he launched on an old and hoary joke. He told the President how James II, on a journey through England to gain popularity, arrived in a town where the Mayor, who was a baker, was so frightened that he forgot his speech of welcome and stood there stammering. A friend jogged the Mayor’s elbow and whispered: “Hold up your head and look like a man.” When Stuart told how the flustered baker had repeated this admonition to the King, Washington’s stern face unbelievably broke into a smile. But before Stuart could lift his brush, the smile was gone.

According to Trumbull, “Mr. Stuart’s conversation could not interest Washington; he had no topic fitted for his character; the President did not relish his manners. When he sat to me, he was at his ease.”

While he was painting Washington, Charles Willson Peale, the doting patriarch of a large family of painters, also secured a promise of sittings. He laid a trap for the President. Once Washington was well seated before his easel, the door opened noiselessly. James, Rembrandt, and Raphaelle Peale tiptoed in one by one and put up their easels. “I looked in to see how the old gentleman was getting on with the picture,” Stuart later told his pupil John Neagle, “and to my astonishment I found the General surrounded by the whole family. They were peeling him, sir. As I went away, I met Mrs. Washington. ‘Madam,’ said I, ‘the General’s in a perilous situation. He is beset, madam. No less than five upon him at once. One aims at his eye; another at his nose; an other is busy with his hair; his mouth is attacked by the fourth; and the fifth has him by the button. In short, madam, there are five painters at him, and you who know how much he suffered when only attended by one, can judge of the horrors of his situation’ ”

Stuart had his own problems painting him for the first time. “There were features in his face totally different from what I had observed in any other human being. The sockets of the eyes, for instance, were larger than what I ever met with before, and the upper part of the nose broader. All his features were indicative of the strongest passions; yet like Socrates his judgment and self-command made him appear a man of different cast in the eyes of the world.”

Once the first picture was finished, Stuart took advantage of the financial opportunities it offered. Keeping possession of the original, so that no one else could make and sell copies, he himself made some fifteen copies which he sold for substantial sums. These canvases are known as the Vaughan type, since the first to be sold was to Samuel Vaughan, a wealthy merchant.

While turning out his Vaughan portraits, Stuart agitated for another chance to paint the President. In April 1796 his opportunity came through Mr. and Mrs. William Bingham, who persuaded Washington to stand for a full length they wished to give the famous British Whig, Lord Lansdowne. “It is notorious,” writes Washington’s adopted son, G. W. P. Custis, “that it was only by hard begging that Mr. Bingham obtained the sitting.” “Sir,” Washington wrote Stuart, on April 11, 1796, “I am under promise to Mrs. Bingham to sit for you tomorrow at nine o’clock, and wishing to know if it would be convenient for you that I should do so, and whether it would be at your house (as she talked of the State House), I send this note to you to seek information.”

Stuart began with the background, and painted it with the help of several assistants. It, and the pose, were copied from a portrait of a French clergyman of the 1600s. When you see the picture, you become vaguely aware that something about it doesn’t quite fit, and you’re right. The proportions are wrong. Washington was six foot, three and one-half inches tall (in his lifetime, he was known to be tall, but the only known time he was measured was post-mortem, for his casket). Stuart used a friend who was five foot six as a model for the body, arms and legs, and the outstretched hand belongs to Stuart himself. Thus prepared, Stuart was ready for the main subject.

When Stuart set up his easel, Washington appeared before it wearing a set of false teeth that pulled the lower part of his face out of shape. They fitted so badly that he used them for only a short time, but it was the time of the Lansdowne portrait. Not only did the distorted mouth bother Stuart; he was puzzled how to make the General’s figure look heroic. He complained that Washington’s “shoulders were high and narrow, his hands and feet remarkably large. He had aldermanic proportions, and this defect was increased by the form of the vest of that day.”

Created for money in opposition to the esthetic convictions of the artist and his assistants, the Lansdowne Washington (above) was far from a masterpiece. However, the heroic representation of so great a man by so famous a painter appealed to people who wished to have an obvious status symbol to show off to their friends. Stuart received many orders for copies, and since his usual pack of creditors was snapping at his heels, he accepted gladly.

Before sailing to France as American minister, General Charles Cotesworth Pinckney paid Stuart five hundred dollars for a Lansdowne copy to grace the embassy in Paris; it was never delivered. Timothy Pickering, United States Senator and former Secretary of State, wondered in 1804 whether the picture had ever been painted: “If it was, I think Stuart must have parted with it, intending doubtless to paint another for General Pinckney; but not having done it, gives no answer to his letters, because the explanation cannot be a pleasant one.” William Bingham sent Stuart’s original full length of Washington to Lord Lansdowne on October 29, 1796.

