Contents

Contents

In this guide, we’ve looked at some of the infantry weapons used by the British and Continental Armies during the American Revolution.

We’ve also explained how these weapons were deployed in battle, and what they were like for soldiers to use.

Muskets

Smoothbore muskets were the most common type of weapon used during the American Revolution.

They were effective to a distance of about 100 yards, and fired a round musket ball, with a diameter (caliber) of about 0.60-0.70 inches. Even at a distance of about 100 yards, muskets were very inaccurate, and were much more effective at close range.

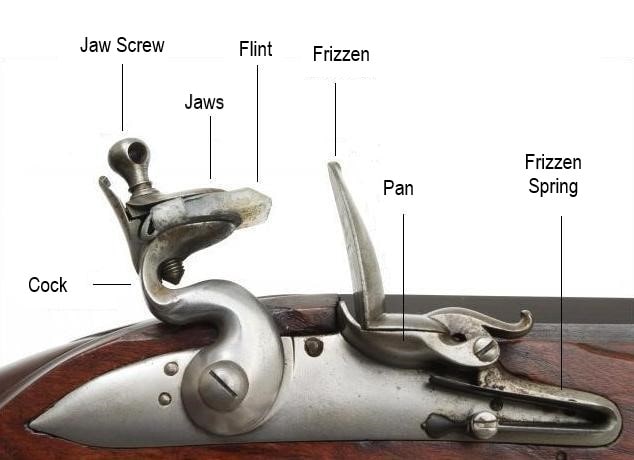

The musket would be loaded with a paper cartridge, which contained gunpowder, and a solid lead ball. The gun would use a flintlock mechanism, where a piece of flint strikes a steel frizzen to create sparks and ignite the gunpowder when the trigger is pulled.

Muskets were slow to load – most skilled soldiers could only fire about three shots per minute. As a result, soldiers spent most of their time fighting using the bayonet affixed to the muzzle of the gun.

Brown Bess

- Used by: Continental and British Armies

- Caliber: 0.75-0.80 (often a smaller musket ball was used for easier reloading)

- Length: 5”

- Barrel length: 0-46.0”

- Effective range: 100 yards

- Origin: Great Britain

The Brown Bess was the most commonly used weapon of the American Revolution, as it was in continual service by large numbers of troops throughout the conflict.

Although it was a British weapon, the Americans made extensive use of captured Brown Besses, especially early in the war. It was heavy, but was relatively quick to reload compared to other muskets of the time.

Charleville musket

- Used by: Continental Army

- Caliber: 0.69 (loaded with a slightly smaller ball)

- Length: 60”

- Barrel length: 45”

- Effective range: 100 yards

- Origin: France

This was an iconic French musket that the Continental Army began using after France entered the war on the American side. It was reliable and easy to maintain, and was well-liked by American soldiers.

Rifles

Continental forces also had long rifles, which were used as a sort of crude sniper rifle for longer-range combat.

They featured a rifled barrel, meaning that there were grooves that would impart spin on the bullet, making it more accurate. Long rifles were accurate to a distance of 200-300 yards, making them much more effective than muskets at long range.

However, the bullet needed to be big enough for the grooves to catch it. This meant that pushing the bullet into the barrel was quite a tight fit, which made reloading a rifle much more difficult than a musket. Depending on the skill of the operator, it was only possible to fire a long rifle one to two times per minute.

Although they were accurate, long rifles were still difficult to fire – they could only be used by trained marksman, using the right technique, and lining up the sights correctly.

Despite this, American forces put the long rifle, also known as the Kentucky rifle, to good use. Colonel Daniel Morgan’s riflemen, also known as Morgan’s Rifles, were an elite infantry force that used long rifles to great effect during the war, including at the Battle of Saratoga.

While the British did use rifles during the Revolutionary War, it was the Americans’ longer-barrelled guns that were used most effectively. While British guns were mass-produced, American rifles were made in smaller quantities based on a German design, and were predominantly made by independent German gunsmiths who had emigrated to the colonies.