Hoping to “rescue myself from pecuniary embarrassment and to provide for a numerous family at the close of an anxious life” by having the picture reproduced for the world market by an expert English engraver, Stuart, so he always insisted, had asked Bingham to agree that no unauthorized copy be made. Bingham agreed verbally, but did not keep his agreement; the richest man in Philadelphia preferred to endanger the property of the impoverished artist rather than cheapen his gift by attaching strings. As a result, in all innocence of the agreement Lord Lansdowne gave James Heath of London permission to reproduce the picture, remarking that Stuart would certainly be gratified at having his work engraved by an artist of such distinguished ability.

Later, after Stuart told Bingham that he had commissioned Benjamin West of London to find a suitable engraver, the banker finally acted, but even then only indirectly. On June 10, 1787 he wrote Rufus King, the American Ambassador in London, asking him to mention to Lansdowne Stuart’s anxiety lest the picture be pirated. But much of a year had passed and the damage was already done.

When he learned of the unauthorized engraving, Stuart wrote Lansdowne a courteous request for an explanation – what reply he received is not known – and called on Bingham in a fury. The banker, so the painter told his friends, asked whether he had any proof in writing of a promise to preserve the copyright. The artist, of course, had nothing in writing, for it had never occurred to him not to trust Bingham’s word. He stamped out of the office, refusing to finish a picture of Mrs. Bingham he was painting, and thus cutting himself off forever from Philadelphia’s leading social arbiters and their friends.

The engraving was a most inferior one, and on every example the author of the original was given as “Gabriel Stuart.” “They will make an angel of me despite myself,” Stuart would say. but before his creditors had time to laugh he would be off on an impassioned complaint that he had never made a cent from the print, although it was an international best seller. That he had violated his esthetic convictions to produce the best seller only made the upshot more bitter. Efforts to find redress at law came to nothing. His daughters remembered how, as an old man, he would pace back and forth, gesticulating and muttering oaths, when the grievance came back to his memory. Indeed, he grew to blame all the financial difficulties that his improvidence had created on this one flagrant injustice.

Faced with such an attitude, Stuart carried his artistic arrogance to an extreme. After General Knox, Washington’s first Secretary of War, had offended him, he used the General’s portrait as the door for his pig sty. He refused to continue the picture of anyone who dared criticize the smallest detail; he would ring for his man and send the canvas up to the attic. Nor could all the tears of a lady who needed a Stuart to enhance her social position make him change his mind. When “a gentleman of estimable character and no small consequence in his own eyes” objected that Stuart’s portrait of the rich but homely widow he had married did not make her beautiful, the artist cried: “What damned business is this of a portrait painter! You bring him a potato and expect he will paint a peach.”

Trott, the miniaturist, found him one day in a great fury. “That picture,” he shouted, “has just been returned to me with the grievous complaint that the cravat is too coarse! Now, sir, I am determined to buy a piece of the finest texture, have it glued on the part that offends their exquisite judgment, and send it back.” Once he delineated a handsome woman who was a great talker. When the picture was almost done, she looked at it and exclaimed: “Why, Mr. Stuart, you have painted me with my mouth open!” He replied: “Madam, your mouth is always open” and refused to finish the picture.

Shortly after completing the Lansdowne portrait, he moved to Germantown, a suburb of Philadelphia, where he became even more consumed by drink and more contentious. “He has the appearance, an acquaintance wrote, of a man who is attached to drinking, as his face is bloated and red.” He created three hundred dollars worth of portraits for a wine merchant whose taste for pictures was as strong as his own for Madeira, but found, when they balanced accounts, that he still owed two hundred dollars.

In February 1801 Stuart wished immediate payment for a Washington portrait commissioned by the State of Connecticut. An installment, he explained, was due on the “purchase of a small farm for my family.” Once more dreaming of solace in rural quiet, he invested the proceeds from five Lansdownes of Washington and twenty smaller pictures in a property near Pottsgrove, Pennsylvania, which he stocked with imported Durham cows. He sent out the money as fast as he received it, and neglected to take receipts. When the man with whom he had been dealing died, there was no evidence that he had ever paid a dollar. As a result, he lost the whole sum, $3,442. He could never remember whether pictures had been paid for, and sometimes enraged sitters by demanding his fee twice, or amazed them by refusing sums due him.

Yet he kept his reputation as the greatest painter in America. When Mrs. Washington wanted a picture of the President for herself, she persuaded her unwilling husband to submit a third time to Stuart’s brush and company. In the stone barn in Germantown he used as a studio, the painter waited anxiously for Washington to ride out for the first sitting, and sighed with relief when he saw that the President’s new false teeth did not distort his face so much as the old. Washington entered the barn with cold courtesy, sat down in the chair Stuart had provided, and clamped his face into the rigid expression he saved for portrait-painters. Stuart plunged into his fund of anecdote, but the face did not relax.

When Stuart looked up from his canvas after a while, his heart almost stopped beating; Washington’s face bore a pleasant expression. It lasted only a few seconds, but by seemingly nonchalant questions Stuart found out what had put it there; the General had seen a noble horse gallop by the window. Instantly Stuart commented on a local horse race; Washington made an animated answer and his face came alive. Then Stuart ransacked his mind for all he knew about horses, and soon the two men were actually talking. Stuart’s brush flew merrily in rhythm with his tongue. The conversation moved on to farming, a subject it had never occurred to Stuart to discuss with the Commander-in-Chief, and again Washington was interested.

Not completely interested, however. Before the picture was finished, the President worked out a way to make the sittings bearable; he brought with him to the studio friends with whom he liked to talk: General Knox (with whom Stuart had not yet fought); the pretty Harriet Chew. They would keep his face alive, he dryly explained. Stuart at last saw the genial side of the hero, and he happened on an expedient to make the hero look imperious, as if he were commanding an army – all Stuart had to do was to be late for a sitting.

Stuart was delighted with the resulting picture. Although Washington had agreed to sit only so that his wife might have the portrait, Stuart determined to keep it; he felt he could make a fortune from copying it for all comers. He completed the face but not the background, and whenever Mrs. Washington sent for the picture, he apologetically explained that it was not finished. Finally, she came in person, bringing the President along. When he fobbed her off with the same transparent excuse, she walked out in a huff. Stuart always insisted that Washington had not followed at once, but had whispered in his ear that he was to keep the portrait as long as he wished, since it was of such great advantage to him. An intimate of Washington’s circle, however, reports that the President was very annoyed with Stuart; that he came several times to the studio, demanding the picture, and finally said in a curt manner: “Well, Mr. Stuart, I will not call again for this portrait. When it is finished, send it to me.” The picture was never finished. Mrs. Washington had to put up with a copy which she told her friends was not a good likeness.

This third picture of Washington is known as the Athenaeum portrait, since it eventually came into the possession of the Boston Athenaeum. Whether it resembled the President or not, one thing is certain – it was immensely popular in its own day, and is the only representation of the father of their country which most modern Americans know. Stuart himself ceased using his other two portraits; he destroyed, or so he said, the original of the Vaughan type, and topped his copies of the Lansdowne full-length with the Athenaeum head. He kept the canvas by him all his life and, whenever his creditors became too importunate, dashed off copies to which he gaily referred as his “hundred dollar bills.” He sold more than seventy that we know of, and possibly more.

Success breeds imitation, and copycat artists were many and prolific. Stuart ended up suing one merchant who was importing copies of the Athenaeum Washington from China. One of the most prolific and talented forgers was named Winstanley. It is said that Winstanley traveled to Germantown and presented himself at Stuarts home, actually expecting to be praised for his artistic abilities and industriousness in making a living by copying Stuart’s work. Not surprisingly, Stuart threatened to throw him through a window if he didn’t leave voluntarily.

Stuart claimed the Washington that adorned the White House was one of Winstanley’s forgeries. However, if it was, the claim was ineffectual. When the English took the capital in 1814, Dolly Madison, the President’s wife, commanded a servant to save or destroy “the portrait of President Washington, the eagles which ornament the drawing-room, and the four cases of papers which you will find in the President’s private room. The portrait I am very anxious to save, as it is the only original by Stuart. In all events, don’t let them fall into the hands of the enemy, as their capture would enable them to make a great flourish.”

Although a version of the Lansdowne portrait was bought in 1947 by the Brooklyn Museum for seventy thousand dollars, the full-lengths are dreadful pictures.

The Athenaeum portrait has a cameo-like perfection that shows up well on dollar bills and postage stamps, yet it reveals little of that profound insight into character which is the glory of Stuart’s greatest pictures. Of the three life portraits, critics usually prefer the more rough-hewn and less idealized Vaughan portrait, but even it leaves the serious student of either art or human nature much to wish for.

Stuart himself did not contend that his rendering of Washington was pre-eminent. “Houdon’s bust,” he told his daughter, “came first, and my head next. When I painted him, he had just had a set of false teeth inserted, which accounts for the constrained expression about his mouth and the lower part of his face. Houdon’s bust [done in 1783] did not suffer from this defect.”

Although Stuart’s Washingtons have made his name a national byword, they have done great damage to his artistic reputation. His copies of his Athenaeum portrait, which for patriotic reasons occupies prominent positions in so many museums, are for the most part vastly inferior to the original: some of the faces, indeed, seem hardly human. One main reason therefor is that he kept altering the shape of Washington’s head; at first he made it shorter and squatter than in his original painting; thet he went the other way and turned out a series of heads that were longer and thinner. Finally, his Washingtons were merely superficial sketches of the features he had painted ad nauseum. “Mr. Stuart,” an acquaintance wrote, “told me one day when we were before this original portrait that he could never make a copy of it to satisfy himself, and that at last, having made so many, he worked mechanically and with little interest.”

His daughter remembered that toward the end of his life Stuart dashed off Washingtons at the rate of one every two hours.