Ferguson rifle

- Used by: British Army

- Caliber: 0.65

- Length: 48”, some larger variants also existed

- Barrel length: 32-35”

- Effective range: 300 yards

- Origin: Great Britain

This was one of the best rifles in existence at the end of the 18th century. It was accurate at long distance, and easy to reload. It was one of the first breech-loading rifles used in combat, meaning the operator did not have to reload it by forcing a cartridge down the muzzle.

The British used it at the Battle of Brandywine, but the Ferguson rifle did not see extensive use during the war as it was expensive to manufacture and required more maintenance than most other guns.

Pattern 1776 infantry rifle

- Used by: British Army

- Caliber: 0.63

- Length: 46”

- Barrel length: 5”

- Effective range: 200 yards

- Origin: Great Britain

This was another British rifle, modeled on the Jäger design used by the Germans. It was used by British light infantry and Loyalist units, such as the Queen’s Rangers. About 1,000 were made, and it was a lot more commonly used than the Ferguson rifle, although this gun was not used to as great effect as the American long rifle.

Pistols

Flintlock pistols were also used by some types of soldiers during the Revolutionary War.

They were carried by officers, cavalrymen, and in the navy, where they were used in close-quarters combat when boarding enemy ships.

Pistols worked in much the same way as a musket – they had a flintlock firing mechanism, and were loaded with a 0.50-0.75 caliber lead ball. Due to the shorter barrel, they were only effective at a distance of about 30 yards.

Bayonets, knives, and tomahawks

Revolutionary War battles were often chaotic, and fought in close combat. Due to the ineffectiveness of guns over long distances, and how long they took to reload, a soldier’s edged weapon was often the most important part of his arsenal.

Bayonets were attached to the muzzle of a soldier’s musket, and transformed their gun into a spear for use in close combat. Commanders would often have their units go on a bayonet charge to break through enemy lines.

Officers and cavalrymen often carried swords or sabres, which were symbols of rank, as well as effective weapons in close-quarters combat. On the other hand, frontier forces and Native Americans (who fought on both sides of the war) used tomahawks and knives in battle during the Revolutionary War.

Tomahawks were sort of like a miniature axe, with a light wood handle, and a spike on the opposite side of the blade. Apart from being used in close quarters, they were also thrown in combat, and were used as a versatile tool to skin animals or chop wood at camp.

How did the Continental Army procure weapons?

The Continental Army procured weapons from four primary sources:

- Individual contributions: at the start of the war, colonist militiamen often used their own weapons. These included guns used for hunting or on the farm, as well as leftover weapons from the French and Indian War.

- Captured weapons: even before the American Revolution officially began, rebels began stealing weapons and gunpowder from British magazines, for example when Fort Ticonderoga was taken in May 1775. Also, American privateers were able to successfully capture British merchant and Navy vessels once the war began, intercepting valuable shipments of gunpowder, guns, and artillery.

- Domestic production: as the war progressed, the colonies began producing their own weapons, although only in small quantities compared to the British weapon manufacturing industry. Small workshops and factories were set up, and individual gunsmiths were also able to contribute, especially when it came to producing specialized weapons such as long rifles. Despite its relatively small scale, domestic weapons production was critical to the war effort.

- French imports: once the Franco-American alliance became official, French imports of military weapons in large quantities began, including guns such as the French Charleville musket. This partnership was crucially important in keeping the Continental Army supplied with the weapons it needed.

The biggest issue that Washington and his army faced was procuring enough gunpowder for use with the weapons they had available. Gunpowder was not easy to produce – it required potassium nitrate, also known as saltpeter, which was in short supply in the New World.

Fortunately for Washington, the French were willing to send gunpowder to the Americans as early as the middle of 1776, before the alliance was officially signed. Without this aid, it is unlikely the Continental Army would have run out of gunpowder sometime in early 1777, although a concerted effort was made to produce saltpeter on the continent.